My Story (28 page)

Authors: Elizabeth J. Hauser

This is the kind of “educational campaign” the Concon was conducting through paid advertisements in the newspapers, the

Press

alone declining to print them, when the “financial interest” suit was on in the courts. They managed to bring the case before a pliant judge and a very stupid man withal, and they got from him the desired decision. Later, after a full hearing before a reasonable judge, this foolish verdict was set aside, but it had served its purpose of delaying the extension of the three-cent fare lines and seriously embarrassing the Forest City Railway.

When the Forest City Company found itself confronted with the probability of having all its grants declared invalid because of the “personal interest” claim they were forced to decide quickly what move to make next in order to retain the advantage the city had so far gained over the old monopoly company. It was at this juncture that the Low Fare Railway Company came into being. It was incorporated by W. B. Colver and others and financed by a man who believed in our movement and who was not a resident of Cleveland. It started free from the claim of personal interest.

The Low Fare Company bore the same relation to the

Municipal Traction Company that the Forest City did. The low-fare companies were eager to push ahead and extend their range of operations eastward on Central avenue, but while the question of this franchise was in the United States Supreme Court no move could be made. At the hearing before this court the Concon was represented by Judge Warrington, already mentioned, and by Judge Sanders of Squire, Sanders and Dempsey, the Concon's local attorneys. The interests of the city and of the low-fare line were in the hands of City Solicitor Baker and D. C. Westenhaver, who had lately come to Cleveland from West Virginia and become a partner in the firm of Howe & Westenhaver. He did most of the fighting for the low-fare companies. All the big lawyers, those of established reputation, were employed by the other side or so tied up that they couldn't accept cases for the three-cent-fare crowd â except Mr. Baker, of course, whose public employment kept him on the city's side. Privilege certainly had a powerful influence with some judges and it did its best to monopolize the best legal talent available. The odds against us in the whole long fight were so great that perhaps we couldn't have gone on as we did year after year, hopefully, cheerfully â even getting a lot of fun out of it, as we certainly did â if we had been able to look ahead and foresee the obstacles and count the cost. And yet I think we should have gone on just the same.

The Low Fare Company had been granted rights for a through route from east to west on East Fourteenth street, Euclid avenue, the Public Square, Superior avenue, the viaduct, West Twenty-eighth street and Detroit avenue.

All the low-fare grants, both of the Low Fare Company and the Forest City, were made to expire at about the same time, twenty years from the date of the original Forest City grant, September 9, 1923.

The New Year found the city nearer three-cent fare than it had been at any time during the six years of the fight and on January 7 the low-fare people were made very happy by the decision of the United States Supreme Court in the Central avenue case, which confirmed Judge Tayler's decision that the franchise of the Cleveland Electric Street Railway Company on Central avenue, Quincy avenue and East Ninth street had expired in 1905. The news came to us in Judge Babcock's court, where the Sumner avenue injunction suit was being heard. Mr. du Pont left the court room and hurried to the offices of the Cleveland Electric, where he found two or three of the company's directors who had not yet heard of the decision. Several other directors came in before he left and he proposed that an agreement be effected whereby the injunction against the Forest City on Detroit avenue be held in abeyance, the low-fare people on the other hand doing nothing to interfere with the Cleveland Electric's cars on Central avenue, which were to be operated at a three-cent fare. If either side wished to terminate this agreement twenty-four hours' notice was to be given.

The Sumner avenue grant to the Low Fare Company was declared legal on January 9, so the people won another important victory.

Cleveland Electric stock went down to sixty after the United States Supreme Court decision in the Central avenue case, and immediately thereafter the old company came to the council seeking some kind of a settlement.

Somehow all the disagreeable litigation didn't seem to prejudice the car-riders, for the low-fare lines were exceedingly popular from the very start â much too popular for the comfort of the old company in spite of everything that had been done to make the project fail.

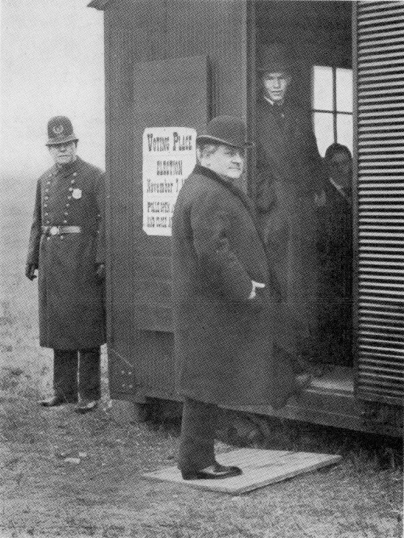

Photo by L. Van Oeyen

Tom L. Johnson entering voting booth, November 7, 1906

AFTER SIX YEARS OF WAR

T

HE

New Year (1907) found the city in a stronger position than it had been at any time since the beginning of the fight. Immediately after the United States Supreme Court decision in the Central avenue case, the Municipal Traction Company and the Cleveland Electric entered into a thirty-day truce, each side agreeing not to resort to litigation while the truce was operative, the Concon to be permitted to run without interruption on Central and Quincy avenues and the Threefer to be unmolested in operating from its western terminal up to and around the Public Square.

