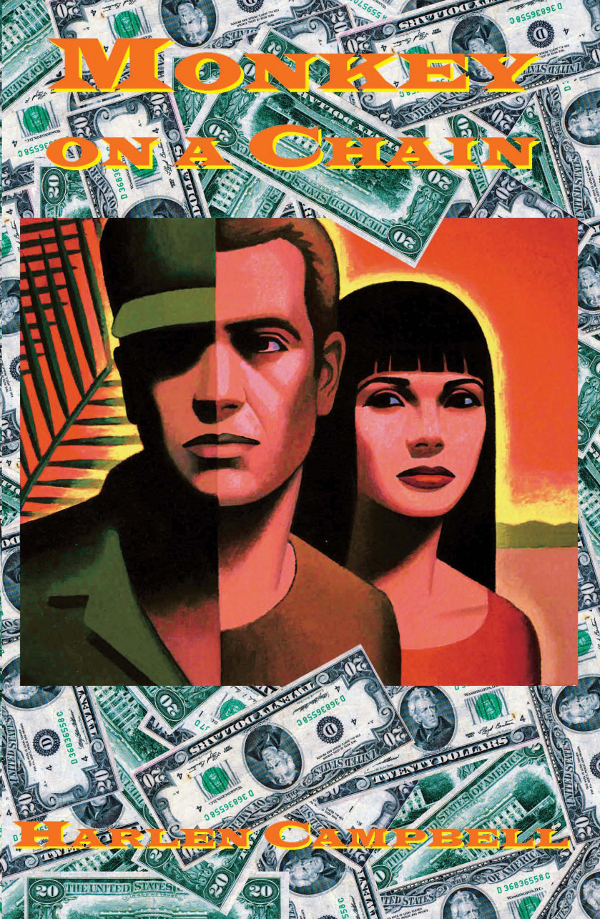

Monkey on a Chain

Authors: Harlen Campbell

Tags: #FICTION / Mystery & Detective / General

Monkey on a Chain

Copyright © 1993 by Harlen Campbell

First Published in 1993 by Doubleday

First Revised Edition 1999 by Poisoned Pen Press

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 99-60115

ISBN: 978-1-89020-812-4 Trade Paperback

ISBN: 978-1-61595-228-1 ePub

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in, or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise) without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Front Cover Design by Alexander J. Perovich

Poisoned Pen Press

6962 E. First Ave., Ste. 103

Scottsdale, AZ 85251

Contents

APRIL

The road to my house twists up the west face of the northern end of the Sandia Mountains. It doubles back on itself in a number of hairpin curves, and it is a hard run. I take it every day, and as I run, occasional breaks in the pine and cedar forest offer a comfortable hundred-mile perspective on the human race.

Even at sea level I hate jogging. At a touch under seven thousand feet, it’s like running in a vacuum. I’d never do it if the twenty-three hours a day when I don’t run weren’t so flat and lifeless without the exercise. It keeps my carcass as lean as can be expected and helps my mirror maintain the polite fiction that I’m still a year or two on the cradle’s side of forty. I hate running, but I do it. Still, I get by with the bare minimum—two and a half miles to the ridge above Placitas and then back again.

The ridge makes a good rest stop. Directly below, the village lies strung along the tail end of the pavement. A pine and juniper forest dies into grassland farther to the west. Beyond that, a golden plain falls away toward the dirty green line that marks the bosque, the cottonwood and scrub cedar forest along the Rio Grande. The dry plain is interrupted only by the thin north-south thread of Interstate 25.

Albuquerque lies to the south, crouched behind a shoulder of the Sandia Mountains. At night, especially when there is a high overcast, the lights of the city provide a waning moon’s illumination. But in the late afternoon, when I do my running, the only hint that five hundred thousand people are playing out their lives twenty miles away is the sunlight glinting from the cars and trucks strung out along the freeway.

From my resting spot, you look down at a steep angle on the white and brown stucco, the adobe, and the weathered wood of the village of Placitas. You look down at a lesser angle to the river, ten miles away. Above the river, the high desert of western New Mexico looms as if you could scratch it with a short stick.

The desert is dry. A wet year brings seven or eight inches of rain and snow. A number of low volcanoes interrupt the mesa toward the southwest. Black on brown. To the northwest lies the dark purple smudge of the Jemez mountains. Seventy miles away and snow-capped most of the year, Mt. Taylor sits on the western horizon like an ancient Navajo god.

There’s a lot to look at if you like things that don’t change from day to day. I stand there, waiting for my lungs to get over their excitement, and I watch nothing happening. Maybe a hawk or an eagle wheeling high overhead, a black speck against the turquoise sky. A woodpecker hammering in the forest. I can take a lot of nothing happening without getting tired of it. I get nervous when things start happening.

