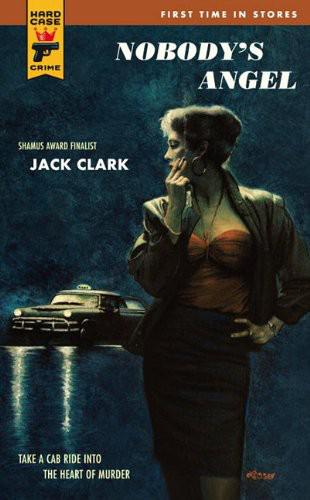

Nobody's Angel

Authors: Jack Clark

NOBODY'S ANGEL

By Jack Clark

Copyright 1996, 2010 Jack Clark

SKY BLUE TAXI

INITIAL CHARGE $1.20

FIRST 1/5th MILE .20

EACH ADDITIONAL 1/6th MILE .20

WAITING TIME (EACH MINUTE) .20

ADDITIONAL PASSENGERS (EACH) .50

TRUNKS .50

HAND BAGGAGE CARRIED FREE

(RATES IN EFFECT FROM MARCH 1990 TO JANUARY 1993)

CITY OF CHICAGO

INCORPORATED 4th MARCH 1837

PUBLIC PASSENGER CHAUFFEUR'S

LICENSE

21609 EDWIN W

MILES

Department of Consumer Services

It was a beautiful winter night but everybody was home hiding from a snowstorm that would never arrive. Everybody but the cabdrivers. We were sitting around the Lincoln Avenue roundtable--a group of rectangular tables and the surrounding booths in the back of the Golden Batter Pancake House--everybody bitching and moaning, which is the routine even on good nights.

Escrow Jake was into a familiar rant about TV weathermen. "When they say, 'Whatever you do, don't go outside,' what they really mean is: 'Stay home, watch TV and see how fast my ratings and my paycheck go up.'"

Jake had been a lawyer until he got disbarred for squandering escrow accounts at various racetracks. He was still a degenerate gambler but now he drove a cab to feed his habit. Only his very best friends called him Escrow to his face.

In the booth behind Jake, Tony Golden and Roy Davidson were schooling a rookie in the art of survival. Golden had grown up on the black South Side. Davidson was white, from the hills of Kentucky. But they were the best of friends. And they both loved the rookie. Everybody did.

There weren't many Americans entering the trade, and the kid was white to boot, which made him about as rare as a twenty dollar tip.

"Don't go south," Davidson warned him.

"Keep your doors locked," Golden advised. "Especially that left rear one. They love to slip in that left rear door."

"Don't go west," Davidson added.

"Then they can sit right behind you and when the time comes, bam, they're over the seat."

"Don't go into the projects."

"I don't even know where all the projects are." The rookie sounded shaky.

"You know what Cabrini looks like?" Davidson asked.

The rookie said he did. Everybody knew what the Cabrini-Green housing project looked like.

"That's all you got to know. Don't go south. Don't go west. Don't go anywhere looks like Cabrini."

"But I won't know till I get there," the rookie said.

Good point, kid, I thought. Good point. And I remembered my own days as a rookie and my first trip to the pancake house.

I'd cut off another taxi. The cab came around me at the next red light, pulled into the intersection, then backed right to my bumper.

The guy who'd gotten out wasn't that big, but he walked back slowly, with plenty of confidence, ignoring the horns that started to blare as the light turned green.

"Jesus, you're white," Polack Lenny said as cars squealed around us. "Why you driving like a fucking dot-head?" I was to discover that this was Lenny's harshest insult.

"Sorry. I didn't see you," I lied. "Just trying to get back to O'Hare."

"Oh, boy. How long you been driving?"

"Couple months," I admitted.

"Never go back," he said. "Haven't you learned that yet? You never go back."

"It's really moving out there," I said.

He shook his head sadly. "Stop by the Golden Batter on Lincoln some night. You can buy me a cup of coffee."

He jogged back to his cab, jumped in, and made the light as it was changing. I waited for the next one, then wasted twenty minutes speeding to O'Hare to find the staging area full of empty cabs.

Later that night I bought Lenny a cup of coffee. It was the first of a few thousand conversations we would have at the roundtable. It was easy to learn when Lenny was talking. "People don't want to hear how bad business is," he told me that first night. "They got problems of their own. So if they ask, just lie and say you're having a great time. You might even start to believe it."

