My Story (5 page)

Authors: Elizabeth J. Hauser

I

A MONOPOLIST IN THE MAKING

I

WAS

born at Blue Spring near Georgetown, Kentucky, July 18, 1854. My father, Albert W. Johnson, and my mother, Helen Loftin, met while attending different schools at the latter place and here they had been married August 4, 1853.

My mother was born in Jackson, Tenn., the same little town from which my fellow disturber of the public service peace, Judge Ben B. Lindsey of Denver, came.

My earliest recollections are of events connected with the war, though an incident which happened the year before seems very clear in my mind. Just how much of it I actually remember, however, and how much of it is due to hearing it often repeated I cannot say. But what happened was this: Joe Pilcher and I were playing on the floor with a Noah's Ark and a most wonderful array of little painted animals. These toys were made by the prisoners in the penitentiary at Nashville, where my mother had purchased them for me on our way South to our summer home, a plantation in Arkansas. After infinite pains and hours of labor my playmate and I had arranged the little figures in pairs, according to size, beginning

with the elephants and ending with the beetles, when one of the young ladies of our household, dressed for a party, crossed the room and with her train switched the lines to hopeless entanglement in the meshes of the long lace curtains, two of the animals only remaining standing. Joe, who was somewhat my senior, burst into tears, while I smiled brightly and said:

“Don't cry, Joe; there are two left anyhow.”

My mother never tired of telling this story and its frequent repetition certainly had a marked influence upon my life, for it established for me, in the family, a reputation as an optimist which I felt in honor bound to live up to somehow. I early acquired a kind of habit of making the best of whatever happened.

In later life larger things presented themselves to me in exactly the same way. Nothing was ever entirely lost. There was no disaster so great that there weren't always “two left anyhow.” My reputation for being always cheerful in defeat â a reputation earned at such cost that I may mention it without apology â is largely due to this incident, trivial though it may seem.

I remember the beginning of the war very well and am sure that from this time my recollections are actual memories, not family traditions.

As his first service to the Confederacy my father, a slave owner and cotton planter, organized a military company at Helena, Ark., of which he was Captain. Becoming Colonel in command of a brigade under General T. C. Hindman a little later, one of his first duties was to execute the order to destroy all cotton likely to fall into the hands of the enemy. Though he was opposed to this policy he enforced the order with rigid impartiality, compelling

my mother, who had managed to hide some cotton in the cane-brake, to bring it out and have it burned as soon as he discovered her secret. The burning of this cotton made a great impression on my mind, especially the sorrow of the negroes who stood around the smouldering bales and cried like children at sight of the waste of what had cost them such hard work to raise.

Shortly after this we moved to Little Rock and it was while we were living there that my mother shot a burglar who was trying to get into the house through a bedroom window. I recall this incident vividly. I can see the bed which my mother and the baby, Albert, occupied â with its white mosquito bar cover â in one corner of the room; against the opposite wall the bed in which my brother Will and I slept; the form of a man trying to climb through the window, and my mother's upraised arm as she discharged a pistol at him. She didn't hurt him much, but when he was captured in a similar attempt a few weeks later, the burglar admitted that he had gotten the wound in his leg from Mrs. Johnson.

My mother was not only courageous and self-reliant, but remarkably independent in thought and in action. She cared so little for what people might think or say that having made a decision she acted upon it without further ado. If my own disregard of the things “they say” is an inheritance from my mother I am more grateful for it than for any other characteristic she may have given me. With all her independence, however, she was one of the most tactful persons I have ever known. She had a genius for getting on well with people even under the most trying circumstances.

The stirring events of her young wifehood and mother-hood

afforded plenty of outlet for her energy, and in later and calmer times she found new means of expression. She studied French and music after she was forty, and she remodeled and built so many houses just for the enjoyment she got out of the planning that house building became almost a steady occupation with her.

