On Killing: The Psychological Cost of Learning to Kill in War and Society (31 page)

Read On Killing: The Psychological Cost of Learning to Kill in War and Society Online

Authors: Dave Grossman

Tags: #Military, #war, #killing

But the Vietnam Veterans Memorial and Memorial Day parades in their honor have fortified and cleansed them, and n o w they are finally beginning to find the strength and courage to reunite with long lost brothers and welcome one another home.

The Condemned Veteran

On returning from Vietnam minus my right arm, I was accosted twice . . . by individuals who inquired, "Where did you lose your arm? Vietnam?" I replied, "Yes." The response was "Good. Serves you right."

—James W. Wagenbach

quoted in Bob Greene,

Homecoming

Even more important than parades and monuments are the basic, day-to-day attitudes toward the returning veteran. Lord Moran felt that public support was a key factor in the returning veteran's psychological health. He believed that Britain's failure to provide her World War I and World War II soldiers the support they needed resulted in many psychological problems.

If Lord Moran could detect a lack of concern and acceptance that had a significant impact on the psychological welfare of World War I and World War II veterans in England, h o w much greater was the adverse impact of the Vietnam vet's much more hostile homecoming?

Richard Gabriel describes the experience:

The presence of a Viet Nam veteran in uniform in his home town was often the occasion for glares and slurs. He was not told that W H A T HAVE W E D O N E T O O U R SOLDIERS? 277

he had fought well; nor was he reassured that he had done only what his country and fellow citizens had asked him to do. Instead of reassurance there was often condemnation — baby killer, murderer — until he too began to question what he had done and, ultimately, his sanity. The result was that at least 500,000 — perhaps as many as 1,500,000 — returning Viet Nam veterans suffered some degree of psychiatric debilitation, called Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, an illness which has become associated in the public mind with an entire generation of soldiers sent to war in Vietnam.

As a result of this, Gabriel concludes that Vietnam produced more psychiatric casualties than any other war in American history.

Numerous psychological studies have found that the social support system — or lack thereof— upon returning from combat is a critical factor in the veteran's psychological health. Indeed, social support after war has been demonstrated in a large body of research (by psychiatrists, military psychologists, Veterans Administration mental-health professionals, and sociologists) to be more crucial than even the intensity of combat experienced.7 W h e n the Vietnam War began to become unpopular the soldiers w h o were fighting that war began to pay a psychological price for it, even before they returned home.

Psychiatric casualties increase greatly when the soldier feels isolated, and psychological and social isolation from home and society was one of the results of the growing antiwar sentiment in the United States. O n e manifestation of this isolation, noted by numero us authors such as Gabriel, was an increase in Dear John letters.

As the war became more and more unpopular back home, it became increasingly common for girlfriends, fiancees, and even wives to dump the soldiers w h o depended upon them. Their letters were an umbilical cord to the sanity and decency that they believed they were fighting for. And a significant increase in such letters as well as many other forms of psychological and social isolation probably account for much of the tremendous increase in psychiatric casualties suffered late in that war. According to Gabriel, early in the war evacuations for psychiatric conditions reached only 6

percent of total medical evacuations, but by 1971, the percentage 278

KILLING IN V I E T N A M

represented by psychiatric casualties had increased to 50 percent.

These psychiatric casualty ratings were similar to home-front approval ratings for the war, and an argument can be made that psychiatric casualties can be impacted by public disapproval.

T h e greatest indignity heaped upon the soldier waited for him when he returned home. Often veterans were verbally abused and physically attacked or even spit upon. T h e phenomenon of returning soldiers being spit on deserves special attention here.

Many Americans do not believe (or do not want to believe) that such events ever occurred. Bob Greene, a syndicated newspaper columnist, was one of those w h o believed these accounts were probably a myth. Greene issued a request in his column for anyone w h o had actually experienced such an event to write in and tell of it. He received more than a thousand letters in response, collected in his book,

Homecoming.

A typical account is that of Douglas Detmer:

I was spat upon in the San Francisco airport. . . . The man who spat on me ran up to me from my left rear, spat, and turned to face me. The spittle hit me on my left shoulder and on my few military decorations above my left breast pockets. He then shouted at me that I was a "mother f ing murderer." I was quite shocked and just stared at him. . . .

That combat veterans returning from months of warfare should accept such acts without violence is an indication of their emotional state. They were euphoric over finally returning home alive; many were exhausted after days of travel, shell-shocked, confused, dehy-drated, and emaciated from months in the bush, in culture shock after months in an alien land, under orders not to do anything to

"disgrace the uniform," and deeply worried about missing flights.

Isolated and alone, the returning veterans in this condition were sought out and humiliated by war protesters w h o had learned from experience of the vulnerability of these men.

