My Life So Far (94 page)

For me, religion is not so much about a belief in dogmas and traditions. It must be a spiritual

experience,

and I find it impossible to have that experience when I cannot reconcile myself to the Judeo-Christian assumption that man was God’s principal creation, with woman (Eve, fashioned from Adam’s rib) a mere derivative afterthought. Nor can I accept woman as the cause of man’s downfall, an assumption that has permitted men through the ages to regard women with suspicion and misogyny. (The best bumper sticker I ever saw read,

EVE GOT A BUM RAP.

) Women were anything

but

an afterthought for the Jesus I believe in. His acceptance of and friendship with women was truly revolutionary at a time when the male-dominated status quo had severed religion’s connection to the prepatriarchal ancient goddess and to nature. There was a reason why women were among Jesus’ most ardent followers: They responded to his revolutionary message of compassion, love, and

equality.

The outlawed Christian communities that spread into the desert to worship in secret after Jesus died included more women than men, by a margin of two to one. Women were among the early Roman Christians who met clandestinely in their homes, preached, converted men, and performed the Eucharist.

I am moved and inspired by those early Christians—like those in the Gospel of Thomas, the Secret Gospel of Mark, and the Book of John—who saw themselves as seekers more than believers; who felt that

experiencing

the divine was more important than mere

belief

in the divine. According to them, Jesus preached that each individual has the potential to

embody

God (embodiment again). Perhaps this is one reason these teachings were outlawed and excised from Christian dogma back in the fourth century: They meant there was no need for priests or bishops—or hierarchy. By erasing these early interpretations of the founding myths of Judeo-Christian civilization, the fathers of patriarchy (in this case bishops) caused a potentially fatal split between mind and body, Spirit and matter. This split is the essential cornerstone of patriarchy—of the Fathers’ house. I have lived this split alongside my (biological) father and my three husbands. This split is more evident in men (which is what gives it toxic heft, since men currently run things), but it exists to varying degrees in women as well—as my story shows. If our civilization hadn’t been built on devaluing, fearing, and denigrating women, men wouldn’t split head from heart and distance themselves from their emotions, which are supposed to be the domain of women.

I am only at the start of my soul journey, but with my discovery of the early Christian interpretations and having found a community of feminist Christians, reverence is humming back to me.

S

ometimes the open wounds left by regret can become fertile ground for the seeds of restitution. My regrets are that I wasn’t a better parent and that I have had to wait so long to feel like a whole person. People often ask me why have I chosen to work on issues of adolescent pregnancy, sexuality, and parenting. These are the issues that call to me, asking me to try to prevent young people from having to wait as long as I did to respect, honor, and be themselves.

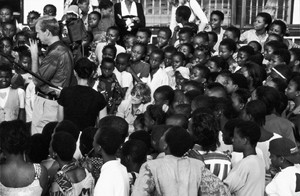

In 2000 I went to Nigeria with staff of the International Women’s Health Coalition to make a documentary about three unique and highly successful programs for girls. Here I am squatting amid a group of schoolgirls in Lagos.

To know what needs to happen to make children resilient and healthy, and to avoid early pregnancy, I can draw on my research, travels, and interviews with parents and youths around the world. But I can also think back on what did or didn’t happen in my own and my children’s early years. The parent—especially the mother (or mother figure), especially in the formative years when the brain isn’t yet hardwired—is the critical factor. And if the mother, for whatever reason (depression, addiction, violence, abuse), can’t show up for her child, another caring, nurturing adult must be found to provide the necessary bond. Fathers, if they are warm and loving, can be crucial to a child’s resilience. The safety of a father’s loving (nonsexual) embrace can help ensure that a daughter won’t seek a man’s love in the wrong places. A son can be inoculated against the toxic effects of patriarchy if his father (or another consistent, loving male) models emotional expressiveness and caring. For girls and boys, being fatherless is less damaging than having a rigid, abusive father.

But whether we are parents, grandparents, aunts, uncles, neighbors, teachers, ministers, or athletic coaches, we all have a responsibility. This means, through our example, showing “perfection” to the door and helping girls respect themselves whether or not they conform to society’s current aesthetic norms; talking to them about feelings, relationships, and sexuality; and, most important, listening to and

hearing

them.

I have talked more about women and girls because . . . well, because I am one of the former and I used to be one of the latter. But over the last number of years I have seen how boys are affected by the same things as girls, only it manifests earlier and differently in boys. I have some very personal reasons for needing to understand boys as well as girls. I have a brother, a son, a grandson, and (more recently) a granddaughter for whom I hope one day there will be an empathetic partner to love. I know that lack of empathy is systemic in the patriarchal culture—one reason my heart goes out to men.

Psychologist Carol Gilligan has three sons and has done extensive research on the development of boys. Her research shows that whereas girls lose relationship with themselves at the start of adolescence (as I did), boys experience this loss roughly between the ages of five and seven, when they start formal schooling. This is when boys can begin to shut down and show signs of emotional stress (depression, learning disorders, speech impediments) and out-of-control behavior. Obviously not all boys experience this. It seems that warm, loving, but structured home and school environments act as vaccines against gender stereotypes.

When little boys begin to go out into the world, they internalize the message of what it takes to be a “real man.” Sometimes it comes through their father, who beats it into them:

Don’t be a sissy.

Or it can be a mother who won’t or can’t respect a child’s real feelings. Sometimes it comes because our culture rips boys from their mothers:

Don’t be a mama’s boy.

Sometimes it’s the “manhood” messages from teachers and the media. It can be a specific trauma that shuts them down, like what happened to Ted at five, when he was sent to boarding school. Think about all the men you know who are oddly divorced from their emotions. This isn’t just a question of “Boys will be boys.” It goes way beyond male/female differences in brain chemistry, and it has had an impact on all of us. Fear of being considered unmanly is so deeply ingrained that I believe a series of U.S. presidents refused to withdraw from Vietnam because they were afraid of being called soft. How many lives have been lost because leaders needed to prove they were “real men”? (And it is usually the poor who are sacrificed on the altar of our leaders’ insecure manhood.)

For their own good, and for the good of every other living thing on the planet, men should join women in leaving the Fathers’ house.

EPILOGUE

“It doesn’t happen all at once,” said the Skin Horse. “You become. It takes a long time. That’s why it doesn’t often happen to people who break easily, or have sharp edges, or who have to be carefully kept. Generally, by the time you are Real, most of your hair has been loved off, and your eyes drop out and you get loose in the joints and very shabby. But these things don’t matter at all, because once you are Real you can’t be ugly, except to people who don’t understand.”

—M

ARGERY

W

ILLIAMS,

The Velveteen Rabbit

I am, gratefully, still a work in progress. I have part of one act to go in which to practice conscious living, be there as fully as I can for my children and grandchildren, contribute in whatever ways I can to healing the planet. If I can do these things, I’ll be able to die gracefully and without regrets. We’ll see.

In three years I will be seventy—which leaves me a little more than twenty years, if I’m lucky. I’ve worked hard to get where I am, and I can tell you with utmost certainty that entering my third act the way I did made all the difference, because it has forced me—every day—to show up, to remember that this is not a rehearsal and that I have promised myself to do what was needed so I wouldn’t have regrets. Things change when you become intentional.

Bit by bit I have learned to love and respect my body. I may have betrayed my body, but my body has never betrayed me. Maybe in our Western culture you have to be a certain age for this to happen: to have lived long enough to love your hips for having enabled you to bear children, your shoulders to bear burdens, your legs to have carried you where you needed to go.

As Viola Fields in

Monster-in-Law,

my first film in fifteen years. It was fun.

(© MMV, NewLine Productions, Inc. All rights reserved. Photo by Melissa Moseley.)

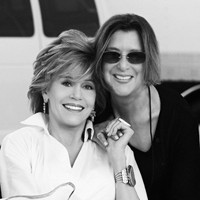

On the set of

Monster-in-Law

with Paula, one of its producers.

(© MMV, NewLine Productions, Inc. All rights reserved. Photo by Melissa Moseley.)

I have known failures. Those I have run from taught me nothing. Those I got to know intimately permitted me quantum leaps forward. The failures are what deliver us to ourselves. You don’t get Real by playing it safe.

In 2004, after fifteen years in “retirement,” I made another film,

Monster-in-Law.

I did it for two reasons: I needed money to create endowments that will ensure the future of the adolescent reproductive health programs and services I helped start in Georgia, as well as professionals to run them. I also recognized that I am a very different woman today than I was fifteen years ago—at once lighter and heavier—and I wanted to see if this would change my acting experience. It did! Unlike fifteen years ago, I felt confident, playful. As of this writing, I haven’t seen the movie, but the process was joyful both in the acting and in the relationships with cast and crew. It didn’t hurt that my beloved friend Paula Weinstein was a producer of the movie and that it was filmed entirely in Los Angeles, where Troy could spend hours on the set watching me work and giving me great acting tips.

Vanessa has long since graduated with honors from Brown University, went on to study English and creative writing at NYU’s graduate school and then to its Tisch School of the Arts to study film. She is a fine documentary filmmaker with two advocacy documentaries under her belt—one,

Fire in Our House,

made with Rory Kennedy (Robert and Ethel’s youngest child), about the effectiveness of needle exchange as a harm-reduction strategy, and

The Quilts of Gee’s Bend.

A granddaughter, Viva, has arrived—as bright and beautiful as a dream. I watch in awe as Vanessa mothers Malcolm and Viva with intention, intelligence, and unconditional love. Vanessa has grown into a woman with strong values, a discerning mind, and a desire to

make it better.

My in-house Jiminy Cricket, she continues to teach me. When I asked her to describe what she does, she said she was “one of the spiders on the web of life, pulling threads between elements—activists, organizations, funding—to create a more cohesive and sustainable whole.” In Atlanta, she is developing a nationally replicable model of an environmental curriculum for preschoolers. She walks her talk.