General Hindman and my father quarreled over a court martial. Some young soldiers had stolen away one night and visited their homes in the vicinity of the camp. They were brought back and charged with desertion. Father insisted that they were not deserters, that they were just homesick boys who would have returned of their own free will, and he refused to conduct the trial on that account. Because of this quarrel he left Hindman to join General John C. Breckinridge's command near Atlanta.

In two light wagons and a barouche the family and several servants, old Uncle Adam standing out most clearly in my memory, started on that journey. We crossed the Mississippi river at Napoleon and just as we landed on the Mississippi side a Yankee gunboat came into sight. If we had been a few minutes later, or the gunboat a few minutes earlier, my father undoubtedly would have been taken prisoner. We went to Yazoo City, thence in our vehicles across the State of Alabama, arriving at Atlanta by Christmas â the first Christmas of the war.

I do not remember just how long we stayed in Georgia, but certainly more than a year, and most of that time at Milledgeville. One morning, much to my delight, I was permitted to hold in my arms the one-day-old son of the family with whom we were boarding. That baby is now William Gibbs McAdoo, famous for his successful promotion of New York City's underground railways.

When we left Georgia, we went north, through the Carolinas â most of the way by our own conveyances â to Corner Springs, Virginia, and later to Withville. While living at the former place I often saw detachments of Southern troops march by our house in the morning, and companies of Union soldiers pass in the afternoon of the same day. At Withville I had a terrible attack of typhoid fever, the first illness of my life. From Withville we went to Natural Bridge, where we spent a year or so, leaving here for Staunton just at the close of the war.

Though my father had served in the Confederate Army throughout the whole of the conflict he was a great admirer of Lincoln and very much opposed to slavery, and many, many times, even while sectional feeling was most bitter, he told me that the South was fighting for an unjust cause. My own hatred of slavery in all forms is doubtless due to that early teaching which was the more effective because of the dramatic incidents connected with it. Father's sympathies were with the North but loyalty to friends, neighbors and a host of relatives who were heart and soul with the South kept him on that side. Like so many of these he was now penniless, and I having attained the advanced age of eleven years commenced to look for something to do.

Immediately after Lee's surrender one railroad train a day commenced to run into Staunton, and I struck up a friendship with the conductor which was to prove not only immediately profitable to me, but which probably decided my future career. One day he said to me,

“How would you like to sell papers, Tom? I could bring 'em in for you on my train and I wouldn't carry

any for anybody else, so you could charge whatever you pleased.”

The exciting events attending the end of the war naturally created a brisk demand for news and I eagerly seized this opportunity to get into business. The Richmond and Petersburg papers I retailed at fifteen cents each and for “picture papers,” the illustrated weeklies, I got twenty-five cents each. My monopoly lasted five weeks. Then it was abruptly ended by a change in the management of the railroad which meant also a change of conductors.

The eighty-eight dollars in silver which this venture netted me was the first good money our family had seen since the beginning of the war, and it carried us from Staunton, Virginia, to Louisville, Kentucky, where my father hoped to make a new start in life among his friends and relatives.

The lesson of privilege taught me by that brief experience was one I never forgot, for in all my subsequent business arrangements I sought enterprises in which there was little or no competition. In short, I was always on the lookout for somebody or something which would stand in the same relation to me that my friend, the conductor, had.

Up to this time I had had practically no schooling, though my mother had managed to give me some instruction. Mathematics came to me without any effort whatever, this aptitude for figures evidently being an inheritance from my father and grandfather. My turn for mechanics came to me from my mother. She taught me to sew on the sewing-machine and I remember my great pride in a dress skirt which I tucked for her from top to bottom.

Our migrating days were not yet over, for being able to borrow some money in Louisville my father took us all back to Arkansas where he attempted to operate the cotton plantation with free labor. The experiment was a complete failure, a disastrous flood being one of the contributing causes.

