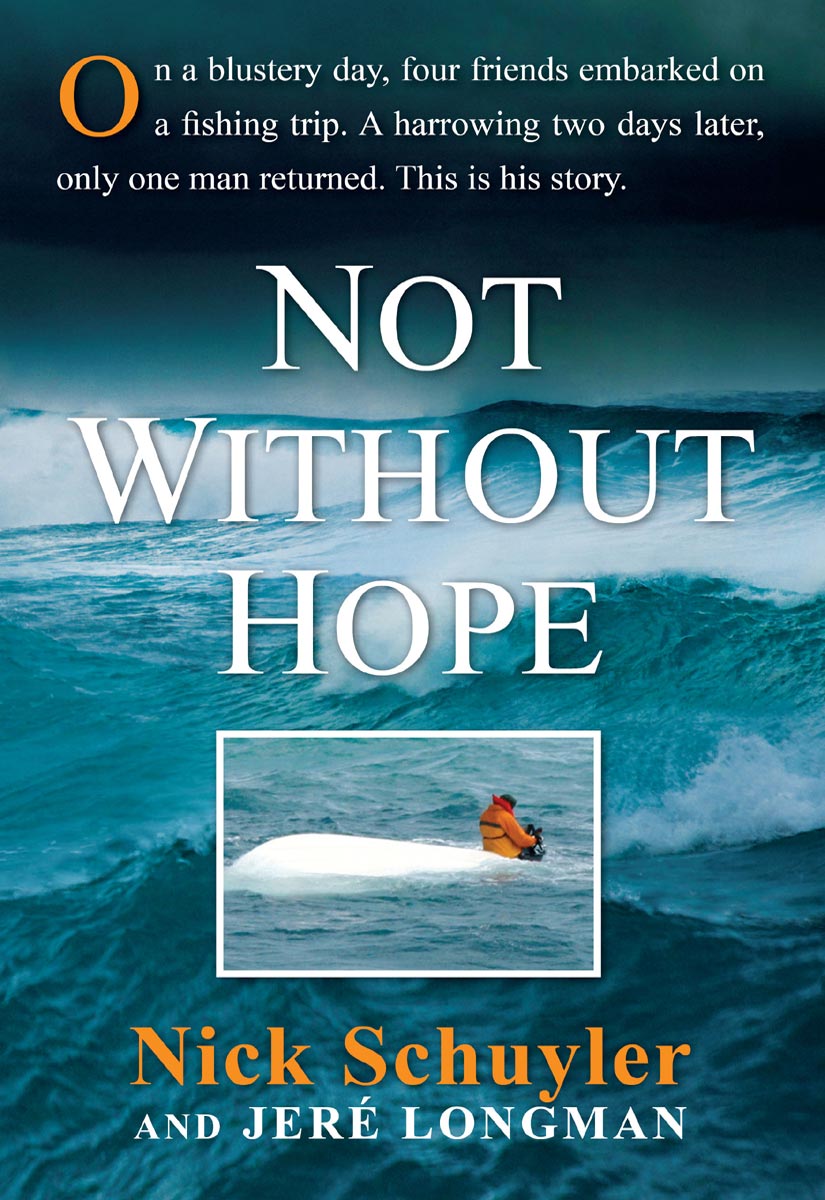

Not Without Hope

Authors: Nick Schuyler and Jeré Longman

Nick Schuyler and Jeré Longman

In memoriam:

Will Bleakley

Marquis Cooper

Corey Smith

I could not have my mother come to my funeral.

The first few days home from the hospital, I got…

I

could not have my mother come to my funeral. A year later, that is the best explanation I can give. Four of us went into the water, and I was the only one who came out. Why me? My friends were just as big and strong and tough and brave. Two of them, Marquis Cooper and Corey Smith, played in the National Football League. Will Bleakley, my best friend, had been a tight end in college. We were young and athletic, and athletes grow to feel invincible. Yet I was the only one pulled from the Gulf of Mexico when our boat capsized. Why did I make it when they did not? It haunts me.

I think about that day, those horrible hours, all the time. The littlest thing puts me back out there: a stray thought, a glimpse of open water, a look from a stranger that says, “Aren’t you that guy?” The accident trails me like the wake of Marquis’s boat, churning, foaming, pushing toward the horizon of every day. Why me? Why did I make it when they did not? Science might have an answer in warm air trapped against the skin and sustained core body temperature, but that is a cold, clinical explanation. The only answer I

have is my mother. I could not bear for her to see me in a casket, her twenty-four-year-old son laid out in waxy eternity—or even worse, lost forever at sea.