On the twelfth day of January, then, the first three-cent-fare car ran to the Public Square. It had taken two and a half years to get the grant for that car to run to the Square, and nearly four and a half years from the time the grant was made for it to wade its way through injunctions to that point. This shows Privilege's power to delay anything which is against its interest, and illustrates the persistence of our movement to hold on under all difficulties. The agreement permitting the opening of the line to the Square was carried out as soon as it was made, and before the public had a chance to be informed of it. The appearance of three-cent cars on the East side of the viaduct was a signal for enthusiastic demonstrations by pedestrians and car riders. Women waved their

handkerchiefs towards it as if it were a personal friend and ever so many humorous incidents occurred on the cars. Everybody seemed happy and friendly and every-thing seemed to point to a peaceful settlement and a speedy victory.

Photo by L. Van Oeyen

1. A. B. DU PONT. 2. MAYOR JOHNSON. 3. VICE MAYOR LAPP. 4. MAYOR'S SECRETARY, W. B. GONGWER. 5. PETER WITT. 6. FREDERIC C. HOWE.

“It had taken two and a half years to get the grant for that car to run to the Square, and nearly four and a half years ⦠for it to wade its way through injunctions to that point.”

Enough has been told in detail to show how the fight was waged. It is not necessary to follow each of the low-fare companies in the matter of the grants made to them, nor into the courts to trace the trail of each injunction. The people of Cleveland had been patient, law-abiding and long-suffering to a remarkable degree, and when the old company and the Municipal Traction Company, pursuant to the request of the former and a resolution of the city council, commenced to negotiate a settlement there was general satisfaction.

Before the truce was six days old it developed that the Concon was violating it by going after property owners' consents and revocations on Rhodes and Denison avenues, but when President du Pont called the attention of President Andrews to this the latter ordered all consent operations stopped. It was hoped that settlement would come by means of the holding company plan â that the Cleveland Electric would lease its lines to the Municipal Traction Company, which was in position to take them over at a just rental value and to continue the operation of all cars in the interest of the community. These negotiations were conducted by Presidents Andrews and du Pont. They continued through January, through February and on until late in March. Every few days the newspapers would announce that a final settlement was about to be reached, and then again that negotiations had been broken off. At last on March 25 each side presented a statement

to the city council. They had been unable to agree upon the valuation of the Cleveland Electric property. The figures presented were as follows:

ANDREWS'S VALUATION

.

| Total physical and franchise values....................... | $30,500,000.00 |

| Added one-ninth, per agreement............................ | 3,388,888.88 |

| _________________ | |

Grand total....................................................... | $33,888,888.88 |

| Funded and unfunded debt deducted..................... | 9,341,000.00 |

| _________________ | |

Net valuation................................................... | $24,547,888.88 |

| Stock value, per share, this valuation..................... | 105.00 |

DU PONT'S VALUATION

.

Total physical and franchise value.......................... | $17,908,314.24 |

Added one-ninth, per agreement.............................. | 1,989,812.69 |

| _________________ | |

Grand total ........................................................ | $19,898,126.93 |

| Outstanding stock, per share................................... | 45.10 |

| Redeemable on suggested plan................................ | 49.61 |

Far apart as these figures were I did not feel that they precluded a settlement. One of the daily newspapers asked me to sum up the situation and this is what I said:

“You ask me to sum up for you the street railway situation as it exists to-day.

To begin with let us eliminate one or two things that may be in the public mind through misapprehension.

Mr. Andrews has not offered to lease his road on a basis of $105 per share.

Mr. du Pont has not offered to lease on a basis of $49.61.

Mr. Andrews has said that he can figure out a value of $105

per share, but we are not informed what are the factors or processes in his calculation.

Mr. du Pont says that he can figure out $49.61 per share, and that that figure is a cold, hard trading figure, containing only about 21 per cent. good will or bonus-for-peace factor. Let du Pont tell how he arrived at his figures.

The situation to-day then is: How far ought Andrews to come down, and how far ought du Pont to come up?

If each man will give his processes as to each disputed item, these disputes ought to be settled singly and without great trouble. That is what the council is now trying to get at. Progress along such lines means progress toward a complete, satisfactory and comprehensive settlement. I believe that the Cleveland Electric Railway Company, as well as others concerned, desire such a settlement.

Now let us proceed carefully, without undue delay, and also without undue haste. The public interest â for the first time in years â is not suffering by reasonable delay. We have lowered fares all over the city, and each of the two companies, one a public one and one a private one, is vying with the other to earn and keep public favor. So there is no public clamor for a settlement to be marred by haste, though we all agree that not a minute of unnecessary delay should be tolerated. The sooner the three-cent rate comes to everybody the better.

There is one danger just now. It will be to the advantage of certain interests to start a hullaballoo over some side issue so that the main point may be obscured. This is the old tactics and we can expect it again. This time the side issue will be as to rates of fare in the suburbs. Let us meet that, settle it and dispose of it so that we can give our undivided attention to the main question.