Our next move was to Evansville, Indiana, where my father engaged in various enterprises and where I got my one and only full year of schooling. I passed through three grades in that year and was ready to enter High School when we again moved back to Kentucky â this time to a farm some eighteen miles from Louisville.

We were extremely poor and sending me to school in town was out of the question. I do not recall that our poverty or my lack of educational advantages had any depressing influence upon me. What helped most to make up for my meager schooling was my habit of observation and my investigating turn of mind â not to call it curiosity. I went about with an eternal Why? upon my lips. It was this doubtless which made life so interesting that I wasn't greatly impressed by the material condition of the family; also I had no silly theories about work and no so-called family pride to deter me from doing anything that came my way to do.

It never disturbed me in the least to sweep out an office and I liked the extra five dollars a month which this job paid me. It did surprise me very much, however, when some of my well-to-do friends and relatives would drive by and appear not to see me when I had charge of a gang of laborers in the street. My father and mother were quite as free from any class feeling as I was.

One of my jobs in Louisville was in the office of a

rolling-mill. When my mother went in to see about getting this job for me she had to wear a crocheted hood because she had no money with which to buy a hat or a bonnet. I spent more of my time in the mechanical department of the mill than in the office for it was that end of the business which interested me most.

Young as I was, I soon realized that this kind of enterprise offered no particular advantage. There was no conductor here to hand out something which wasn't his to give, and a few months later I welcomed an opportunity to get into the street railroad business in which I was to continue for most of my life. This appealed to me as a non-competitive business, depending upon the special privilege of public grants in the highway, though I did not analyze it at that time. The public side of the question meant nothing to me, of course; in fact it never occurred to me that there

was

a public side to it until I became familiar with Henry George's philosophy a good many years later.

I remember how offended I was when I first read his fascinating words and realized that the things I was doing were the things this man was attacking. Attracted to his teachings against my will I tried to find a way of escape. I didn't want to accept them; I wanted to prove them false. But this is running ahead of my story.

THE MONOPOLIST MADE

I

T

was the first of February, 1869, that I went to Louisville to take my job in the rolling-mill and it was at about this time that Bidermann and Alfred V. du Pont bought a street railroad in Louisville. These brothers were grandsons of Pierre Samuel du Pont, one of the physiocratic economists of France, associate of Turgot, Mirabeau, Quesnay and Condorcet to which group “and their fellows” Henry George inscribed his

Protection or Free Trade

, calling them “those illustrious Frenchmen of a century ago who in the night of despotism foresaw the glories of the coming day.” Pierre du Pont, after narrowly escaping the guillotine, came to this country during the Reign of Terror and established on the Brandywine the du Pont powder works known as the E. I. du Pont de Nemours Powder Company, the concern that now manufactures practically all the high explosives in the United States.

The du Ponts were friends of our family and gave me an office job in connection with their newly-acquired street railroad. I lived with the family of my uncle Captain Thomas Coleman in Louisville and a lively family it was with its nine daughters and two sons. Though these girls were my cousins and I was but fifteen years old I fell in love with one after another of them until I had been in love with all except the few who were either too old or

too young. The associations of this home and the influence of that splendid woman, my aunt Dullie Coleman, and her daughters saved me from the temptations that ordinarily beset the country boy in the city.

My salary was seven dollars a week and my duties were varied. I collected and counted the money which had been deposited by the passengers in the fare-boxes, made up small packages of change for the drivers (the cars had no conductors), and in a short time took entire charge of the office as bookkeeper and cashier. I sat up until eleven o'clock every night for a month learning to “keep books.” At the end of that time a trial balance had no terrors for me.

This was of course before the introduction of electricity in street railway operation and the cars were drawn by mules. How I hated to see horses and mules go into the street car service where they would be ground up as inevitably, if not quite as literally, as if put through a sausage machine! It was this feeling of pity for the defenseless creatures that first interested me in cables and electric propulsion.

