My Story (12 page)

Authors: Elizabeth J. Hauser

I reasoned that if I contended for free trade in this particular branch of industry with which I was so familiar and in which I was personally interested, it would clear the way for a similar fight on all other free trade amendments. It could not be charged that I was for free trade in every district but my own nor in every industry except the one in which I was myself engaged.

When I spoke of the steel-rail pool Mr. Dalzell surprised me by denying its existence. He said there

had been

a combination between certain steel rail men, which had been broken up by the refusal of a large number of firms to go into it, and that it had fallen of its own

weight but that there was no condition in it for keeping up prices, etc., etc., and that now this pool was no more. Mr. Dalzell was like that secretary of the interior of a later day who went out to investigate the beef trust and came back to Washington from Chicago with the statement that there was no beef trust. He had asked the Armours and they had said, “No.” And so Mr. Dalzell had asked the rail manufacturers whether there was a steel-rail pool and they had said, “No.”

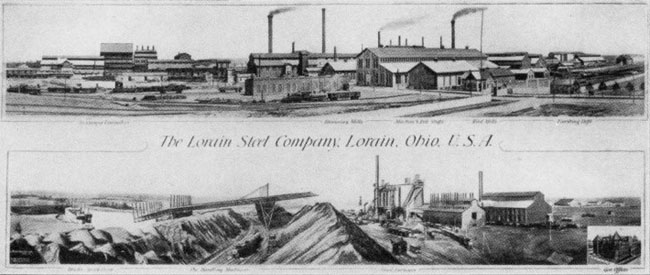

NOW THE NATIONAL TUBE COMPANY: BUILT BY MR. JOHNSON

For answer I picked up from my desk a paper which I said was a copy of an agreement proving the existence of the pool. Mr. Dalzell said he was bound to accept my statement, but that he deprecated trusts as much as I did. I retorted that as a business man I didn't deprecate trusts, I joined them,â but that as a member of Congress I neither represented nor defended them. I said that if it were true as our Republican members were urging that protection was a good thing for labor then Pittsburgh ought to be a very paradise for working men, but the actual fact was that a few days before Mr. Carnegie had sailed for Jerusalem he utilized the tariff to reestablish the steel-rail pool and pay other manufacturers to shut up their works and throw their men out of employment; then came a general cut in wages in all his great establishments; and

then

he announced himself ready

to give as much as five thousand dollars a day to feed the unemployed of Pittsburgh

. Privilege doesn't have to bribe congressmen when it can fool them.

Of course steel rails weren't put on the free list, and of course the steel-rail pool continued until the necessity for such combination was done away with, when the various

concerns represented in them passed into a common ownership.

This merging of various enterprises into one wasn't brought about so much by the necessity for protection against laws which forbade combinations in restraint of trade, as by the necessity for the mutual protection of the pool members against each other. It was a matter of common knowledge on the inside that their agreements were ruthlessly broken. I have known members of labor unions to starve to carry out

their agreements

.

While the Wilson bill was under consideration I received a letter from some Cleveland cloak manufacturers requesting me to vote for a specific duty in addition to an ad valorem duty on ladies' cloaks. The letter had been prepared by politicians and newspaper men for the express purpose of putting me in a hole with my constituents. They knew perfectly well that I wouldn't promise to vote for the duty, but they thought my answer would give them the opportunity they wanted of coming back at my free trade talk with a protectionist argument which would make me ridiculous. I learned that the big protectionists of my district were fairly hugging themselves in joyful anticipation of the sorry spectacle I would make. They were about to silence me forever in that district at least on the subject of free trade.

I explained the matter to Mr. George and he framed a letter in reply, which was given wide publicity as part of my speech on the Wilson bill. That letter was one of the finest pieces of writing Mr. George ever did, and if anything deserves a place in this story it does. It was as follows:

C

LEVELAND

, Ohio, Dec. 29, 1893.

To Joseph Lachnect, Emil Weisels, Joseph Frankel and others, tailors and tailoresses in the employ of Messrs. Landesman, Hirscheimer & Co., cloak manufacturers of Cleveland.

Ladies and Gentlemen:

I have received your communication and that from Messrs. Landesman, Hirscheimer & Co., to which you refer, asking me to vote against the Wilson tariff bill, unless it is amended by adding to the duty of 45 per cent. ad valorem, which it proposes, an additional duty of 49½ cents per pound.

I shall do nothing of the kind. My objection to the Wilson bill is not that its duties are too low, but that they are too high. I will do all I can to cut its duties down, but I will strenuously oppose putting them up. You ask me to vote to make cloaks artificially dear. How can I do that without making it harder for those who need cloaks to get cloaks? Even if this would benefit you, would it not injure others? There are many cloak-makers in Cleveland, it is true, but they are few as compared with the cloak-users. Would you consider me an honest representative if I would thus consent to injure the many for the benefit of the few, even though the few in this case were yourselves?

And you ask me to demand, in addition to a monstrous ad valorem duty of 45 per cent., a still more monstrous weight duty of 49½ cents a pound â a weight duty that will make the poorest sewing-girl pay as much tax on her cheap shoddy cloak as Mrs. Astor or Mrs. Vanderbilt would be called on to pay on a cloak of the finest velvets and embroideries! Do you really want me to vote to thus put the burden of taxation on the poor while letting the rich escape? Whether you want me to or not, I will not do it.

That, as your employers say, a serviceable cloak can be bought in Berlin at $1.20 affords no reason in my mind for keeping up the tariff. On the contrary, it is the strongest reason for abolishing it altogether. There are lots of women in this country who would be rejoiced to get cloaks so cheaply; lots of women who must

now pinch and strain to get a cloak; lots of women who cannot now afford to buy cloaks, and must wear old or cast-off garments or shiver with cold. Is it not common justice that we should abolish every tax that makes it harder for them to clothe themselves?

No; I will do nothing to keep up duties. I will do everything I can to cut them down. I do not believe in taxing one citizen for the purpose of enriching another citizen. You elected me on my declaration that I was opposed to protection, believing it but a scheme for enabling the few to rob the many, and that I was opposed even to a tariff for revenue, believing that the only just way of raising revenues is by the single tax upon land values. So long as I continue to represent you in Congress I shall act on the principle of equal rights to all and special privileges to none, and whenever I can abolish any of the taxes that are now levied on labor or the products of labor I will do it, and where I cannot abolish I will do my best to reduce. When you get tired of that you can elect someone in my place who suits you better. If you want duties kept up, you may get an honest protectionist who will serve you; you cannot get an honest free trader.

But I believe that you have only to think of the matter to see that in adhering to principle I will be acting for the best interests of all working men and women, yourselves among the number. This demand for protective duties for the benefit of the American working man is the veriest sham. You cannot protect labor by putting import duties on goods. Protection makes it harder for the masses of our people to live. It may increase the profits of favored capitalists; it may build up trusts and create great fortunes, but it cannot raise wages. You know for yourselves that what your employers pay you in wages does not depend on what any tariff may enable them to make, but on what they can get others to take your places for.

You have to stand the competition of the labor market. Why, then, should you try to shut yourselves out from the advantages that the competition of the goods market should give you? It is

not protection that makes wages higher here than in Germany. They were higher here before we had any protection, and in the saturnalia of protection that has reigned here for some years past you have seen wages go down, until the country is now crowded with tramps and hundreds of thousands of men are now supported by charity. What made wages higher than in Germany is the freer access to land, the natural means of all production, and as that is closed up and monopoly sets in wages must decline. What labor needs is not protection, but justice; not legalized restrictions which permit one set of men to tax their fellows, but the free opportunity for all for the exertion of their own powers. The real struggle for the rights of labor and for those fair wages that consist in the full earnings of labor is the struggle for freedom and against monopolies and restrictions; and in the effort to cut down protection it is timidly beginning. I shall support the Wilson bill with all my ability and all my strength.

Yours very respectfully,                 Â

T

OM L. JOHNSON

.   Â

Day after day passed. No answer came from Cleveland. It was my turn to be amused now for the reply never did come.

One of the principal movers in the matter, an experienced newspaper man connected with the leading Republican daily in my district, told me some time afterwards that he had wasted reams of paper and burned much midnight oil in a fruitless attempt to answer. “But,” said he, “I'm just as much a protectionist as ever only it won't work on ladies' cloaks.”

