Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (12 page)

Read Obsessive Compulsive Disorder Online

Authors: Polly Waite

Some young people may be reluctant to recall and discuss anxiety-related cognitions that are related to anticipated danger (Clark and Beck, 1988) and may experience intense emotion as they may fear negative consequences associated with talking about their worries (e.g. that the worry may come true) or that the therapist may think they are bad or crazy. If the young person is hesitant in voicing their obsession, the therapist should gently persist in trying to identify the thought and normalise different kinds of thoughts (including the therapist’s own thoughts) to try to make the young person feel more comfortable. It can also be helpful to try and identify and deal with the young person’s specific worries relating to talking about their obsessions by asking questions such as ‘What upsets you most about talking about these things?’ or ‘In your worst nightmare what could happen if you talk about these things?’ Once the worries have been identified the therapist should help the young person see that their feared predictions are unlikely to come true; for example, by asking them whether something bad has ever happened to them by talking about these things and informing them that it is very rare for ‘bad’ people to get OCD as ‘bad’ people aren’t normally bothered by nasty thoughts.

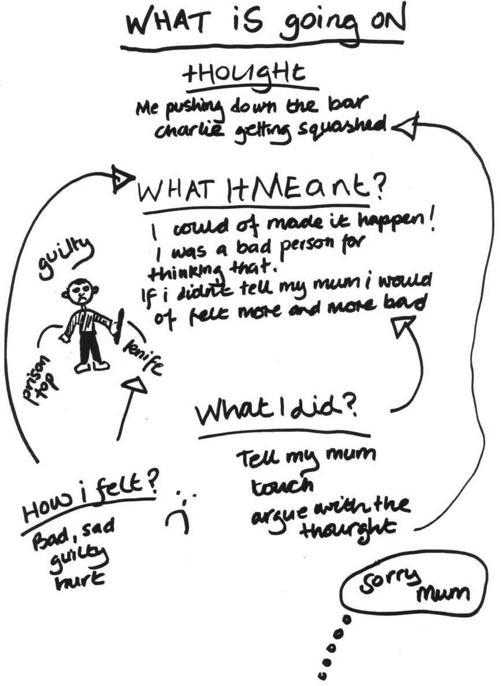

By the end of the discussion, the therapist and young person will have drawn out a shared formulation. Younger children can enjoy drawing it out themselves and they should be encouraged to add pictures or symbols to make the diagram more meaningful. Jack’s formulation (Figure 4.1) illustrates how the problem is working. An intrusive thought pops into his mind and is interpreted as being meaningful (i.e. it could come true unless he does something to stop it and that it means he is a bad brother). This leads him to feel bad, sad, hurt and guilty and as a consequence he carries out a compulsion (touching the climbing frame and saying ‘I love Charlie’ in his head) and other safety behaviours (such as asking for reassurance from his mum and arguing with the thought). However, these behaviours lead him to

58

Waite, Gallop and Atkinson

Figure 4.1

Jack’s formulation

experience more intrusive thoughts and to believe more strongly that the meaning attached to the thoughts is true, thereby maintaining and exacerbating the problem.

Once the formulation has been drawn, the therapist should check with the young person that it is an accurate representation of what went on, make necessary amendments and ask the young person to summarise what has been drawn to check their understanding. The therapist should then ask the young person whether they feel this drawing would make sense for other times when their OCD has been a problem. If the young person feels that this is not the case, it can be helpful to repeat the formulation process for a different episode to highlight the fact that, whatever the situation, OCD

tends to work in the same way.

Planning and carrying out treatment

59

Sometimes it can be hard for the young person to identify a clear intrusion or describe what the intrusion meant to them. They may say things like ‘I can’t think of anything that came into my head or why I felt I should do it, I just felt I had to do it!’ In these cases it can be helpful to try further questioning to help the young person identify the intrusion: for example, ‘What was the first thing you noticed, the first sign that OCD might be around?’ or ‘At that moment what came into your head, did you notice any thoughts or pictures before the problem started?’ If the young person is having difficulties identifying the meaning of the intrusion, the therapist should refer back to any hints that were given during the initial assessment process and in the young person’s answers in the pre-treatment questionnaires. The therapist should also bear in mind the key areas that are thought to be associated with the misinterpretation of normal intrusions in OCD

such as:

• overestimating the likelihood of danger

• fearing causing or not preventing harm

• feeling responsible for causing or preventing harm

• fearing unrealistic consequences of associated anxiety

• fearing that thinking something will make it actually come true.

If with further questioning the young person is still not able to identify the meaning, it can be helpful to proceed by saying that their intrusion felt awful. The therapist can then move on to discussing the compulsion associated with the intrusion and then work backwards by asking ‘In your worst nightmare, what would you have worried might have happened if you had not been able to do the compulsion?’ If necessary, the therapist should help the young person to design an experiment where they refrain from carrying out a compulsion in order to find out the meaning. For example, if the young person neutralises to prevent the occurrence of thoughts the therapist may need to get them to experience the intrusive thought (image or urge) without neutralising and ask them to describe what happens.

• In the first session, the therapist needs to find out what the young person calls or would prefer to call obsessions, compulsions and OCD generally.

• The focus is then on gaining a greater understanding of the problem and this is done by reviewing a recent occasion where OCD was around.

• The therapist and young person then draw out a formulation which shows how the problem is working and being maintained.

