"Non-Germans" Under the Third Reich (74 page)

Read "Non-Germans" Under the Third Reich Online

Authors: Diemut Majer

Tags: #History, #Europe, #Eastern, #Germany

Jews, of course, were subject to additional special laws. They had been completely excluded from telegraph services since August 1940,

6

as well as from telephone communications and the possession of telephones. In December 1941 the post no longer accepted packets, parcels, or insured parcels from Jews “

to avoid the risk of epidemics.

”

7

News media privately owned by “non-Germans” were also subject to farreaching restrictions. Numerous prohibitions were issued early on, restricting radio reception; these were of dubious effect, however, as stated in the aforementioned Security Service Reports on Domestic Issues. During the military administration, foreign radio sets held by poles who were “suspected of listening to Allied broadcasts” were confiscated, as were those owned by persons who were “notorious Polish chauvinists.”

8

The civil administration rapidly followed suit and—backed up by corresponding proclamations in the

kreise

9

—decreed in December 1939 that all radios held by Poles and Jews be confiscated, to be collected by January 25, 1940, and that all “superfluous aerials” be removed;

10

the responsible administrative authority (

Kreishauptmann or stadthauptmann

) could issue exemptions from the duty of surrender in individual instances to members of the Ukrainian and Góral population in a phased “racial” approach (i.e., for political “good conduct”); Reich and ethnic Germans could keep their radios but were required to register all sets.

11

As was to be expected, the duty of surrender was not obeyed in all cases; according to a report by SS-

Sturmbahnführer

Joseph Meisinger on the security situation in the Warsaw District at a meeting of the Reich Defense Committee on March 2, 1940, only 87,000 out of a total of around 140,000 radio sets in Warsaw had been surrendered; many radios had been destroyed in the fighting, but many others were being hidden.

12

In view of the low number of available police officers, the situation is likely to have been similar in the other districts.

For other luxury goods, such as binoculars, cameras, and so on, there were no central confiscation regulations and surrender obligations as were common, for instance in the

Reichsgau

Wartheland; all that can be proved is the registration and confiscation of film equipment, skis, and ski boots for the use of the Wehrmacht.

13

No doubt more extensive individual regulations were issued by the district and

Kreis

administrations on the basis of the Confiscation Decree of January 26,1940, or by single acts of the police for “the public benefit” in line with the principle that, whenever the German civil authorities had a requirement, they could seize the private property of the “non-Germans” without objection.

A concluding survey of the discriminatory measures in these areas high-lights two specific features: compared with the radical practices common in parts of the Annexed Eastern Territories and in the parts of eastern Poland occupied by the Soviet Union, relatively tolerable living conditions reigned in the General Government.

14

However, this applied only to the Polish population; the legal and administrative extinction of the Jews, based on the model of the Reich, was tackled with single-minded determination. Whereas in the Warthegau, for instance, a radical isolation of the Polish population from the outside world (travel bans) and from key information media, cultural goods, and commodities was implemented down to humiliating, petty harassment, there still existed in the General Government—despite the restrictions in force—an opportunity for personal freedom of movement, freedom of communication and information, and protection of private property, either because the regulations in force were not so far-reaching or because there were simply no facilities for supervising their observance. Nevertheless, the practice of special law, especially in the professional and labor law sectors, led to predatory policies running counter to all principles of economic reason. As could be expected, these policies therefore implemented their own objectives (the General Government as an inexhaustible supplier of willing labor, industrial goods, and foodstuffs) ad absurdum. As a report of the Military District Command of the General Government of January 7, 1943, soberly ascertained, the consequences of the isolation and expulsion measures, of the “psychologically mistaken treatment,” of the “erroneous harshness” and the “complete disregard [for the Poles] in conjunction with poor social welfare,” were the ruin of trade and industry, poor labor productivity, falling production figures, failure to meet the quotas imposed by the Reich, and at an early date (since around 1941 and to a larger extent since 1942) an increasingly anti-German mood in all areas,

15

which was only reinforced by the professional and moral failure, the corruption, and the “master-race attitude” of the leadership and numerous departments.

16

The most paralyzing and destructive factors, however, were the largely contrary policies of the administration and the police, the jurisdictional chaos and legal uncertainty in this strained relationship, and the lack of any solid line by the administrative leadership against the claims to power of the police or in the question of the treatment of the “non-Germans.”

These conflicts did not affect the relationship between the administration and the police in all areas. In particular, the fact should not be ignored that they collaborated closely in many areas of the treatment of “non-Germans.” The administrative leadership of the General Government, which had developed in an atmosphere of anti-Polish sentiment,

17

was also convinced in the beginning, as were the police, that it could establish a

permanent

colonial regime on the basis of pure repression. The numerous resettlement and evacuation measures, the indiscriminate taking of hostages and executions, and the ruthless collection of laborers right up to manhunts demonstrate that system of blind failure to appreciate facts that was so characteristic of the Nazi regime. As established by the aforementioned report of the Military District Command of the General Government, these actions created the best conditions for acts of desperation, criminal gangs, and so forth, leading to the Poles’ fear that “all rights to exist were to be taken from them and that they were to meet the same fate as the Jews.”

18

When the difficulties became insurmountable, there were calls by the police for increasingly drastic measures, as shown by the recruitment of labor, which in turn strengthened the Polish resistance. When it was too late, the need for a change of course was recognized, but it never passed the stage of promises and small changes to the “

Fremdvolk

policy,” and nothing at all was done to curb the omnipotence of the police.

For instance, the government of the General Government attempted to win back the powers of the police, which it had initially transferred so generously—in particular the infinite police administrative law in section 3 of the Decree on Security and Public Order in the General Government of October 26, 1939.

19

A draft unified police administrative law in the General Government submitted in 1941 eliminated the police administrative law of the SS and police; the ranks of the regular police performing specific duties (gendarmerie and uniformed police) were no longer to be subordinate to the head of the regular police, and above him the HSSPF, but to the

Kreis

authorities and

Stadthauptleute.

20

However, as with all other efforts to curb the growing powers of the police, it was too late. The HSSPF had no intention of giving up the powers transferred to him;

21

in addition, as regards its application to “non-Germans,” substantive police law gradually lost its—in any case minor—importance.

The needs of the moment in the eyes of the police were more than ever the proven means of guidelines and specific directives, requiring no legal basis for authorization and for which neither the consent nor the notification of the administrative authorities was necessary. Furthermore, from 1943 on, the treatment of the “non-Germans” was increasingly enforced in the form of acts of terror. The governor general, who had been concerned about preserving his own powers since the replacement of HSSPF Friedrich Wilhelm Krüger by SS-

Obergruppenführer

Wilhelm Koppe in fall 1943, and with an eye to the security situation, which was “falling to pieces,” allied himself ever more closely with the police and indeed supported their approval for the hardest possible line against the Poles. For this reason the governor general had given the police unheard-of powers in 1943, far exceeding their already extensive jurisdiction (e.g., jurisdiction for courts-martial).

22

These included the Decree on the Combating of Attacks on the German (

Aufbauwerk

) of October 2, 1943,

23

through which it was hoped to gain the upper hand over the Polish resistance movement.

24

This decree entailed the complete annulment of all concepts of police law by instituting the death penalty without any court proceedings for any violation of any directive by German agencies, treating any prejudicial conduct as an “attack on the German (

Aufbauwerk

).”

25

With this decree, the police obtained what they regarded as the

ideal police law,

with one single offense and infinite omnibus provisions, as well as a single penalty, the death sentence, which could be used as the basis for all forms of police action, particularly for raids, including the execution of hostages, resistance fighters, and so on. As usual, the governor general considered curbing these powers again when it was discovered that the situation was not markedly improved by the rigorous approach adopted by the police.

26

And as usual, it was too late to recall the furies that had been let loose.

The predatory practice of the administration had thus not only successfully prevented the realization of its own goals within the shortest possible period, but it had incurred the enmity of all sections of the population and reduced the country to a “total starvation level” (according to Frank), both culturally and economically. Its transfer of extensive powers to the police had also robbed it of any opportunity to influence the treatment of the “non-Germans,” had crucially strengthened the Polish will to resist,

27

had assisted the revolutionary violence of the police in all key aspects, and had thus cooperated in the elimination of all conventional concepts and forms of administrative acts in favor of a regime of pure brutality, which left behind it nothing but destruction and ruins.

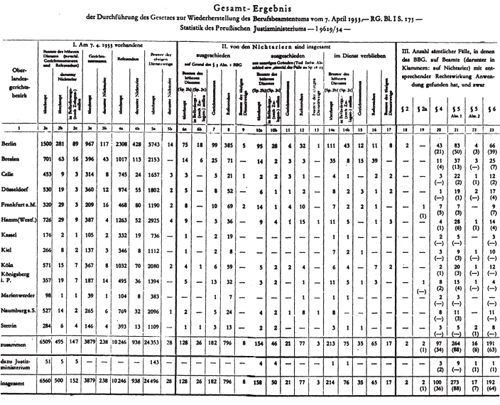

FIG. 1 Statistical survey of the Prussian Ministry of Justice, 1934. Reproduced in H. Schorn,

Der Richter im Dritten Reich

(Frankfurt/Main, 1959), 730 f., from original in Geheimen Staatsarchiv Preussischer Kulturbesitz, Rep. 84a.

FIG. 2 Celebration of the presentation of the national emblem swastika pin to be worn on the justices’ robes in the Criminal Court Berlin-Moabit, October 1, 1936. Ullstein Bilderdienst.