From the very first it was the operating end of the business that appealed to me. My liking for mechanics was stimulated by my environment and I was soon working on inventions, some of which I afterwards patented. From one of these, a fare-box, I eventually made the twenty or thirty thousand dollars which gave me my first claim to being a capitalist.

The fare-boxes in use up to that time were made for paper money. Mine was the first box for coins, paper currency having just been withdrawn from circulation. It held the coins on little glass shelves and in plain sight

until they had been counted. Since any passenger as well as anyone acting as a spotter could count the money there wasn't much likelihood that either the drivers or the car riders would cheat. This box is still in use.

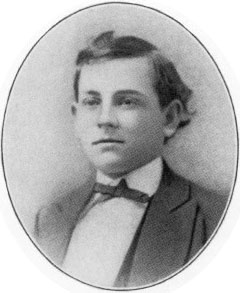

TOM L. JOHNSON AT SEVENTEEN

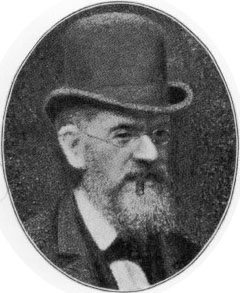

A. V. DU PONT

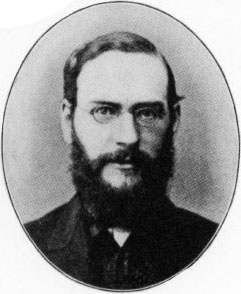

BIDERMANN DU PONT

In a few months I was secretary of the company, and at about the end of my first year of employment my father came in from the farm and the du Ponts made him superintendent of the road. He continued in this position until he was appointed chief of police of Louisville, several years later. Then I became superintendent, holding the job until 1876 when I embarked in business for myself.

I may say, with all propriety, that Bidermann du Pont, the president of the road, found in me a hard working and efficient assistant, but I cannot say that I never occasioned him any anxiety, for my restless, eager nature was constantly seeking ways of expression â which ways were not always either dignified or safe. For instance, one night when a lot of our cars were lined up on Crown Hill, waiting to carry the crowds home from a late entertainment in a summer garden, I challenged the drivers to join me in taking one of the cars down the hill as fast as it would go. The plan was â to start a car with as much speed as the mule team could summon, when it was fairly started the driver to drop off with the team, the rest of us to stay on for no reason in the world except to see “just how fast she would go.” The drivers weren't very keen to accept my challenge, but finally four of them decided to do so. After several starts we got up a rate of speed rapid enough to suit us and away we went. As the car tore madly down the hill I recalled the railroad track at the bottom and the curve in our track just beyond but there really wasn't time to think about what might

happen if the car and a train should reach the crossing at the same instant; for just then we shot over the railroad track, hit the curve which didn't divert the car from its straight course, and landed half-way through a candy-shop. The company paid damages to the shop-keeper, and what Mr. du Pont thought of the episode I never knew for even after the matter had been adjusted he never mentioned it to me.

A little while after this when there were some new mules in the stables waiting to be trained to car work, I decided to hitch the most refractory and unpromising team to a buggy and “break them in.” A little driver named Snapper joined me in this enterprise. With much difficulty, and the assistance of some dozen darkeys, we got the mules into harness and hooked up to an old, high-seated buggy. I had the reins, Snapper took his place on the seat beside me and we were off. It wasn't long before I knew to a dead certainty that those mules were running away.

We had a clear stretch of road before us, however, and I reflected that they'd have to stop sometime and trusted to luck that we'd be able to hang on until they did. But presently, just ahead of us, there appeared a great, covered wagon, with a fat, sun-bonneted German woman on the seat driving. She was jogging along at a comfortable pace, all unconscious of the cyclone which was approaching from behind. To get around her wagon was impossible, but here was my chance to stop our runaway! I steered the mules straight for the wagon, one on one side, one on the other, and the pole of the buggy caught the wagon box fairly in the middle. In the mix-up Snapper and I fell out, the mules dashed on with some remnants

of the wreck still attached to them, and the old lady was the most surprised individual you ever saw in your life. She wasn't hurt, and neither were we, nor was the wagon much harmed.