I am no hero. Maybe if I had brought my friends back with me. At least one of them…or all of them. But I didn’t. I tried; I gave it everything I had, but I couldn’t. I’m only a survivor. I was not particularly interested in telling my story. But I knew that someone would, and it might as well be me. I could deal in fact, not rumor. I could let the families of Marquis and Corey and Will know the truth of what happened. I could dispel the misinformation that we were horsing around and fighting and getting drunk. I could dismiss the ridiculous notion that they gave up or that I harmed them or ignored them to save myself. There is so much crazy stuff out there—I even heard somewhere that we were captured by pirates. In the end, I decided to write this book. It is cathartic to tell the story, though really that’s the least of it. For the other families, I wanted the story to be told the right way, not so much for me but for them. And who knows? Maybe this story will help others avoid the mistakes we made.

This is the way I remember it. If I get some things wrong, it is due to the frailties of memory and the horror of what I experienced, not any intention to amend or deceive. This is what I recall after being in the water for forty-three hours, frigid and aching and scared, so hungry and thirsty that I felt I was eating my teeth. This is the best I can do after having three friends die, two of them in my arms. The saddest thing about this story is, I am the only one left to tell it.

T

he sun was not yet up when we put into the water on February 28, 2009. It was about six thirty on a Saturday morning, and nearly a dozen boats had already launched from the Seminole Boat Ramp in Clearwater, Florida. Their lights shined green and red. Residential towers lined the Intracoastal Waterway. A few hundred yards ahead stood the Causeway Bridge that separated downtown Clearwater from Clearwater Beach. There was wind in the palm trees at the boat launch. Sometimes a gust seemed to brush the shallow water like suede. A cold front was expected to blow through later in the day.

Clearwater, located west of Tampa on Florida’s Gulf Coast, is the home of the original Hooters. Says so right on the building. It is also the spring training base of the Philadelphia Phillies, who had won the World Series a few months earlier. Players had reported to camp for another expectant season, but there was still a chill in the air in late winter. We were bundled up in jackets and hats and windbreakers and wind pants. I ran my hand through the water, and it felt cold. Don’t worry, Marquis said. It would warm up by the time we stopped to catch our bait fish.

We were headed about sixty-five or seventy miles west of Clearwater Pass to a shipwreck site that was one of Marquis’s favorite fishing areas. In a week, he was leaving town for an off-season training camp with the Oakland Raiders. He had sold his house and was closing in a few days. Most of his furniture was already out. He was scheduled to fly to Seattle, where he had attended the University of Washington. He would pick up a car and drive down to Oakland for minicamp. This fishing trip was a going-away celebration. Marquis planned to keep a residence in the Tampa area, but he wasn’t sure if he would get another chance to fish before football season started. He loved being on the water. He spent all his free time with his family or his boat. He had met his wife, Rebekah, at Washington. They had a three-year-old daughter, Delaney. He called her Goose.

Marquis was twenty-six, and had been drafted by Tampa Bay in the third round of the 2004 NFL draft. He had played for six teams, including three stints with the Pittsburgh Steelers. He was undersized for a linebacker at 6 feet 3 inches, 215 pounds. But Marquis was a freak of nature—the strongest pound-for-pound guy I have ever seen. Maybe 6 percent body fat. Absolutely shredded, ripped. Skinny waist, real skinny torso, giant shoulders and back. He looked like he weighed 230 because he was so thin and so wide.

Marquis was cool, calm, and collected. He stuttered a bit, but he had a swagger about him. Real nice guy. We met at an L.A. Fitness where I worked as a personal trainer in Lutz, Florida, just north of Tampa. You could tell he was somebody special, not just another guy working out. We got close around New Year’s of 2009. I saw how he worked out and how good a shape he was in. I would give him a hard time. I told him I could push him, get him to another level.

“You need to start working with me,” I told him.

Sure, why not? he said. He was having trouble gaining weight.

“I do need someone to push me,” he said.

Oakland had signed Marquis for the last half of the 2008 season and for 2009. Twice in eight games in 2008, he had been awarded the game ball for his play on special teams. He was smooth, elegant, a little quiet at first until he opened up. Working with him was a way for me to get into better shape as he became more fit. And to be honest, it was a way to show off, to show him what I could do.

That first week, we worked so hard lifting that he got sick almost every day. Threw up. He was drinking some kind of weight-gain shake, and it was tearing him up. We were lifting heavy weights continuously, working out ninety minutes or two hours, the longest break a minute, just boom, boom, boom. Soon he got into ridiculous shape. He would squat 405 pounds in sets of eight, and bench 315 pounds in sets of eight. He was the only person who could beat me at this one drill I devised—three push-ups and one pull-up, ten repetitions as fast as you could. He could do it in fifty-one seconds. My best was fifty-seven seconds. He was fast, very quick. He could dunk a basketball like it was nothing. He always found a way to win when we played H-O-R-S-E. He had an ugly stroke, but the ball went in.

