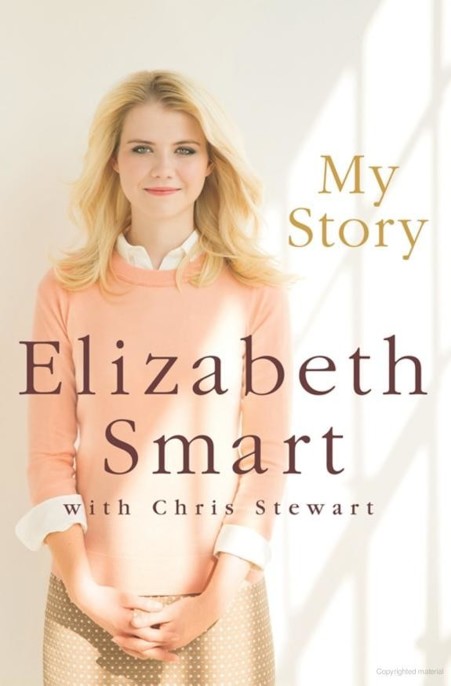

My Story

Authors: Elizabeth Smart,Chris Stewart

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Memoirs, #True Crime, #General

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way.

Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at:

us.macmillanusa.com/piracy

.

This book is dedicated to the safe return of missing children everywhere.

Acknowledgments

My parents, Ed and Lois Smart.

My immediate and extended family.

People who searched and prayed for me everywhere.

Chris Stewart.

And my wonderful husband, Matthew Gilmour.

Contents

The power of choosing good and evil

is within the reach of all.

—Origen Adamantius

For we are troubled on every side, yet not distressed; we are perplexed, but not in despair; persecuted, but not forsaken; cast down, but not destroyed.

Prologue—2 Corinthians 4:8–9

November 2001

We had just walked out of the ZCMI store in downtown Salt Lake City. The heavily tinted windows, with their grated iron accents, were at our backs as we waited to cross the street. Traffic was light. I remember it was cold. The Mormon temple and visitor center was just a block away and high-rise buildings rose on every side. Salt Lake City was getting ready for the Winter Olympics and there was construction all around. The sky was gray and clear, and the sun was moving quickly toward the western horizon. There weren’t a lot of pedestrians—winter was coming on—so the beggar was hard to ignore, standing among the well-dressed crowd.

He didn’t seem to notice as we walked by. I was on my mother’s right, my little sister on her left, holding my mother’s hand. We had been shopping, and I carried a couple of little bags. I was a teenager, but just barely, with blond hair and blue eyes. As we walked, I remember glancing at my mother. She was very pretty. I liked being with her. She was one of my best friends.

Salt Lake City was not a dangerous place, and I had the luxury of growing up with a mother who was open and unassuming. Her demeanor was friendly yet careful.

Standing by the beggar, waiting to cross the street, I looked and made eye contact with him; my brothers had already seen him and had come back to ask my mom if we had any work for him.

Mom glanced at him warily, not wanting to stare. I don’t remember a lot about him, but I do recall that he was clean-cut and well groomed. No beard. No robes. No singing or talking about prophets or visions or being the Chosen One. All of that would come later. For now, he appeared to be nothing more than a normal guy who had hit a rough patch in his life. He certainly didn’t seem to be dangerous or threatening.

“I thought he was a man down on his luck,” my mom would later testify. “He just lost his job, looked young enough that maybe he had a family, people he was responsible for.”

So she walked toward him, five dollars in her hand.

I held back, my hair blowing in the autumn wind.

He glanced in my direction, seeming to take me in from the corner of his eye. I gave him a quick smile. I felt sorry for him and was happy when my mother handed him the money.

What I didn’t know—but would later learn—was that he had been watching me very carefully as we walked toward him. He had taken the opportunity to study me further as my mother searched through her purse. He remembered everything about me: the clothes that I was wearing, my blond hair, the way I looked up at my mother, the color of my eyes.

And though he was very careful not to show it, he decided at that moment that I was the one.

Elizabeth

It’s funny, some of the things that I remember, many of the details forever burned in my mind.

It’s as if I can still smell the air, hear the mountain leaves rustle above me, feel the fabric of the veil that Brian David Mitchell stretched across my face. I can picture every detail of my surroundings: the tent, the washbasin, the oppressive dugout full of spiders and mice. I can feel the cut of the steel cable wrapped so tightly around my ankle, the scorch of the summer heat lifting off the side of the hill, the swaying of the Greyhound bus as we fled to California. I can still see the people who were around me, their blank expressions, their fear of how we were dressed, my veil and the dirty robes, the looks of confusion in their eyes.

I remember so many overwhelming feelings and emotions. Terror that is utterly indescribable, even to this day. Embarrassment and shame so deep, I felt as if my very

worth

had been tossed upon the ground. Despair. Starving hunger. Fatigue and thirst and a nakedness that bares one to the bones. Intruding hands. Pain and burning. The leering of his dark eyes. A deep longing for my family. A heartbreaking yearning to go home.

All of these memories are a part of me now, the DNA inside me. Indeed, these are the things that have moved and shaped me, sometimes twisting, sometimes wrenching me into the person I am today.

