Omelette and a Glass of Wine (28 page)

Read Omelette and a Glass of Wine Online

Authors: Elizabeth David

Tags: #Cookbooks; Food & Wine, #Cooking Education & Reference, #Essays, #Regional & International, #European, #History, #Military, #Gastronomy, #Meals

And there were the baskets of fruit, perfect small melons, late plums, under-ripe medlars waiting to soften, peaches, pears hollowed out by a bird or a wasp, figs that had fallen of their own accord, all the fruits of September naturally ripe and sometimes still warm from the sun. Everything in profusion. It is no doubt the remembrance of these early days which makes me despise and dislike all primeurs, the fruit artificially grown, gathered too early and expensively sent, wrapped in cotton wool, to ‘smart’ restaurants.

The garden could hardly be called a garden; it was large, wild and not too well kept. There were fruit trees amongst the flowers, here a pear tree, there a currant bush, so that one could either smell a rose, crush a verbena, or eat a fruit; there were borders of box, but also of sorrel and chibol; and the stiff battalion of leeks, shallots, and garlic, the delicate pale-green foliage of the carrot, the aggressive steel-grey leaves of the artichokes, the rows of lettuce which always ran to seed too quickly.

Wine and Food

, Spring 1965

1.

Flammarion 1927: an English translation of this marvellous cookery book was planned ca. 1965 but did not come to fruition.

2.

Cassell, London, 1963, Knopf, New York, 1961.

1.

Heinemann, 1937.

1.

Cassels.

2.

Home and Van Thal, 1948.

Pomiane, Master of the Unsacrosanct

‘Art demands an impeccable technique; science a little understanding.’ Today the mention of art in connection with cookery is taken for pretension. Science and cookery make a combination even more suspect. Because he was a scientist by profession, making no claims to being an artist, Docteur de Pomiane’s observation was a statement of belief, made in all humility. Vainglory is totally missing from de Pomiane’s work. He knew that the attainment of impeccable technique meant a lifetime – in de Pomiane’s case an exceptionally long one – of experiment and discipline. Out of it all he appears to have extracted, and given, an uncommon amount of pleasure.

Docteur Edouard de Pomiane’s real name was Edouard Pozerski. He was of purely Polish origin, the son of emigrés who had fled Poland and settled in Paris after the Revolution of 1863. Born and brought up in Montmartre, he was educated at the Ecole Polonaise – an establishment described by Henri Babinski, another celebrated Franco-Polish cookery writer, as one of ferocious austerity – and subsequently at the Lycée Condorcet. Pomiane chose for his career the study of biology, specialising in food chemistry and dietetics. Before long he had invented a new science called Gastrotechnology, which he defined simply as the scientific explanation of accepted principles of cookery. For a half-century – interrupted only by his war service from 1914 to 1918 – de Pomiane also made cookery and cookery writing his hobby and second profession. After his retirement from the Institut Pasteur, where he lectured for some 50 years, he devoted himself entirely to his cookery studies. He was 89 when he died in January 1964.

De Pomiane’s output was immense – some dozen cookery books, countless scores of articles, broadcasts, lectures. In France his books were best-sellers; among French cookery writers his place is one very much apart.

Many before him had attempted to explain cookery in scientific terms and had succeeded only in turning both science and cookery into the deadliest of bores.

De Pomiane was the first writer to propound such happenings as the fusion of egg yolks and olive oil in a mayonnaise, the sizzling of a potato chip when plunged into fat for deep-frying, in language so

straightforward, so graphic, that even the least scientifically minded could grasp the principles instead of simply learning the rules. In cooking, the possibility of muffing a dish is always with us. Nobody can eliminate that. What de Pomiane did by explaining the cause, was to banish the

fear

of failure.

Adored by his public and his pupils, feared by the phoney, derided by the reactionary, de Pomiane’s irreverent attitude to established tradition, his independence of mind backed up by scientific training, earned him the reputation of being something of a Candide, a provocative rebel disturbing the grave conclaves of French gastronomes, questioning the holy rites of the ‘white-vestured officiating priests’ of classical French cookery. It was understandable that not all his colleagues appreciated de Pomiane’s particular brand of irony:

‘As to the fish, everyone agrees that it must be served between the soup and the meat. The sacred position of the fish before the meat course implies that one must eat fish

and

meat. Now such a meal, as any dietician will tell you, is far too rich in nitrogenous substances, since fish has just as much assimilable albumen as meat, and contains a great deal more phosphorus …’ Good for Dr de Pomiane. Too bad for us that so few of his readers – or listeners – paid attention to his liberating words.