If there was any sport he loved as much as football, it was fishing. He grew up in the desert, in Phoenix, but he was drawn to the water around the University of Washington campus in Seattle. In college, he kept pets—Hoss, a pit bull; Red, a red-tailed boa constrictor; and Vic Damone Jr., a python named after the alias Chris Tucker’s character used in the movie

Money Talks.

He still kept dogs, Boston terriers named Hercules, Dori, and Winston. He also had a fish pond that seemed to be ten feet deep in his backyard, filled with fish, some of which he had caught himself.

Fishing and football and his family meant everything to Marquis. After football, Marquis planned to make fishing his second career. He would become a captain and run his own charter busi

ness. He said he felt calm and peaceful on his boat. And he was terrific at fishing. He thought that being a charter captain would be fun, like football. It wouldn’t feel like work or be as stressful as an ordinary job. He once told the

San Francisco Chronicle,

“I used to go freshwater, but now I’m salt and that’s it. Don’t show me no lake, river, or nothing. It’s a drug. You get hooked. You need it, like you want a new pole or you want new reels. I just go out there and get it done.”

I

had also met Corey at the gym a couple months earlier. He was 6 feet 3 inches, 265 pounds, 12 percent body fat. You can look at people and tell they’re unique. I knew he was some kind of athlete when I noticed his pants or his gloves or something bore the logo of the NFL. Like Marquis, Corey was undersized. As a defensive end, he sometimes played against tackles who outweighed him by sixty or seventy pounds. He had gone undrafted out of North Carolina State in 2002, but caught on with Tampa Bay as a free agent. He played in six of the first nine games in 2002, then finished the season on injured reserve, unable to play in the Super Bowl as the Buccaneers defeated the Raiders. I’m not sure if Corey got a Super Bowl ring; if he did, he was modest about his accomplishments—I didn’t see him wear it. Still, against long odds, he had built a nice career for himself. Briefly, he and Marquis played together with the Buccaneers in 2004, but I don’t think they had known each other well.

Corey’s career had been one of extremes. He played on a Super Bowl team as a rookie, and in 2008 he played on a Detroit Lions team that lost all sixteen of its games. But he was known as a dura

ble, reliable backup. In high school in Richmond, Virginia, Corey was so relentless on the field that his nickname was the Tasmanian Devil. He played the same way in the pros. The Lions loved to talk about a play from the 2007 season. Corey had a strained hamstring muscle, and the Detroit coaches tried to replace him on the kickoff return team in a game against Chicago.

“Coach, I can give you one more play,” Corey told Stan Kwan, the Lions’ special teams coach. “I might not be able to walk after that, but I can give you one more play.”

So they left him in the game. The Bears tried an onside kick, but the Lions recovered. Corey made two blocks on the return, sprung his teammate for a touchdown, and the Lions won. While everyone else celebrated the touchdown, Corey limped to the sideline. He was finished for the day, but he had done his job. The next day, Rod Marinelli, Detroit’s head coach at the time, showed a replay of Corey’s blocks to the team as a sign of determination and toughness.

“Rod just showed the play over and over,” Kwan told the

Detroit News

. “Right then and there, his teammates knew he was a team guy first. He’s not the fastest guy. He wasn’t the tallest or biggest guy for a defensive end, but his heart was bigger than everybody else’s.”

Corey became a free agent after the 2008 season, but he seemed confident that he would catch on with a team by training camp, maybe even in the next month.

“Are you worried?” I asked him.

“I’ll be fine,” he said.

He could be quiet and serious, until he opened up. He was curious. He wanted to hear stories from you more than the other way around. But he had a great, loud laugh. And if you said something he didn’t quite believe, he would give you a grinning, sarcastic, “Whaaaat?”

Corey had a sweet tooth for brownies and ice cream, had tried yoga, knew how to juggle, tinkered with computers, and, unlike many superstitious athletes, deliberately avoided pregame routines. He once told the

Grand Rapids Press

, “I have an antiroutine. I try to do something different before every game.”

I was training Marquis, and I told Corey, “You need to come work out with us.” The three of us were pretty much together four days a week, if not five. We would probably put in twenty-plus hours together, working out, having lunch. They were great guys to hang out with. And it got me in great shape, too.

I asked them about their workouts in the NFL, and they said it was just basic lifting, all power lifts designed for pure strength. We did a lot combination exercises besides the regular bench, squat, and leg press. We did auxiliary lifts, side raises, curls, shrugs, and lunges, trying to build stamina, endurance, conditioning. I was trying to drop their body fat and put muscle on them at the same time. They both got a whole lot of gains. Corey’s bench press went up 25 pounds in three months: He was benching eight reps of 335 pounds. Corey didn’t drink alcohol. Not an ounce. He and Marquis always talked about other players, coaches, people they had in common. After the NFL, I think Corey wanted to get into coaching. I never heard him say a bad word about anyone.