Sometime long before I was taken, I had been told that when someone dies, the first thing you forget is the sound of their voice. This thought terrified me.

What if I could no longer remember my mother’s voice, a sound I had heard every day of my life!

I started to think of her, and other members of my family and their voices. I started to think of all the things my mom used to tell me every day:

Have a good day at school. I love you. Have a good night

. I would have given anything to hear her at that moment.

Every morning she used to sing at the top of her lungs,

“Oh what a beautiful morning…”

I used to hate it.

What would I have given to hear her voice again!

Over the first few weeks of captivity, I forced myself to think of things like that. I remember sitting in the heat of the summer, the sun baking on my back, forcing myself to think of my mom’s voice, her laugh. How beautiful she looked in her black skirt and gold top. The shape and the color of her eyes.

But there were other feelings too. And though it might be hard to understand, a few of them were good, for they show the things you cling to when everything is gone.

I remember the pure rush of gratitude for any time that I could sleep. The realization that I would live another day! Relief when the sun went down and the heat gave way to the cool of the night. Gratefulness for food or water. A few minutes when I might be left alone. The ability to slip into a state of pure survival, a state of blankness, a quiet and painless place where I could shut the world down.

Looking back, I realized that at one point, early on the morning of the first day, something had changed inside me. After I had been raped and brutalized, there was something new inside my soul. There was a burning now inside me, a fierce determination that no matter what I had to do,

I was going to live!

This determination was the only thing that gave me any hope—the realization that as long as I could survive one more day or one more hour, I might find a way to get back home.

I also discovered something that is harder to imagine, and much more difficult to explain.

Sometime during the first couple of days, I realized that I wasn’t alone. There were others there beside me, unseen but not unfelt. Sometimes I could picture them beside me, reaching for my hand.

And that is one of the reasons I am still alive.

*

When I think back on those dark days of my capture, I realize my story didn’t start on the night that David Brian Mitchell slipped into my bedroom and held a knife at my throat. In an odd way, my story began a few days before. Sunday afternoon. In my home. Just a few days before my world was torn apart.

Over time, I have gained an enormous appreciation for what I experienced on that Sunday. It has helped me to keep perspective. It helped to give me hope. And it helped me understand a little better why things might have happened the way they did.

Sunday School

Two days before I was taken, I was sitting in my Sunday school class, surrounded by a group of other fourteen-and fifteen-year-olds. There were maybe seven or eight of us, a mix of boys and girls. Some of the kids were listening, but not everyone, for we were teenagers, you know. Looking around me, I was comfortable, for these kids were my friends. I had grown up with them, gone to school with them, eaten snacks at their houses, giggled with them on the playground. We knew one another well.

Though there was some horseplay among the class, for the most part I was quiet. I don’t know if I was shy, but I guess I was. I just didn’t feel a need to stand out. It surprises some people when I tell them that. Most of them picture me as an outgoing teenager. A cheerleader type, I think. But I wasn’t. I was kind of quiet. A very obedient child. A 4.0 student. I played the harp, for heaven’s sake! How un-cheerleader is that!

Some people say I’m pretty. Blond hair. Blue eyes. But I promise, I’ve never thought of myself that way. As a fourteen-year-old girl sitting in my Sunday school class, I certainly didn’t think of myself as beautiful. Honestly, I don’t think I ever thought about it at all. Some of the girls I knew were boy-crazy, but I never thought about those kinds of things. I didn’t wear makeup. I had never had a boyfriend. The thought had never even crossed my mind. My favorite things were talking to my mom and jumping on the trampoline with my best friend, Elizabeth Calder. We just liked to have fun together. But our idea of fun wasn’t chasing boys, or prank calling other kids in our class. In almost every way, I was still a little girl.

And one thing that I can say for certain is that I didn’t understand the world.

I remember pressing my white cotton dress—printed tulips with light-green edging—with my hands while listening to my teacher. To most of us kids, he seemed to be about a hundred years old, with his gray beard and white hair. But we liked him. I felt he cared about us, even if we didn’t listen to him all the time.

That morning, my teacher said something that hit me in a way that few things ever had before.

“If you will pray to do what God wants you to do, He will change your life,” he said.

I pressed my dress again, my head down. I was listening carefully to him now. I don’t know what it was, but there was something in the way he said it, the intensity of his voice, that made me realize that what he was saying was important.

“If you will lose your life in the service of God, He will direct you. He will help you. So I challenge you to do that. Commit to the Heavenly Father, and He will guide your way.”

But what can I do to serve God? I asked myself. I’m just a little girl. I don’t know anything. I can’t do anything. What path could He even guide me on?

I didn’t know the answers to these questions. But I felt that, whatever it might be, I had to do what my teacher had challenged me to do.

Later on that day, I went to the bedroom I shared with my little sister, Mary Katherine, and shut the door. I went into the bathroom and locked it. On the other side of the bathroom was a walk-in closet. I went into the closet and shut that door too. I have three younger brothers, a younger sister, and one brother who is a year and a half older than me. With six kids, our house was always chaotic. Full of life and voices. But there, in the closet, I was as alone as anyone could be in a home with eight people.