That Thursday a car growled somewhere below as it climbed the ridge. I only have five neighbors on my road. I know them all well enough to say howdy, and they know me well enough not to say anything more than howdy back. Only one could be called an acquaintance—Jenny Murphy, who has the place next to mine. Neither she nor any of the others was likely to be traveling at that time of day.

I turned reluctantly from my resting spot and began the jog back. I kept my ears open. The car was a surprise, and I didn’t like it. There had been too many surprises in my past. When it was about a minute behind me, long before I could be seen, I slipped off the road and into the trees and watched it pass.

It was a red ’eighty-seven Jag with California plates and one occupant. Female, dark hair, yellow scarf against the wind, dark glasses. She was driving slowly, as though she didn’t know where she was going or was uncomfortable so far from civilization.

When she was well past, I shrugged and moved back onto the road. She’d kicked up enough dust to make me run with my mouth shut. I set as steady a pace as the terrain permitted. It’s hard to run uphill without slowing down, or downhill without letting gravity encourage you too much, but I had years of practice. I spent the time wondering which of my neighbors had a visitor and checking the dust in their drives.

I have the last house on the county road. When I passed Murphy’s place, I was still following the Jaguar, so I had a visitor. A little prudence was called for.

Half a mile ahead, the driveway cut off to the right and then turned back south. I picked up my pace for a few minutes and then climbed into the forest on the uphill side. At that point, the house was about two hundred yards above me and maybe the same distance north. I slowed to a walk and recovered my breath, then climbed straight up the mountain, well above the house, before turning north. Eight minutes of quiet walking took me to a point from which I could see the front of the house, the driveway, and the graveled parking area. The car sat in the center of the yard, between the garage, below me on the uphill side, and the front of the house.

The girl stood by the front door, looking dejected. She pounded on the door halfheartedly and then stepped back from the house. She walked over to the kitchen window and peered in, then moved to each of the other windows on the front and repeated the process. She tried to walk around the house, but the steepness of the slope and the cactus I’d planted stopped her. She went back to her car and sat in it. After a few minutes, she rested her face against her arms on the steering wheel. Her shoulders shook gently.

I moved silently back along the drive. Once out of sight, I climbed down and began jogging toward the house. I kicked a couple of rocks to make some noise, but the girl apparently wasn’t listening. When I reached the yard, she hadn’t moved. I called out a friendly hello and walked over to the driver’s side of the car.

She was about twenty, Eurasian, pretty. Her black hair fell halfway down her back. Her bangs were cut square above the slope of her eyes. She seemed nervous, so I smiled. “Are you looking for me? I was running.”

She sat up quickly, wiped her eyes, and managed a smile. “Hello. Ahh…you are Mr. Porter?”

She spoke with a faint accent. English wasn’t her first language, but she was comfortable with it.

“What can I do for you?”

She hesitated a moment. “I don’t…do you know…I mean, did you know a James Bow?”

The name threw me. And the past tense. Jimbo. Good old Toker. I kept my voice noncommittal, my face open, friendly, and curious. “Why do you ask?”

“He’s my father. I mean, he was. He’s dead.”

That made no sense. The last time I saw Toker, sixteen years ago, there had been no child. This girl was young, but she wasn’t that young. Maybe half my age. I closed in a little, just in case action was called for. “Sorry to hear it. So?”

She seemed to sag a bit, as if she’d had a lot riding on my response. “Maybe you’re the wrong man. I’m sorry.” She reached for the ignition.

“Maybe not.” I reached through the window and took her keys. “Come in the house. Tell me about it.”

I walked over and unlocked the house, leaving her to follow. My back felt exposed, but what the hell, sometimes you take a chance. If she was armed, she wasn’t carrying anything under that thin silk dress. There was barely room for a bra and panties.

She came in as I was pouring a glass of club soda. Angry and frightened at once, she stopped just inside the door. “You took my keys.”

“You came from L.A.?”

She nodded. “Give me the keys.”

“That’s too long a drive for nothing. Would you like something to drink?”

She licked her lips. “Water. And my keys.”

I handed her a glass and motioned toward the sink, then lobbed her keys onto the dining room table and dug a cigarette from my stash. She watched me, looking surprised.

“You jog and smoke?”

“Nicotine’s good for the soul.”

She savored the word. “My father never spoke of a soul.”

“Maybe he didn’t have one.”

She ignored that. Or maybe she didn’t. “He was a good man. He was good to me. He gave me my car.”

“How did he die?”

“You haven’t said you knew him.”

“I knew him.”

She hesitated, licked her lips. Her lipstick was a deep red. It went well with her coloring. “He was killed. Murdered.” She put a lot of emphasis on the word.

The front door was open. I gave the yard a good once-over, then locked up and led her through the living room and onto the deck that hangs off the back of the house, fifteen feet above the ground. A piece of the county road is visible from there, and you can hear any traffic. The only sound was wind in the pines and an occasional bird. The road was empty.

There is a wrought-iron patio set on the deck. I sat at the table and motioned her to a chair opposite me. She hesitated, but she sat. I considered her carefully. She was good to look at. Her hair was long and straight, brushed until it shone. Her eyes were dark brown, not quite black. The dress was some kind of print, off-white with a pale green leaf pattern. Very snug. Very attractive. But it didn’t look comfortable for a long drive and it wasn’t wrinkled. I decided to clear the air.

“When I saw your father the last time, around ’seventy-four, he didn’t have any kids. Where did you come from?”

“Hong Kong. He was on vacation there when he found me. That was in nineteen eighty-one.”

“You don’t look Chinese.”

“I’m Vietnamese. Half Vietnamese, anyway. My father was an American. I was one of the boat people.” She hesitated a moment. “I was in a refugee camp when Dad found me.”

I had recognized the Vietnamese blood in her face, of course. But this wasn’t making any sense. “You said he found you?”

She nodded. “And brought me home. He took good care of me.” She looked about to cry.

“He was your father? Your real father?”

“Oh, no! My adopted father. My real father was a cowboy. Or that’s what my aunt said.”

A cowboy. How the hell would a Vietnamese aunt recognize a cowboy? And why an aunt? “What did your mother say?”

“That’s what she told my aunt. I don’t remember my mother. She was killed a long time ago. In ’seventy-one.”

A lot of people were. I made a polite noise anyway. “What happened to your aunt?”

“I don’t know. She put me on the boat. She said there wasn’t enough money for her to come with me. A family took care of me, at least until we got into the camp. Then they sort of forgot me. Things were scary in the camp. Everyone was trying to get to America. Maybe Mr. Nguyen thought his family would have a better chance if there were fewer people on the application. But they never got out. Only I did, when Dad found me.”

“And brought you to America.”

She nodded. “And put me in school. Then helped me get into UCLA.”

“And now he’s dead.”

She lowered her head and blinked.

“Tell me about it.”

She swallowed. “I was in class when the police came. Mrs. Stillwell told them where I was. They told me he was dead and then they took me to her. She lives right next door. She heard the explosion and ran over and found him and called the cops.” She took a deep breath. “They wouldn’t let me see him. I guess he was messed up pretty bad. They said it was a clayman bomb. In his office.”

“A Claymore.”

“What?” The interruption confused her.

“Not a clayman. A Claymore. It’s an explosive device a little bigger than a paperback book,” I told her. I didn’t add that they can make a hell of a mess if they’re used right. She knew that. After a moment, I asked, “Who did it?”

“They don’t know.”

“Do they know why?”

She shook her head. “It wasn’t money. Nothing was taken. At least then. And he didn’t have any enemies. He was just a businessman. He had a foreign car dealership in Westwood. I don’t know why anyone would do this.”

Of course he’d had enemies. We all do. I hoped that he had made some recently. And the dealership. He’d put his share to good use. It also explained the Jaguar the girl was driving. “When did this happen?”

“Tuesday. Two days ago.”

I whistled. I’d thought we were talking about something older, something she could have a little perspective on.

“Why are you here?”

“Mrs. Stillwell asked me to stay with her that night. The police let me in the house to get some things. I guess I was kind of numb. I didn’t notice much. The door to the master bedroom was closed and I could hear some men talking in there, but everything else looked normal. Anyway, I took my toothbrush and went with Mrs. Stillwell. But later, way after midnight, when I was trying to sleep, I remembered…something. I went back to get it, but there was this tape on the door that said it was a crime scene, and I was afraid to break the tape. I got a flashlight from my car. I was going to climb in my window.”

“You what?”

She blushed and looked away from me. “I used to do that sometimes, when I was in high school. When I was grounded.”

I wondered if Toker had known. “Okay. So you broke in. Then what? Why did you come here?”

“But I didn’t! I was going to, but when I looked in the window, everything was a mess. It looked like the house had been searched or something. Things were upside-down. The drawers were emptied on the floor. I looked in all the windows. It was the same everywhere.”

She took a few deep breaths. “His office was there, in a little sitting room off his bedroom. I even looked in there…where it happened…and it was torn up too. There was stuff thrown on the blood and on the outline of his…of Dad’s…”

She was right on the edge. I looked out over the valley while she composed herself. It took a while, but not as long as I expected. This wasn’t the first bad thing that had happened in her life.

“…anyway, I thought I might be in danger. Because it wasn’t the police, you see. When I was there, they were being pretty neat. So I thought somebody else had been there, in my house, and that scared me. I got my purse from Mrs. Stillwell’s and then I just got in my car and started driving. At first, I didn’t know where to go. But a couple of weeks ago, Dad told me to come to you if I ever needed help. He was very serious about it. He even wrote down your name and address and put it in my purse. He told me to say something to you.”

That got my attention. My eyes jerked to her face. “What?”

She looked straight into my eyes and said, “You owe me.”

“That’s all?”