Newfoundland Stories

Read Newfoundland Stories Online

Authors: Eldon Drodge

Tags: #Newfoundland and Labrador, #HIS006000, #Fiction, #FIC010000, #General, #FIC029000

Newfoundland

Stories

Newfoundland

Stories

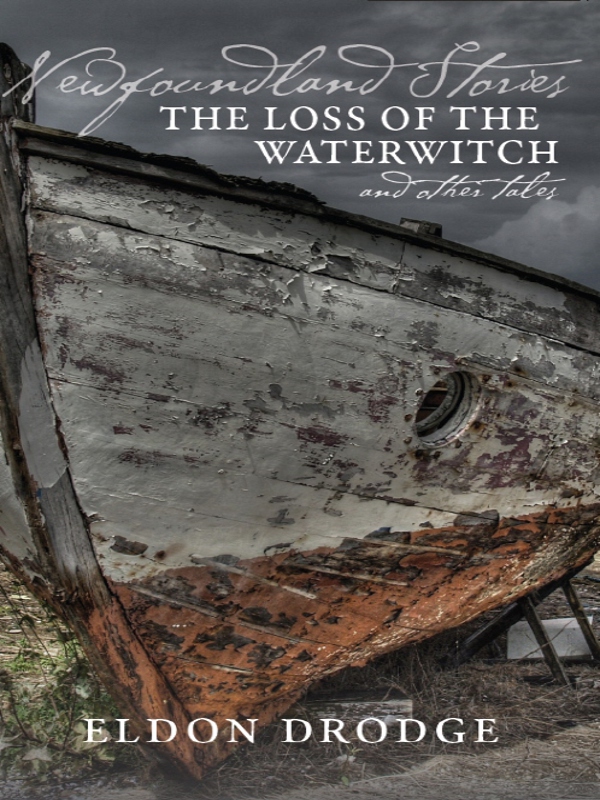

THE LOSS OF THE WATERWITCH

and other tales

ELDON DRODGE

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Drodge, Eldon, 1942-

Newfoundland stories : the loss of the waterwitch and other tales / Eldon Drodge.

ISBN

978-1-55081-331-9

I. Title

PS8557.R62N48 2010 Â Â Â C818'.6 Â Â C2010-905852-6

© 2010 Eldon Drodge

Cover Design: Alison Carr

Cover Photograph: John Nyberg

Layout: Rhonda Molloy

Â Â Â BREAKWATER BOOKS

BREAKWATER BOOKS

Â

WWW

.BREAKWATERBOOKS.

COM

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior written consent of the publisher or a licence from The Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright). For an Access Copyright licence, visit

www.accesscopyright.ca

or call toll free to 1-800-893-5777.

We acknowledge the support of the Canada Council for the Arts which last year invested $1.3 million in the arts in Newfoundland. We acknowledge the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund and the Government of Newfoundland and Labrador through the Department of Tourism, Culture and Recreation for our publishing activities.

PRINTED IN CANADA.

dedicated

to my four grandsons,

Daniel

Zachary

Benjamin

Jack

contents

What Happened at Devil's Cove?

Some of these stories are based on actual events and real characters.

The others are purely from the imagination.

All embody the essence of Newfoundland, past and present.

S

amuel Spracklin, captain and owner of the

Waterwitch

, was worried. Having departed from St. John's in the early evening, his schooner, with twenty-five passengers and crew on board, was beating into the teeth of a northwesterly gale in late November 1875, en route to her home port of Cupids in Conception Bay. After more than three hours of hard sailing under full canvas, the vessel was still only abreast of Flatrock, a mere fifteen miles out of St. John's with another thirty-five miles to go, and the storm was intensifying. The other twenty-four people she was carrying, including Spracklin's son, Samuel, Jr., were equally apprehensive. Darkness and driving snow had diminished visibility to almost zero and the

Waterwitch

was taking on water each time her gunnels were raked and pulled under by the oncoming waves.

The weather had been a bit on the rough side when they left, but Spracklin had been undeterred and had sailed without a moment's hesitation. He had often taken his sturdy vessel out in weather as bad or worse without any problems. His ship's load included the winter provisions â food, clothing, and other necessities they would need to sustain them through the coming winter months â and he was anxious to get home to Cupids with his cargo. This would be his last voyage for the year. Within the next couple of weeks the

Waterwitch

would be berthed in Cupids for the winter and would remain tied up there until the following spring.

He had reckoned on making Cape St. Francis inside of three or four hours, and would then be able to take his vessel home comfortably in the lee shore of Conception Bay. At the time of his departure, he could not have anticipated the serious deterioration in the weather or the sudden shifting of the wind from the northeast to northwesterly. He briefly considered turning around and heading back to St. John's with the wind on their stern, but it was only a few more miles to the Cape, after which they should be okay, so he opted to continue on. With darkness and swirling snow limiting his vision and with no way of taking a reading to confirm his exact location, he was relying totally on his compass, his knowledge of winds and tides, and his long years of experience on the sea. Above all else, he knew that he dare not venture too close to the treacherous coastline in this area or he would run the risk of his schooner being dashed to pieces on the rocks.

Another hour of torturous progress saw them just off Pouch Cove, the last settlement before Cape St. Francis. The

Waterwitch

was by then being battered mercilessly, and the crew worked feverishly to keep her bow to the wind and to pump out the water that rushed in every time the schooner plummeted into the cavernous troughs that separated the towering waves. Most of the crew members were seasoned seamen, but few of them had ever experienced sea conditions as bad as this before. For despite Spracklin's calculations, the wind and the tides had carried the vessel much closer to the rocky shore than anyone on board realized, and when this fatal mistake was discovered it was too late to do anything about it. The

Waterwitch

was minutes away from crashing onto the rocks, and Spracklin and his crew, knowing their vessel was doomed, frantically tried to lower canvas as they braced themselves for the impact.

The crash, when it came, was horrendous. Some on board, including the four women, were either thrown from the vessel and dashed against the rocks or cast into the churning water. Some were killed outright in the crash. Of the twenty-five who had started the voyage, only thirteen, including Spracklin and his son, were left alive, and barring divine intervention, they too would soon follow their unfortunate shipmates.

The

Waterwitch

was wedged between two large rocks at the base of a towering cliff and, with any luck, might conceivably remain intact there for a while. Spracklin knew, however, the ship would eventually be battered to pieces by the pounding sea. He concluded that their only chance for survival rested on one of them scaling the cliff, finding help, and getting back before the vessel was destroyed.

He decided that he would be the one to try to climb the cliff. He selected one other seaman from his remaining crew to accompany him, Richard Ford,

1

a man whom he knew from personal experience to be strong and daring, and one with whom he could place his complete trust. Their first major hurdle was to make it from the vessel onto the rocks and then to the cliff. The courageous manoeuvre required agility and precise timing, and both men, after a number of false starts, soon found themselves standing on a narrow ledge at the base of the cliff. Their ascent could not be delayed, for with every passing second they were exposed to the risk of being sucked into the sea by the pounding surf that drove at them and saturated their clothes.

The ledge on which they stood zigzagged steeply upward for about a hundred feet before terminating into the face of the cliff, and the two men were able to cover that valuable ground in short order. Then their real difficulties began. From there to the top there was nothing but slippery, precipitous granite. Searching for finger and foot holds, Spracklin and Ford began a journey more dangerous that any other they would ever undertake in their lifetimes: the remaining four hundred feet to the top. By virtue of great physical strength and enormous willpower, they inched their way upward. Twenty minutes later, they could no longer hear the shouts of the stranded men over the blasting of the wind.