SOME PERSONAL INCIDENTS AND STRAY OBSERVATIONS

C

HANCE

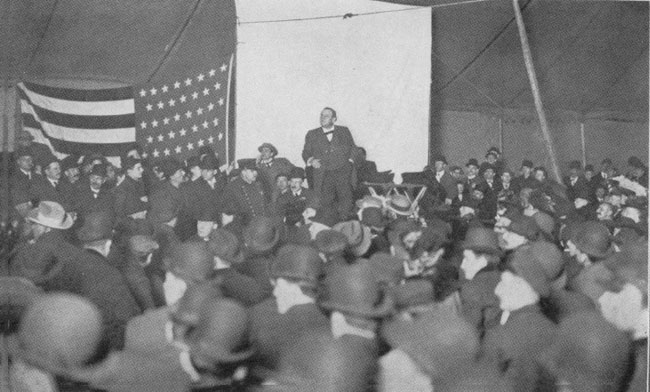

was responsible for my tent meeting campaigning. Once in one of my early Congressional campaigns when I wanted to have a meeting in the eighteenth ward in Cleveland there was no hall to be had. A traveling showman had a small tent pitched on a vacant lot and someone suggested that it might be utilized. It had no chairs but there were a few boxes which could be used as seats. Very doubtful of the result we made the experiment. It cost me eighteen dollars, I remember. After that I rented tents from a tent man and finally bought one and then several.

The tent meeting has many advantages over the hall meeting. Both sides, I should say all sides, will go to tent meetings â while as rule only partisans go to halls. Women did not go to political meetings in halls in those days unless some especially distinguished person was advertised to speak, but they showed no reluctance about coming to tent meetings. In a tent there is a freedom from restraint that is seldom present in halls. The audience seems to feel that it has been invited there for the purpose of finding out the position of the various speakers. There is greater freedom in asking questions too, and this heckling is the most valuable form of political education. Tent meetings can be held in all parts of the city â in short the meetings are literally taken to the people.

It was not long after I got into municipal politics in Cleveland before the custom of tent meetings was employed in behalf of ward councilmen as well as for candidates on the general ticket, and they too were heckled and made to put themselves on record. The custom of heckling is the most healthy influence in politics. It makes candidates respect pre-election pledges, forces them to meet not only the opposition candidates but their constituents.

But the greatest benefit of the tent meeting, the one which cannot be measured, is the educational influence on the people who compose the audience. It makes them take an interest as nothing else could do, and educates them on local questions as no amount of reading, even of the fairest newspaper accounts, could do. I do not believe there is a city in the country where the electorate is so well informed upon local political questions, nor upon the rights of the people as opposed to the privileges of corporations, as it is in Cleveland. Detroit and Toledo probably come next. The tent meeting is largely responsible for this public enlightenment of the people of Cleveland.

The one disadvantage of the tent is that it is not weather-proof. And yet it was seldom indeed that a meeting had to be abandoned on account of rain. Great audiences came even on rainy nights and our speakers have frequently spoken from under dripping umbrellas to good-natured crowds, a few individuals among them protected by umbrellas but many sitting in the wet with strange indifference to physical discomfort.

At first my enemies called my tent a “circus menagerie” and no part of my political work has been so persistently cartooned; but when they employed tents somewhat later

they called theirs “canvas auditoriums.” The adoption of the tent meeting by these same enemies or their successors may not have been intended either as an endorsement of the method or as a compliment to my personal taste, but I can't help considering it a little of both.

In my 1894 canvass for Congress at the first meeting held in a new tent, an incident occurred which brought me into contact with one of the bravest and most resourceful fighters against special privilege that it has been my good fortune to know.

The meeting had proceeded only a few minutes when about a third of the audience set up a call for “Peter Witt,” and the name was cheered lustily two or three times.

I had never heard of Peter Witt, but ten minutes later in response to my customary invitation for questions an angry, earnest man, with flashing eyes and black locks hanging well down on one side of his forehead, rose in the center of the tent and shaking a long finger at me put a question in the most belligerent manner imaginable. I knew that the man the audience had been cheering for stood before me. I disregarded his question and asked with all the friendliness I could summon,

“Are you Mr. Witt?”

With scant civility he half-growled, half-grunted an affirmative answer, and I continued,

“Since you seem to have so many friends here, and in a spirit of fair play, I would be glad to share the platform with you. I do not like to see you at the disadvantage of having to speak from the audience.”

There were mingled shouts of “Come on, come on!” and “Speak where you are!” from the crowd, and the angry young man was literally forced to come forward.

The time consumed and the difficulty encountered in stumbling over camp chairs through the crowd and up onto the platform worked a change in Mr. Witt's manner. Fully half his steam had escaped and there wasn't much of his venom left when I grasped his hand. So little of kindness had come his way that he was not prepared for the warm reception and cordial introduction to the audience which I gave him.

Photo by L. Van Oeyen

“Chance was responsible for my tent meeting campaigning.”

Peter Witt was an iron molder by trade and the things he had suffered because of the brutalities of our industrial system had made him hate the system and long to free his fellow workers from its baneful power. His reward for his struggles, his sacrifices and his passionate devotion to the common good had been â to use one of his own expressionsâ“the blacklist of the criminal rich and the distrust of the ignorant poor.”