It does, on any count, seem extraordinary that thirty years after de Pomiane’s heyday, the dispiriting progress from soup to fish, from fish to meat and on, remorselessly on, to salad, cheese, a piece of pastry, a crème caramel or an ice cream, still constitutes the standard menu throughout the entire French-influenced world of hotels and catering establishments.

Reading some of de Pomiane’s neat menus (from

365 Menus, 365 Recettes

, Albin Michel 1938) it is so easy to see how little effort is required to transform the dull, overcharged, stereotyped meal into one with a fresh emphasis and a proper balance:

Tomates à la crème

Côtelettes de porc

Purée de farine de marrons

Salade de mâche à la betterave

Poires

An unambitious enough menu – and what a delicious surprise it would be to encounter such a meal at any one of those country town

Hôtels des Voyageurs, du Commerce, du Lion d’Or, to which my own business affairs in France now take me. In these establishments, where one stays because there is no choice, the food is of a mediocrity, a predictability redeemed for me only by the good bread, the fresh eggs in the omelettes, the still relatively civilised presentation – which in Paris is becoming rare – the soup brought to table in a tureen, the hors d’œuvre on the familiar, plain little white dishes, the salad in a simple glass bowl. If it all tasted as beguiling as it looks, every dish would be a feast. Two courses out of the whole menu would be more than enough.

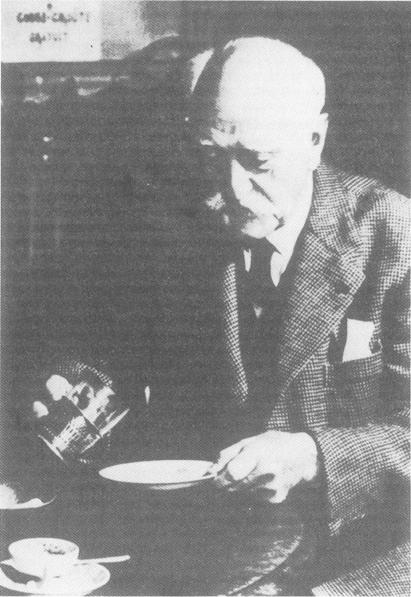

Edouard de Pomiane, courtesy of Bruno Cassirer (Publishers) Ltd

Now that little meal of de Pomiane’s is a feast, as a whole entity. It is also a real lesson in how to avoid the obvious without being freakish, how to start with the stimulus of a hot vegetable dish, how to vary the eternal purée of potatoes with your meat (lacking chestnut flour we could try instead a purée of lentils or split peas), how to follow it with a fresh, bright, unexpected salad (that excellent mixture of corn salad and beetroot – how often does one meet with it nowadays?) and since by that time most people would have had enough without embarking on cheese, de Pomiane is brave enough to leave it out. How much harm has that tyrannical maxim of Brillat Savarin’s about a meal without cheese done to all our waistlines and our digestions?

For a hot first dish, de Pomiane’s recipe for

tomates à la crème

is worth knowing. His method makes tomatoes taste so startingly unlike any other dish of cooked tomatoes that any restaurateur who put it on his menu would, in all probability, soon find it listed in the guide books as a regional speciality. De Pomiane himself said the recipe came from his Polish mother. That would not prevent anyone from calling it what he pleases:

TOMATES À LA CRÈME

‘Take six tomatoes. Cut them in halves. In your frying pan melt a lump of butter. Put in the tomatoes, cut side downwards, with a sharply-pointed knife puncturing here and there the rounded sides of the tomatoes. Let them heat for five minutes. Turn them over. Cook them for another ten minutes. Turn them again. The juices run out and spread into the pan. Once more turn the tomatoes cut side upwards. Around them put 80 grammes (3 oz. near enough) of thick cream. Mix it with the juices. As soon as it bubbles, slip the tomatoes and all their sauce on to a hot dish. Serve instantly, very hot.’