First, ninety people ride in the city to every ten outside.

Second, the people of Cleveland and their council are not the guardians of the suburbs.

Third, the suburbs, in times past, nearly all of them, against

advice and protest, have, through their councils, made long-time grants to the Cleveland Electric railway.

Fourth, each dollar of revenue cut off from a long-time suburban grant must be made up in added generosity in grants by the city of Cleveland.

Now, then, this is what I propose, that three-cent fare in Cleveland for the benefit of the ninety must not be imperiled for the sake of the ten who have bargained and granted away their chances to make contracts for themselves.

If the suburban people made twenty-five year contracts they are bound just as the people and council of Cleveland are bound by existing franchise grants.

But the suburban people must be treated just as generously and fairly as possible. I should not expect to charge five cents if service could be rendered in a given suburb for four cents. I would not charge four if the service could be given at three or three and a half.

Let us have three-cent fare and universal transfers in the city, and, with open books, agree to serve each suburb at exact cost of service. Take this in its broadest sense when I say “at cost.” Let all the profit be made in the city at the three-cent fare, and simply charge the fare in the suburbs that will meet actual cost of operation and interest on physical property. Figure it just as closely as possible and have the books open to the people and officials of each suburb, so that they may know they are getting their service at cost â and that is relatively even cheaper than the cost to the people of Cleveland themselves. I think no honest man could ask more. Let us proceed to seek a fair, equitable settlement and let us not be sidetracked on a ten per cent. question, so as to lose sight of the ninety per cent. question.

As to arbitration: I believe that is just what is going on now. The council is now sitting as a board of arbitration, seeking to learn what the exact differences are between Mr. du Pont and Mr. Andrews. If each of these men will be frank and free to explain his figures and processes, their differences will be brought

out so plainly that adjustment will not be difficult. I think the arbitration now in progress will meet all needs.”

All street railroad conferences had been public for a long time and these were generally well attended. When any new question came up there was always an increased attendance, and the council meetings following the report just referred to were in effect town meetings.

The special street railway committee of council presented a report recommending the holding company plan on a basis of sixty dollars a share for Concon stock, which report was adopted by council, April 2, by a vote of twenty-nine to one. On April 4 the

Plain Dealer

announced in large head lines, “Directors of Cleveland Electric Will Accept Offer of Council if Three-Cent Fare is Assured,” and said:

“The directors of the Cleveland Electric Railway Company, at a meeting at the Union Club yesterday afternoon, adopted a resolution covering all the points to be made in the reply of the company to the council offer of sixty dollars per share for Cleveland Electric stock on the holding company basis.

The communication is to be drawn up to-day and submitted to the board for final approval at another meeting⦠. The communication will then be ready for council and it is expected that a special meeting will be called for Friday, when the reply of the company will be formally submitted. President Andrews refused to discuss the nature of the resolution ⦠but on authority of a leading interest in the company it is stated that the reply will be an acceptance of the holding plan at the figure offered by the council committee. The acceptance will be in the form of a challenge to the mayor, and in such form that if the city accepts, it must either make good on the proposal to operate for three-cent fare within the city limits, and five-cent fare

outside, or the property will revert to the Cleveland Electric shareholders under a seven-for-a-quarter twenty-five year franchise.”

Council met on Friday morning to receive the Company's reply. In the meantime, on April 2, Mayor Dunne had been defeated for re-election in Chicago and his municipal ownership programme turned down. How much influence this had on the action of the directors of the Cleveland Electric we do not know, but it is certain that it gave them hope that what had been accomplished in Chicago might be accomplished in Cleveland. The whole community was interested in the negotiations and the lobby of the council chamber was crowded with eager spectators. I was presiding and called the meeting to order. City Solicitor Baker and City Clerk Witt sat back of me. President Andrews and his directors, most of whom were present, sat at my left. Back of these were the councilmen at their desks and back of the rail and crowding the gallery as many citizens as could squeeze in.

The Cleveland Electric's communication was handed to the city clerk to read, Secretary Davies of the Concon holding a copy of the statement and following it closely to see that the clerk read it correctly. A hasty glance over the document showed Witt its character. If, actuated by the bitterest hatred, he had drawn up that statement himself he could scarcely have read it more effectively. It was not only a refusal of the city's proposition and notice that the seven tickets for a quarter were to be immediately withdrawn and the old five-cent fare reestablished, but a most insulting attack on the mayor, the

city council, and the friends and promoters of the low-fare movement. As Witt read on, page after page of the document, which made more than a page of newspaper copy when in type, he fairly “acted out” the insinuations, the cruel charges, the arrogant assumptions of the signers of that statement. He was getting angrier every minute, but kept himself well in hand, and when he had finished I asked the pleasure of the council. A member moved that the statement be received and time given to consider it. I said that the communication was a flat refusal to accept the proposition, referred to the charges against the mayor and the council, saying that we should be able to take care of these, and concluded by saying, “This question will not be settled by personal attacks, but for the benefit of the people,” and asked if others wished to talk. Peter Witt was demanding the floor, as a citizen, but Mr. Baker spoke first. He said in part: