Oh, Beautiful: An American Family in the 20th Century

Read Oh, Beautiful: An American Family in the 20th Century Online

Authors: John Paul Godges

OH, BEAUTIFUL

An American Family in the 20th Century

John Paul Godges

Copyright © 2010 John Paul Godges, all rights reserved.

Published in the United States of America

By Amazon DTP, Seattle, Washington

First edition published 2010

Cover design by Eileen La Russo

Oh, Beautiful: An American Family in the 20th Century

is available in trade paperback edition from Amazon.com and from the CreateSpace e-store, in Kindle e-book edition from the Amazon Kindle Store, and in multiple e-book formats from Smashwords, including those available from the Apple iBookstore. The author is not being compensated by any company or service mentioned here in exchange for such mention.

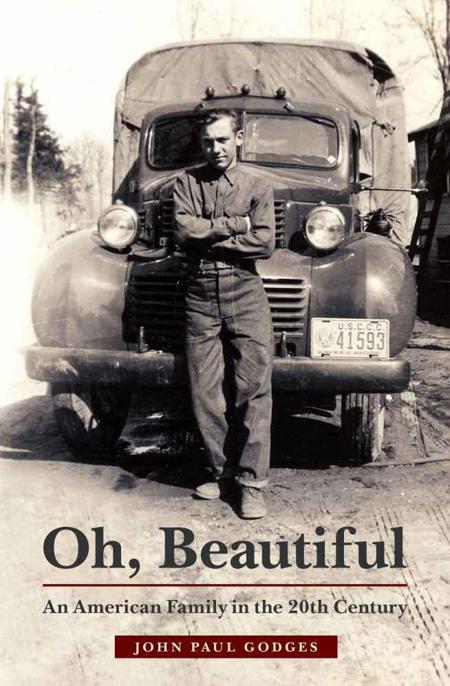

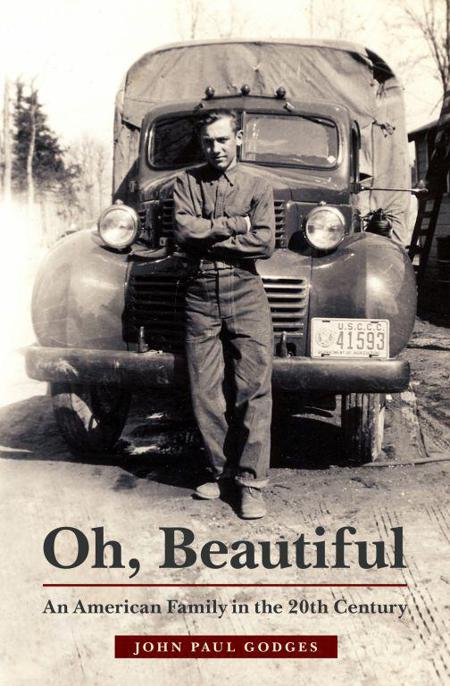

ON THE COVER: In April 1941, Jozef Godzisz, a 17-year-old immigrant from Poland, leans against a Civilian Conservation Corps work truck at Camp Evelyn, located in the Hiawatha National Forest on Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, near the towns of Wetmore and Munising.

In tribute to my father and my mother

and to the worlds from which they came.

In dedication to my nephews—

Jon, Dan, Max, Mark, and Ryan—

and to those who will follow.

To bring out the best in all of us.

CONTENTS

PART THREE: GOING SEPARATE WAYS

PART FOUR: COMING BACK TOGETHER

In 1968 at the age of six, I watched in suspense as my mom and older brothers and sisters launched into a spirited discussion—somewhere between cooking dinner, scrubbing the floor, playing hide-and-seek, doing homework, and practicing the piano—about who took after whom. The discussion was about nationality more than personality.

“

Mary Jo’s still got blond hair,” somebody said, “even though she’s not a baby anymore. That makes her the Polack of the family.”

“

Joe’s got those big Abruzzi hands,” somebody else said. “That makes him a good dago.”

My brothers and sisters were mostly joking around, poking fun at each other’s inherited traits from the old country, and vying to see who would qualify, on balance, as what. But they were also doing two things that struck the kid in me as mighty important: They were defining themselves as individuals, even as they were carving out some sense of place in the family.

I didn’t want to be left out of place. “What am

I

?” shrieked the six-year-old with an identity crisis.

The room fell oddly silent. I found myself becoming the object of a rigorous inspection from 10 to 12 eyeballs gazing down upon me from on high. Hmm. No Roman nose—not yet, at least. Hmm. Nope, no pasty white northern skin, either. Hmm. Can’t detect any Latin passion. Nor any Slavic stoicism. Hmm. Maybe I was still too young, too unformed, to have exhibited any telltale ethnic traits, physical or behavioral.

I can’t recall who broke the silence, but the exasperated response spoke for everyone. “Oh,” someone finally bellowed in mock resignation, “you’re A-me-ri-can!”

Everyone burst into hysterics. They were so proud of themselves, having dodged a tough question and, best of all, having found yet another way to amuse themselves.

But something deeper was also happening at that point in the discussion. There was something almost unheard of in our family: instant unanimity. The clever response about my being an “A-me-ri-can” worked as a sort of armistice, a friendly way to tear down the flimsy familial fences by pointing toward a common future. At least the youngest child in our brood of six—the final legacy of this particular generation—would be exclusively and unambiguously American. For good or naught, the destinies of everyone else in the family—along with their light Polish hair, big Italian hands, and God-only-knew-what other inherited idiosyncrasies—were inextricably tied to that common American destiny.

The discussion ended. It had reached its logical conclusion.

For me, though, the question remained unanswered. Sure, it was deft and comical for somebody to transcend the ethnic divide and to anoint me as an American for lack of a better name. But it was also a cop-out. My family didn’t know

what

to make of me, so they dubbed me an American by default. There was nothing wrong with being an American. In fact, it made the six-year-old kid in me feel kind of special. I was different. That was fun. But I had no idea what it meant to be different as an American.

“

America is the strongest, richest, and most powerful country in the world,” Dad taught us as we were growing up in the 1950s and 1960s.

“

America is a BYOO-tiful country,” Mom echoed the way her own father used to say it.

Dad and Mom knew better than we, their children, ever could. Dad was an immigrant from Poland. Mom was born in America just 11 years after her parents had immigrated from Italy.

“

We have so much to be thankful for,” Dad and Mom harmonized.

We believed them. We counted our blessings. We never doubted our good fortune.

But I couldn’t stop wondering: “What does it mean to be an American?”

I’ve wondered for decades. I studied America in college and wrote about it, then studied it some more and wrote about it some more. The driving motivation has been to understand what makes America tick, what lies at its cultural core, what makes America work, and what could make it work better.

Two momentous national events at the dawn of the 21st century begged the question—“What does it mean to be an American?”—louder than perhaps at any time since the Civil War. The presidential election of 2000 revealed a society so riven with division that neither side won. Then, within a year, the terrorist attacks of 2001 tapped an immense reservoir of unity. Neither the division nor the union negated the other. Both persisted in full force. Neither one by itself sufficiently represented America.

It occurred to me that the meaning of America could never be captured in a single event, frozen in a single snapshot in time, inscribed in a single document, nor embodied in the life of a single individual. Nor could America be defined by a single generation.

Instead, I surmised, the meaning of America is dynamic. If the meaning resides anywhere, it resides somewhere within the story of how Americans themselves, both newcomers and natives, find meaning in their lives in this country. The meaning of the story itself is in constant flux, because the story gets passed down and retold from one generation to the next. Each time that the heirs to the story retell it, they bequeath to their children not just a common identity rooted in the past, which is important, but also a new and unique aspiration geared toward the future, which is even more important.

For these reasons, I believe the best way that I, the son of a Polish immigrant and grandson of Italian immigrants, can fathom the meaning of the American experience is by sharing the story of my own family in America in the 20th century. I harbor no illusions that the story of my family can encapsulate the entire story of America over any period of time. No single nationality, tribe, race, or religious community created this country, and none of them alone can fully reflect it. The geographic, cultural, racial, ethnic, religious, social, and economic diversities of this nation are simply far too immense. Besides, my family is downright quirky at times, as are all families in their own ways. It is a very good thing that the greatness of America extends far beyond the quirkiness of my family.

Nevertheless, it is intriguing how much of the national experience has seeped into the family’s experience. It is compelling how many of the tragedies and triumphs that have occurred at home have occurred in so many other homes. And it is amusing how many of the extremes within the family mirror the extremes within society at large.

Personal fears correlate with national anxieties. Family fights echo social battles. The resolution of family disputes imparts clues to the resolution of social conflicts. And the family’s proudest moments emulate the nation’s finest hours.

This book is not a memoir about me or about my interpretations of things. It is more akin to a

collection

of memoirs—or of

overlapping

interpretations of things—none of which would be as illuminating in the absence of the others. The book is the product of interviews with three generations of family members, the oldest of whom have shared memories of their forefathers and the countries from which they came. To verify facts and to clarify foggy reminiscences, I have relied on genealogical and historical research. By combining oral history with historical investigation in this way, I have tried to portray, as closely as possible, the truth—not just about my family but also about the times and societies in which they have lived.

Most of the time, the story proceeds in a chronological fashion. But Part Three, which is devoted to “going separate ways,” breaks from the norm on purpose. In Part Three, each individual shares his or her own story about self-discovery in America as one link in a chain of chapters that overlap in time. The benefit of this approach is to show how the same historical period can be viewed through multiple different lenses, creating alternative impressions of the meaning of the time. The stories in Part Three appear in sequential order not of the births of the featured individuals but rather of the adult crises that spur the individuals to define their roles within the family and the community.