T h e accusations of their tormentors always revolved around the act of killing. W h e n those w h o had in any way participated in killing activities were called baby killers and murderers, the result was often deep traumatization and scarring as a result of the hostile WHAT HAVE WE DONE TO O U R SOLDIERS? 279

and accusing "homecoming" from the nation for which they had suffered and sacrificed. And this was the only homecoming they were to receive. At worst: open hostility and spittle. Or at best, as one put it in his letter to Greene, an "indifference that verged on insouciance."

At some level every psychologically healthy human being who has engaged in or supported killing activities believes that his action was "wrong" and "bad," and he must spend years rationalizing and accepting his actions. Many of the veterans who wrote to Greene stated that their letter to him was the first time they had

ever

spoken about the incident to anyone. These returning veterans had shamefully and silently accepted the accusations of their fellow citizens. They had broken the ultimate taboo, they had killed, and at some level they felt that they deserved to be spit upon and punished. When they were publicly insulted and humiliated the trauma was magnified and reinforced by the soldier's own impotent acceptance of these events. And these acts, combined with their acceptance of them, became the confirmation of their deepest fears and guilt.

In the Vietnam veterans manifesting PTSD (and probably in many who don't exhibit PTSD symptoms) the rationalization and acceptance process appears to have failed and is replaced with denial. The typical veteran of past wars, when asked "Did it bother you?" would answer, as a veteran did to Havighurst after World War II, "Hell yes. . . . You can't go through that without being influenced." The Vietnam veteran's defensive response to a nation accusing him of being a baby killer and murderer is consistently, as it was to Mantell and has been so many times to me, "No, it never really bothered me. . . . You get used to it." This defensive repression and denial of emotions appear to have been one of the major causes of post-traumatic stress disorder.

An Agony of Many Blows

American veterans of past wars have encountered all of these factors at one time or another, but never in American history has the combination of psychological blows inflicted upon a group of returning warriors been so intense. The soldiers of the Confederacy 280

KILLING IN V I E T N A M

lost their war, but upon their return they were generally greeted and supported warmly by those for w h o m they had fought. Korean War veterans had no memorials and precious few parades, but they fought an invading army, not an insurgency, and they left behind them the free, healthy, thriving, and grateful nation of South Korea as their legacy. No one spat on them or called them murderers or baby killers when they returned. Only the veterans of Vietnam have endured a concerted, organized, psychological attack by their own people. Douglas Detmer shows remarkable insight into the organization and scope of this attack: Opponents of the war used every means available to them to make the war effort ineffective. This was partially accomplished by usurping many of the traditional symbols of war and claiming them as their own. Among these were the two-fingered V-for-victory sign, which was claimed as a peace symbol; headlights on Memorial Day used as a call for ending the war, rather than denoting the memory of a lost loved one; utilizing old uniforms as anti-war attire, instead of proud symbols of prior service; legitimate deeds of valor denounced as bully-like acts of murder; and the welcome-home parade replaced with what I experienced.

Never in American history, perhaps never in all the history of Western civilization, has an army suffered such an agony of many blows from its own people. And today we reap the legacy of those blows.

Chapter Three

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

and the Cost of Killing in Vietnam

The Legacy of Vietnam: Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

Before a presentation to the leadership of New York's Jewish War Veterans, in a grand old hotel up in the Catskills, over a bowl of borscht, I met Claire, a woman who knew the meaning of PTSD.

She had been a nurse in Burma during World War II and had seen more human suffering than any person should. It had never really bothered her, but when the Gulf War started, she began to have nightmares. Nightmares of an endless stream of torn and mangled bodies. She was suffering from PTSD. A mild case, but PTSD nonetheless.

After another presentation in New York, a veteran's wife asked me to talk with her and her husband. At Anzio he had won the Distinguished Service Cross, our nation's second-highest award for valor, and he continued to fight throughout World War II.

Five years ago he retired. Now all he will do is sit around the house and watch war movies, and he is obsessed with the idea that he is a coward. He is suffering from PTSD.

Post-traumatic stress disorder has always been with us, but the long delay time and the erratic nature of its occurrence has made 282 KILLING IN V I E T N A M

us like the ancient Celts w h o did not understand the link between sex and pregnancy.

What Is PTSD?

Vietnam was an American nightmare that hasn't yet ended for veterans of the war. In the rush to forget the debacle that became our longest war, America found it necessary to conjure up a scapegoat and transferred the heavy burden of blame onto the shoulders of the Vietnam veteran. It's been a crushing weight for them to carry. Rejected by the nation that sent them off to war, the veterans have been plagued with guilt and resentment which has created an identity crisis unknown to veterans of previous wars.

— D. Andrade

Post-traumatic stress disorder is described by the American Psychological Association's

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

as "a reaction to a psychologically traumatic event outside the range of normal experience." Manifestations of P T S D include recurrent and intrusive dreams and recollections of the experience, emotional blunting, social withdrawal, exceptional difficulty or reluctance in initiating or maintaining intimate relationships, and sleep disturbances. These symptoms can in turn lead to serious difficulties in readjusting to civilian life, resulting in alcoholism, divorce, and unemployment. T h e symptoms persist for months or years after the trauma, often emerging after a long delay.

Estimates of the number of Vietnam veterans suffering from PTSD range from the Disabled American Veterans figure of 500,000 to Harris and Associates 1980 estimate of 1.5 million, or somewhere between 18 and 54 percent of the 2.8 million military personnel w h o served in Vietnam.

H o w D o e s P T S D Relate to Killing?

Societies which ask men to fight on their behalf should be aware of what the consequences of their actions may so easily be.

— Richard Holmes

Acts of War

POST-TRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDER

283

Relationship Between Degree of Trauma and Degree of Social Support in PTSD Cau-In 1988, a major study by Jeanne and Steven Stellman at Columbia University examined the relationship between PTSD manifestations and a soldier's involvement in the killing process. This study of 6,810 randomly selected veterans is the first in which combat levels have been quantified. Stellman and Stellman found that the victims of PTSD are almost solely veterans who participated in high-intensity combat situations. These veterans suffer far higher incidence of divorce, marital problems, tranquilizer use, alcoholism, joblessness, heart disease, high blood pressure, and ulcers.

As far as PTSD symptoms are concerned, soldiers who were in noncombat situations in Vietnam were found to be statistically indistinguishable from those who spent their entire enlistment in the United States.

During the Vietnam era millions of American adolescents were conditioned to engage in an act against which they had a powerful resistance. This conditioning is a necessary part of allowing a soldier 284

KILLING IN V I E T N A M

to succeed and survive in the environment where society has placed him. Success in war and national survival may necessitate killing enemy soldiers in battle. If we accept that we need an army, then we must accept that it has to be as capable of surviving as we can make it. But if society prepares a soldier to overcome his resistance to killing and places him in an environment in which he will kill, then that society has an obligation to deal forthrightly, intelligently, and morally with the psychological event and its repercussions upon the soldier and the society. Largely through an ignorance of the processes and implications involved, this has not happened with the Vietnam veteran.

P T S D and Non-killers: Accessory to Murder?

After I had presented the essence of the hypotheses in this book to the leadership of a state Vietnam Veterans Coalition, one of the vets said to me, "Your premise [the trauma of killing, enabled by conditioning, and amplified by society's "homecoming"] is valid not only for those w h o killed, but for those who supported the killing."

This was the state's Veteran of the Year, a lawyer named Dave, w h o was an articulate, dynamic leader within the organization.

" T h e truck driver w h o drove the ammo u p , " he explained, "also drove dead bodies back. There is no definitive distinction between the guy pulling the trigger, and the guy w h o supported him in Vietnam."

"And," said another veteran, almost whispering, "society didn't make any distinction in w h o they spat on."

"And," continued Dave, "just like . . . if you came in this room and attacked one of us you would be attacking all of u s . . . society, this nation, attacked every one of us."

His point is valid. Everyone in that room understood that he was not talking about the veterans of noncombat situations in Vietnam who, according to Stellman and Stellman, were found to be statistically indistinguishable from those w h o spent their entire enlistment in the United States.

Dave was referring to the veterans w h o participated in high-intensity combat situations. They may not have killed, but they POST-TRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDER

285

were there in the midst of the killing, and they were confronted daily with the results of their contributions to the war.

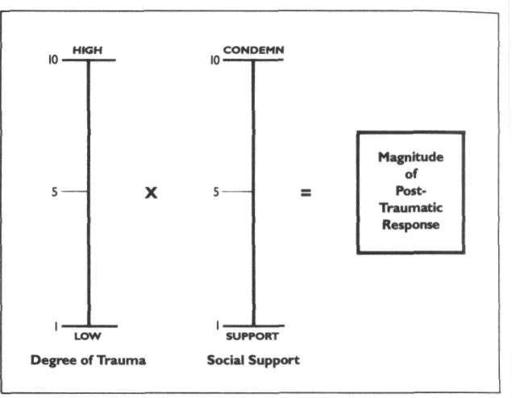

In study after study two factors show up again and again as critical to the magnitude of the post-traumatic response. First and most obvious is the intensity of the initial trauma. The second and less obvious but absolutely vital factor is the nature of the social support structure available to the traumatized individual. In rapes, we have come to understand the magnitude of the trauma inflicted upon the victim by the defense tactic of accusing the victim during trials and have taken legal steps to prevent and constrain such attacks upon the victim by a defendant's attorneys. In combat, the relationship between the nature of the trauma and the nature of the social support structure is the same.