They would laugh at some of my routines. I’d put four plates on the bar and do a set of ten Romanian dead lifts—bending at the waist, legs slightly bent but locked, back flat, butt out—and lift 405 pounds to my waist. That hurts. It’s a lot of weight, particularly on your spine. They looked at me like why would anybody want to put that much stress on their body? We got into a groove and worked hard, and they made a lot of gains. Then it was almost time for Marquis to head out West. Before he left, he wanted to take us fishing.

A week earlier, Corey and I had gone along on Marquis’s boat, to the same place we were headed today. I didn’t know much about

deep-sea fishing. Nothing, in fact. I had grown up in Chardon, Ohio, outside of Cleveland. When I was young, my mother would take me to a park, and I’d walk to the end of the dock and drop a line. You could see the bluegills and sunfish. You would literally drop the worm and put it to their face. So this deep-sea business was basically new to me. I had gone out only once, off Virginia Beach, when I was seven years old. I don’t even think I cast my line once. I just threw up all day. With Marquis and Corey, I was just along for the ride.

Marquis kept saying, “I’ll take you out fishing. You need to come. Your whole body will be sore after a day of fishing. It’s a good feeling, a different kind of sore from working out.”

And fishing meant going out to the Gulf of Mexico—more than fourteen thousand feet at its deepest point. The Gulf produces a quarter of the United States’ natural gas and an eighth of its oil. It also provides some of the world’s most abundant fisheries. By the beginning of the decade, about 20 percent of the nation’s commercial fish and shellfish were harvested from the Gulf, along with 40 percent of the country’s recreational finfish. The world’s largest fish—whale sharks, which grow to fifty feet—were also being spotted in the Gulf in record numbers. They were apparently attracted by plankton blooms fed by fertilizer and other nutrients flowing from the Mississippi River. Fish, shrimp, and squid were also drawn to the cooler, plankton-rich waters that upwelled along the continental shelf off of Florida.

Corey and I could not figure out why Marquis loved fishing. It was so much work. The weekend before, we got to Marquis’s house at four thirty in the morning and were on the water by six fifteen. We went more than seventy miles out. He would catch a fish every five minutes: red snapper, grouper, lemon sharks, amberjacks. Corey and I didn’t know what to do with the poles or how to get the fish off the hook or put the bait on. Marquis would laugh at us.

“Y’all are worthless!” he said.

Then he would say, “Hold on,” and stop what he was doing and get us set up. Then he would start fishing again—and every time he cast his line, he seemed to pull up a fish.

He would try to tell us how to tie certain knots, and we were like, “Yeah, whatever, dude. Can you help us get this fish off our hook?”

I caught my first fish and I was like, oh my God, forget this. I was so confused. Why would anybody like this? It took me almost fifteen minutes to get the damn fish up. A big amberjack. As soon as I made a little leeway, it yanked out everything I had reeled in. It fought like a shark. My back and shoulders were burning. I kind of wedged the pole between my legs and told Marquis, “I’m taking a little break.” I couldn’t imagine anyone pulling up a giant marlin or something.

“Pull, pull!” Marquis kept yelling at me and laughing. By then, he had probably already caught five fish.

It was choppy on the ride back that first time, and we were going thirty-five miles an hour. Corey and I kept saying, “How much longer, how much longer?” We were ready for it to be over. When we finally got back to the dock, Corey and I got in Marquis’s truck while he and a friend iced the fish and cleaned the boat. I was so tired and hungry and cold. We were wet. We smelled.

“No way in hell we’re doing this again,” Corey and I said to each other.

We didn’t get home until ten. Two nights later, we got together and grilled and fried some of the snapper, the shark, the amberjack, and the grouper. I don’t like fish. I don’t like the smell or the texture or the taste. They kept giving me a hard time.

“You gotta try it,” Marquis would say, laughing. “You’re such a bitch. Don’t be a bitch. It’s so much better fresh. Trust me.”

Finally, I tried it. It wasn’t bad. I was surprised. Not that I was going to go out to a seafood restaurant any time soon.

Marquis was so happy that night. We played Rock Band, the video game, and he kept telling his young daughter, Delaney, “Inside voice, inside voice,” until she put on this one song and began screaming into the mike and we all started laughing. All of a sudden, he was telling her, “Louder, louder!” It was the cutest thing.

Before he left for Oakland, Marquis wanted to go out fishing one more time.

“I don’t know,” I tried to tell him, but he kept saying, “Come on, I may not get a chance to go out again until this time next year.”

Corey and I debated it.

“All right, we’ll do it,” we said. “Why not?”

Any time I got to spend with those guys was fun.