Tonight, drivers were remembering and concocting long trips. St. Louis, Louisville, Miami, Los Angeles, Anchorage. Lenny, sitting at the head of table number one, cut everybody off. "You want to talk about long trips, I'll tell you about a long trip."

Ace, sitting across from me, winked.

"Here we go," I whispered.

But the whole place shut up. There must have been thirty drivers, and many had already heard Lenny's

favorite story. I'd heard it several times myself. But this is the night I always remember.

"This is years ago," Lenny said. "I'm on LaSalle Street in the Loop when this guy in a bowler hat flags me with his cane. 'Buckingham Palace, please.' Like it's right 'round the corner. 'Listen, pal,' I tell him. 'I can get you to the fountain for a couple of bucks but the palace is about four thousand miles.' 'The palace, please.' Well, I'm getting a little annoyed. 'You think I got wings?' "

Lenny does the English guy with puckered lips: " 'I believe there's a ship leaving the Port of New York in seventeen hours, twelve minutes.' So, what the hell, I get on the horn and dispatch comes back with an even twelve grand. 'Get the money up front and save the receipts.' "

"Twelve thousand dollars?" the rookie whispered as Lenny began to reel in the line.

"The English guy opens his briefcase and counts out twelve thousand in hundred dollar bills. Then he says, 'Drive on, Leonard.' "

Leonard. Half the room died. It was a brand new touch.

"Six days later we pull up in front of Buckingham Palace and he says, 'Ta-ta, Leonard. Thank you very much.' And he hands me a ten pound tip."

"Lenny, you are so full of shit," someone said, and someone else said, "You're just figuring that out?"

Didn't faze Lenny. "Hear me out. You ain't heard the kicker. So I start back for the docks. Haven't gone two blocks when all a sudden I hear, 'Sky Blue! Sky Blue!' I stop and here's this guy lugging a couple of guitars and a suitcase. 'You're a Sky Blue Cab from Chicago, right?' 'What's it look like, pal?' 'Can you take me back there? I was just on the way to the airport but I hate to fly.' 'Well, sure. But, look, it's twelve grand and I gotta have it up front. Cash.' 'That's no problem,' he says. 'Can you get me there by Saturday night? I got to be at 43rd and King Drive by six o'clock.' "

Lenny held up his hand like a cop stopping traffic. " 'Whoa. Look. Sorry, pal, nothing personal but ' " He gave it a long beat. " 'I don't go south.' "

The place exploded in laughter. Even guys who'd heard it before were howling. I looked over and the rookie was laughing along with the crowd but you could tell he didn't really get it. He was probably thinking about driving a truck for a living or something sensible like that.

Clair, my favorite waitress, came by with a coffee pot and a rag to clean up the spills. She caught my eye and flashed a smile.

Ace winked. "She likes you, Eddie."

"She's married."

"And?"

"And she's not that kind of girl," I said. But in my dreams she was.

"The things you don't know about women," Ace said.

All taxicabs shall have affixed to the exterior of the cowl or hood of the taxicab the metal plate issued by the Department of Consumer Services. No chauffeur shall operate any Public Passenger Vehicle without a medallion properly affixed.

City of Chicago, Department of Consumer Services, Public Vehicle Operations Division

It was another quiet night--the tail end of that same winter--the last time I saw Lenny.

I was northbound on Lake Shore Drive, fifteen over the special winter speed limit, which was supposed to keep the road salt spray from killing the saplings shivering in the median.

The lake was a vast darkness on the right. To the left lay the park and beyond that a string of high-rent highrises climbed straight into the clouds.

A shiny Mercedes shot past in the left lane. A rusty Buick followed along. I flipped the wipers on to clear the mist that had risen off the road.

A horn sounded. I looked over as a brand new cab slipped up the Belmont Avenue ramp. I slowed down a bit and the cab pulled alongside. The inside light went on and Polack Lenny pointed a long finger at his own forehead. I couldn't read his lips but I knew that he was once again calling me a dot-head. "Hey, Lenny." I turned my own light on and gave him the finger in return.

For most of the years I'd known him, we'd both driven company cabs. I hadn't known his real name until he'd won a taxi medallion in a lottery and put his own cab on the street. I'd been one of the losers in that same lottery, and I was still driving for Sky Blue Cab.

LEONARD SMIGELKOWSKI TAXI, Lenny's rear door proudly proclaimed. His last name took up the entire width of the door, which had some obvious advantages. He might never get another complaint. Everybody'd get too bogged down with the spelling.