PTSD in the World War II Veteran

The degree of trauma and the degree of social support work together to amplify each other in a kind of multiplicative relationship. For instance, let us take two hypothetical World War II veterans. One of them was a twenty-three-year-old infantryman who saw extensive combat, killed enemy soldiers at close range, and held his buddy in his arms as he died from close-range enemy small-arms fire. The trauma he endured would probably rate at the very top of the degree-of-trauma scale.

Our other World War II veteran was a twenty-five-year-old truck driver (he might just as easily have been an artilleryman, an airplane mechanic, or a bos'n's mate on a navy supply ship) who served honorably, but never really got up to the front lines. Although he was in an area that took some incoming artillery (or bombing or torpedoes) on a few occasions, he never was even in a situation where it was expected that he would have to shoot at anyone, and no one ever really shot at him. But he did have someone he knew killed by that artillery fire (or bombs or torpedoes), and he did see the constant remains of death and carnage as he moved along behind the advancing Allied lines. He would be placed very low on our degree-of-trauma scale.

When our hypothetical World War II veterans came home after the war they returned as a unit together with the same guys they 286 KILLING IN VIETNAM

had spent the whole war with, on board a ship, spending weeks joking, laughing, gambling, and telling tall tales as they cooled down and depressurized in what psychologists would call a very supportive group-therapy environment on the long voyage home.

And if they had doubts about what they'd done, or fears about the future, they had a sympathetic group to talk to. Jim Goodwin notes in his book how resort hotels were taken over and made into redistribution stations to which these veterans brought their wives and devoted two weeks to reacquainting themselves with their family on the best possible terms, in an environment in which they were still surrounded by the company of their fellow veterans.

Goodwin also observes that the civilian population they were returning to had been prepared to help and understand the returning veteran through movies such as

The Man in the Gray Flannel

Suit, The Best Years of Our Lives,

and

Pride of the Marines.

They were victorious, they were justifiably proud of themselves, and their nation was proud of them and let them know it.

Our infantryman was one of the comparatively few World War II vets who participated in a ticker-tape parade in New York.

Everyone griped about how what they really wanted to do was put all this "Army BS" behind them, but he would privately admit that marching in front of those tens of thousands of cheering v civilians was one of the high points of his life, and today even just the remembrance of it tends to make his chest swell a little with pride.

Our truck driver, like the majority of returning vets, did not participate in a ticker-tape parade, but he would probably say that it made him feel good to know that vets were being honored.

And next Memorial Day he did march in his hometown parade as part of the American Legion's commemoration ceremonies. No one was making him do it, but he did it anyway because, well damn it, because he felt like it, and he would keep on doing it every year just like the World War I vets in his town had done as he was growing up.

Both our veterans generally stayed in touch with their World War II buddies, and they linked up with their old comrades in reunions and informal get-togethers. And that was nice, but what was really best about being a veteran was being able to hold POST-TRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDER 287

your head high and knowing just how much your family, friends, community, and nation respected you and were proud of you.

The GI Bill was passed, and if some politician or bureaucrat or organization didn't give the vet the respect he deserved, well, buddy, they would have to answer to the influence and votes of the American Legion and the VFW, who would make damn sure you got treated right.

On our social-support scale, social support provided to these two veterans can be rated as very supportive. Not all returning World War II vets got this kind of support, and it was no bed of roses to return from combat under the best of circumstances, but their nation generally did the best for them that it could.

Remember that the relationship between the degree-of-trauma scale and the social-support scale is multiplicative. These two factors amplify each other. For our infantryman that means that his highly traumatic experience was largely (but perhaps not completely) negated by the very supportive social structure he returned to.

Our truck driver, suffering very little trauma and having received a great deal of support, will probably be able to deal with his combat experiences. Our infantryman may tend to medicate himself pretty regularly down at the bar at the American Legion, but like most veterans he will probably continue to function and lead a perfectly healthy life.

PTSD in the Vietnam Veteran

Now let us consider two hypothetical Vietnam veterans, an eighteen-year-old infantryman and a nineteen-year-old truck driver.

The infantryman arrived at the combat zone, like most every other soldier in Vietnam, as an individual replacement who didn't know a soul in his unit. Eventually he engaged in extensive close combat.

He killed several enemy soldiers, but the hard part was that they were wearing civilian clothes, and one of them, well, damn, he was just a kid, couldn't have been more than twelve. And he had his best buddy die in his arms during a firefight. The trauma he endured definitely rates at the top end of the scale. Maybe fighting kids in civilian clothes, with no rear lines and no chance to ever really rest and get away from the battle, maybe that makes the trauma he endured greater than that of the World War II vet, but 288