The faults of the orthodox menu were by no means the only facet of so-called classic French cooking upon which de Pomiane turned his analytical intelligence. Recipes accepted as great and sacrosanct are not always compatible with sense. Dr de Pomiane’s radar eye saw through them: ‘

Homard à l’américaine

is a cacophony … it offends a basic principle of taste.’ I rather wish he had gone to work on some of the astonishing things Escoffier and his contemporaries did to fruit. Choice pears masked with chocolate sauce and cream, beautiful fresh peaches smothered in raspberry purée and set around with vanilla ice seem to me offences to nature, let alone to art or basic principles. How very rum that people still write of these inventions with breathless awe.

De Pomiane, however, was a man too civilised, too subtle, to labour his points. He passes speedily from the absurdities of haute cuisine to the shortcomings of folk cookery, and deals a swift right and left to those writers whose reverent genuflections before the glory and wonder of every least piece of peasant cookery-lore make much journalistic cookery writing so tedious. By the simple device of warning his readers to expect the worst, de Pomiane gets his message across. From a village baker-woman of venerable age, he obtains an ancestral recipe for a cherry tart made on a basis of butter-enriched bread dough. He passes on the recipe, modified to suit himself, and carrying with it the characteristically deflating note:

‘When you open the oven door you will have a shock. It is not a pretty sight. The edges of the tart are slightly burnt and the top layer of cherries blackened in places … It will be received without much enthusiasm for, frankly, it is not too prepossessing.

‘Don’t be discouraged. Cut the first slice and the juice will run out. Now try it. A surprise. The pastry is neither crisp nor soggy, and just tinged with cherry juice. The cherries have kept all their flavour and the juice is not sticky – just pure cherry juice. They had some good ideas in 1865.’

Of a dish from the Swiss mountains, Dr de Pomiane observes that it is ‘a peasant dish, rustic and vigorous. It is not everybody’s taste. But one can improve upon it. Let us get to work.’ This same recipe provides an instructive example of the way in which Dr de Pomiane thinks we should go to work improving a primitive dish to our own taste while preserving its character intact. Enthusiastic beginners might add olives, parsley, red peppers. Dr Pomiane is scarcely that simple. The school-trained professional might be tempted to super-

impose cream, wine, mushrooms, upon his rough and rustic dish. That is not de Pomiane’s way. His way is the way of the artist; of the man who can add one sure touch, one only, and thereby create an effect of the pre-ordained, the inevitable, the entirely right and proper:

TRANCHES AU FROMAGE

‘Black bread – a huge slice weighing 5 to 7 oz., French mustard, 8 oz. Gruyère.

‘The slice of bread should be as big as a dessert plate and nearly 1 inch thick. Spread it with a layer of French mustard and cover the whole surface of the bread with strips of cheese about ½ in. thick. Put the slice of bread on a fireproof dish and under the grill. The cheese softens and turns golden brown. Just before it begins to run, remove the dish and carry it to the table. Sprinkle it with salt and pepper. Cut the slice in four and put it on to four hot plates. Pour out the white wine and taste your cheese slice. In the mountains this would seem delicious. Here it is all wrong. But you can put it right. Over each slice pour some melted butter. A mountaineer from the Valais would be shocked, but my friends are enthusiastic, and that is good enough for me.’

This is the best kind of cookery writing. It is courageous, courteous, adult. It is creative in the true sense of that ill-used word, creative because it invites the reader to use his own critical and inventive faculties, sends him out to make discoveries, form his own opinions, observe things for himself, instead of slavishly accepting what the books tell him. That little trick, for example, of spreading the mustard on the bread

underneath

the cheese in de Pomiane’s Swiss mountain dish is, for those who notice such things, worth a volume of admonition. So is the little tomato recipe quoted above.

All de Pomiane’s vegetable dishes are interesting, freshly observed. He is particularly fond of hot beetroot, recommending it as an accompaniment to roast saddle of hare – a delicious combination. It was especially in his original approach to vegetables and sauces that de Pomiane provoked the criticism of hidebound French professional chefs. Perhaps they were not aware that in this respect de Pomiane was often simply harking back to his Polish origins, thereby refreshing French cookery in the perfectly traditional way.

De Pomiane gives, incidentally, the only way (the non-orthodox way) to braise Belgian endive with success – no water, no blanching, just butter and slow cooking.