Believing the Populist party offered more hope of relief than any other political organization he had allied himself with it, and I afterwards learned that the demonstration in my tent meeting was a preconcerted plan on the part of the Populists to capture that meeting. They didn't capture the meeting, nor did we capture the Populist orator for not during that campaign did Witt let up in his fight against the Democratic ticket, nor would he admit any change of feeling towards me personally. But he has fought with me, not against me, in every campaign I have since been in, and one of the strongest friendships of my life commenced that night when I welcomed Peter Witt to my platform. His sphere of influence has widened since then, and also his circle of friends, for many men, at first repulsed by his seeming bitterness, coming later to understand his sterling qualities, his sturdy honesty,

his unswerving fidelity to principle, became his friends. Among them he may count some high priests of Privilege for these are human like the rest of us and being human they admire rugged honesty and genuine courage more than anything else in the world.

The year after I left Congress I got rid of my street railway properties in Cleveland and a brief history of the last days of my operations there is necessary to an intelligent understanding of the street railway war which occupied Cleveland's attention during most of my nine years as mayor.

In the latter part of March, 1893, the Everett road, the lines operated by the Andrews and Stanley interests and our company consolidated. In April of the same year Mr. Hanna took in the cable road. All the street railroads of the city were now in these two companies. The newpapers called the first the Big Consolidated, and the second the Little Consolidated which common parlance soon shortened to the Big Con and the Little Con; and when the Big Con and the Little Con consolidated ten years later, in 1903, the Concon was the result.

The Big Con controlled sixty per cent. of the business and the Little Con forty per cent. In the organization of the Big Consolidated I sided with the Andrews-Stanley crowd in electing Horace Andrews president of the company. The Everett interests would have liked to elect Henry Everett to that position. My brother Albert was a member of the board of directors of which I was chairman.

In the first days of the consolidation when we who had been fighting each other so long were in daily communication

and occupying the same offices a good many amusing things happened. Mr. Everett and a man who had been associated with him were having a quiet little meeting every day, for instance, and seemingly getting a great deal of pleasure out of some figures they were examining. By and by I became curious to know what these daily meetings were about and when I asked Mr. Everett he showed me with great glee figures which proved that their property had appreciated in value much more than mine since the consolidation. The increased earnings were coming from their lines, not ours. He was quite jubilant about it.

“Aren't all the companies sharing equally in the profits of consolidation?” I asked.

“Why, of course,” he answered.

“Then,” I said, “I don't see how you have got it on us any. Your lines are making the profits for the others. I guess I'll take your figures and show 'em to my people so they can see just how good a deal I made.”

That phase of the matter had actually never occurred to him. He didn't get any enjoyment out of comparative figures after that.

There was always a good deal of antagonism between Mr. Everett and me, and as we held the balance of power either of us could make the other uncomfortable by voting with the Andrews-Stanley crowd, as I did when I helped elect Mr. Andrews president, instead of voting for Mr. Everett.

Once the Everett interests planned as a joke that at the annual meeting they would see that my election as a director was made by a smaller vote than that given for any other officer. They thought it would be great fun

to let me in by the barest majority, thus making it appear that I was

persona non grata

on the board. Somehow the plan leaked out and I learned of it.

The day of the meeting came. I was on hand with my votes, about one-third of the whole number. When the votes were counted I had received more than anybody else.

When it dawned upon the other directors that I had cast all my votes for myself and none for anybody else, they made me pay for my fun by giving them a big dinner. I put up a dummy ticket too with Mr. Everett's name at the head and distributed a few of my votes on this ticket. The newspapers the next day in reporting the meeting said that “the Everett ticket was badly beaten” and it would have taken more than a dinner to appease the indignation this caused.

One day Mr. Hanna came to me and said, “Well, Tom, now that you've all consolidated, you and I might as well take up some old matters of dispute between us and get them settled.”

“Certainly!” I answered, “that's a good idea. By our consolidation agreement all disputes are to be referred to the president, so all you have to do is to see your friend Horace Andrews.”

Mark Hanna's methods were to those of Horace Andrews as quicksilver is to winter molasses. He knew it and he knew that I knew it. He gave me one look and delivered himself vigorously of two words by way of reply. I understood his language. I am quite sure those differences he spoke of haven't been adjusted to this day.

I sold all my Cleveland street railway interests in 1894 and 1895 and never afterwards had any pecuniary connection with street railroads in that city.