60

Waite, Gallop and Atkinson

The vicious cycle of OCD

Once the young person feels that the picture of what happened is complete, the next step is to create doubt within the child about the usefulness of their responses. This is achieved by suggesting the possibility that the things they are doing (such as compulsions or avoidance) are actually making the problem worse as they strengthen the meaning they have attached to their intrusion and do not provide them with the opportunities to discover that their feared consequences do not come true. This in turn means they are more likely to keep doing the compulsions and other unhelpful behaviours. Sometimes the young person may have already reached this conclusion whilst trying to make sense of what happened. For example, they may have commented that they try to push the thought out, but this does not work and the thought comes back stronger and this gives the therapist a way in. However, this is not always the case and can be one of the most difficult parts of the session, as very often the young person has not made sense of the problem in this way before and has been seeing the behaviours as the way of getting rid of the thought and making themselves feel better, not worse. Consequently, the therapist should take whatever time is needed to help the young person understand these feedback processes and may need to use a number of different strategies such as guided discovery, psychoeducation, role play, storytelling and metaphors. It can also be helpful to begin the process of explaining feedback loops and vicious cycles by focusing on the most prominent response strategies (e.g. ritual, avoidance or looking for danger) that the young person identified in the formulation, for example, with Jack:

Therapist:

Okay Jack, I’m a bit confused and I wonder if you can help me. You’ve told me all about this problem with getting horrible thoughts and the things OCD gets you to do to make the problem better and get rid of the thoughts. The bit I’m confused about is that you’ve also told me that over time this problem has got worse and worse rather than getting better.

Is that right?

Jack:

Yes.

Therapist:

So I wonder whether the things OCD has been telling you to do might actually be making the problem worse, even though it tells you that it is going to be making it better. Do you think that could be the case?

Jack:

Maybe?

Therapist:

I wonder if it’s a bit like if a carpenter was using sandpaper on a door that is too big to fit the frame. He keeps using the sandpaper over and over because it seems to be a good idea at first. The problem is he keeps sanding it so much that eventually the door won’t fit because it’s now too small! His solution actually became the problem!

Jack:

I get it, but how is that the same as my OCD?

Planning and carrying out treatment

61

Therapist:

Well let’s have a look. Let’s see how doing habits might be causing part of the problem. Now if I have got this right, you believed in your heart that unless you touched the climbing frame and thought about how you loved Charlie you might have squashed him. Is that right?

Jack:

Yes I know I wouldn’t but I was really worried that I might.

Therapist:

Now when you did the habit and then you didn’t hurt Charlie, what did this make you think?

Jack:

I guess that if I hadn’t done it I might have actually hurt him.

Therapist:

Can you see what the problem with that is? Can you see what you don’t get to find out?

Jack:

I guess that maybe I wouldn’t have done it even if I hadn’t done the habit.

Therapist:

That’s exactly right. I guess you don’t know that anything bad would have happened if you hadn’t carried out the ritual.

You don’t know whether your ritual made any difference at all. I’m going to tell you a little story that I think might help us think about your rituals. . . .

Say there was a man standing in [a place near Jack’s home] with his pockets full of salt. The man is throwing piles of salt everywhere. People think what he is doing looks very strange. Someone goes up to the man and asks, ‘Why are you throwing salt all over the floor?’ and the man replies, ‘To keep the alligators away!!’

What do you make of this story?

Jack:

It’s a bit silly. I mean why would he be throwing salt? You don’t get alligators where I live.

Therapist:

That’s what I think too, but how come the man doesn’t know that?

Jack:

Because he thinks they’re not coming because he’s throwing the salt.

Therapist:

Exactly! What do you think he would have to do to find out what we all know?

Jack:

Stop throwing the salt and wait and see if any come. Perhaps he could hide just in case!

Therapist:

That sounds like a good idea. How might that story relate to your habits?

Jack:

Well I guess I’m like the man throwing the salt, apart from I’m worried about hurting people not alligators!

Therapist:

That’s right, so if you’re similar to the man throwing salt, what do you think you might need to do?

Jack:

Stop doing the habits and see what happens?

Therapist:

That sounds like a really good idea!

This also illustrates the usefulness of metaphors, stories and imagery to help the young person to make sense of what is going on. Chapter 5 provides more examples of metaphors that can be helpful to use with young people.

62

Waite, Gallop and Atkinson

• The formulation is used to think about whether compulsions (and other responses, such as avoidance or seeking reassurance) may actually keep the problem going and act as a vicious cycle.

• This can be difficult and so the therapist may need to use a range of different strategies including guided discovery, psychoeducation, role play, storytelling and metaphors.

Psychoeducation

Early on in therapy, the therapist also picks up on some ‘basic facts’ of OCD

that start to help the young person to think differently about their OCD.

As discussed in Chapter 1, there is good evidence that most of the population have intrusive thoughts. This information is critical in starting to think about the problem in a different way. It can be helpful to ask the young person and their family to begin by estimating what percentage of the population have intrusive thoughts, pictures or doubts and then let them know that in fact about 90 per cent of the population report having them. The therapist can use this as an opportunity to challenge any beliefs that the young person may have had about themselves (e.g. that they were going mad or are a bad person) and enable them to see that actually these thoughts meant that they were normal. The therapist may also let the young person know that thoughts tend to be about things that are meaningful or important to us. For example, Jack’s thought of harming people he loves came along when his younger brother Charlie was born and there was an understandable feeling of sibling rivalry, but at the same time a worry about hurting his new brother given he was so small and vulnerable.

Once the young person accepts that it is normal to have intrusive thoughts, they may still feel that they could solve the problem if they could get control of them or even get rid of them completely. It can be helpful to use a behavioural experiment at this point to demonstrate that it is not possible to control your thoughts. The therapist may have the child and family try not to think of a pink giraffe to demonstrate that when they try not to think about something it inevitably pops into their mind. It can also be helpful to have a discussion about what life would be like if you never had a thought coming into your mind uninvited and that we need thoughts to pop into our heads in order to be creative human beings.