The president of the road was as silent on this foolhardy adventure as he had been on the candy-shop scrape, but Mr. Alfred du Pont took me severely to task for it, saying that while he did not object to my breaking mules he did object most seriously to having me break my neck.

I had not been in the street railroad business long before I determined to become an owner. I didn't want to work on a salary any longer than I could help. My fondness for girls in general and girl cousins in particular culminated in my marriage, October 8, 1874, to a distant kinswoman of my own name, Maggie J. Johnson, when she was seventeen and I was twenty. At twenty-two I purchased the majority of the stock of the street railways of Indianapolis from William H. English, afterwards candidate for vice-president of the United States in the Garfield-Arthur and Hancock-English campaign.

I went to Indianapolis to see Mr. English in the hope of interesting him in my fare-box. He said to me,

“I don't want to buy a fare-box, young man, but I have a street railroad to sell.”

My business dealings with him were so unpleasant and the charges which my lawyer (afterwards Governor Porter of Indiana) brought against him in a law suit so severe, that the petition embodying them was used by his Republican opponents as a campaign document. That fight with Mr. English was my first great business struggle, and it was a fight for a privilege â for street railway grants in the city of Indianapolis.

I had some money, but not enough for my purchase. Mr. Bidermann du Pont, though he had no faith in my business associates and though the road was in a badly demoralized state, loaned me the thirty thousand dollars I needed with no security whatever except my health, as he himself expressed it. That loan meant a lot to me, but the confidence which went with it meant more, for Mr. du Pont was the first business man to give me any encouragement.

When I made my final payment to him some five or six years later I told him that my money obligation was now cancelled, but that a life-time of friendship for him and his could not discharge my greater obligation for his faith in me.

My father went with me to Indianapolis and became president of the company. When a friend asked him:

“If you are president of the road, what is Tom?” he replied, “Oh, Tom's nothing! He's just the board of directors.”

As this board of directors, I speedily realized that our enterprise would be a failure unless we could free ourselves from Mr. English's persecutions. He was old enough to be my father, and his attitude towards me was arrogant. He was the most influential man in Indianapolis and not above threatening us with his power over the city government unless we coöperated with him in every way, especially in getting tenants for his houses of which he owned about two hundred, and which he rented to employes of our road and to other workingmen.

Mr. English was a typical representative of the powerful agent of special privilege of that day. He was president of one of the principal banks of the city.

The people's money goes into the banks in the form of deposits. The banker uses this money to capitalize public service corporations which are operated for private profit instead of for the benefit of the people. How incongruous that the people's own savings should be used by Privilege to oppress them!

Mr. English's great asset was his domination of the local city government through which he controlled the taxing machinery of the city, thereby keeping his own taxes down at the expense of the small tax-payer.

When I bought into the railroad he turned the office of treasurer over to me as his successor and at the first meeting of the board of directors we passed resolutions stating that his accounts had been audited and giving him a receipt for his stewardship. When I objected to this because I had not seen the books he said it was a mere matter of form and that he would turn them over to me immediately after the meeting. It was eleven months before I ever got a look at those books and then my right to them had been established by a lawsuit. After going through the books I forced Mr. English to make several restitutions of very large amounts of money to the company. Once we had a disastrous fire and he immediately notified the insurance companies that the damages must be paid to him. We had to consent to this or expose ourselves to expensive and annoying litigation.

He kept us in constant hot water. We had paid ten per cent. of the purchase price in cash and given notes running through a period of ten years for the remaining ninety per cent. His reason for selling to us in the first place seems to have been to rid himself of some partners whom he did not like. He evidently expected to make

us very sick of our bargain, to benefit by whatever payments we made and finally to get the property back into his own hands unencumbered by undesirable partners.