Miracle at Augusta (13 page)

Read Miracle at Augusta Online

Authors: James Patterson

LESS THAN THREE WEEKS

ago, sitting in my den with Louie, I watched Sam Snead walk onto the first tee and hit the ceremonial first shot of the '98 Masters. Now I'm watching Jerzy Solarski, a seventeen-year-old from Bucharest, who three months ago knocked on my door with a shovel, tee it up from the same spot. Almost as unlikely, I've now spent two hours on a course where I've fantasized playing for forty years, haven't taken a single swing, and don't seem to mind.

With Hootie and company sipping their second or third cocktails, Jerzy and I have Prosper Berckmans's former nursery entirely to ourselves. You could argue that the experience is more rarefied than actually playing the Masters, where you're obliged to share it with the likes of Tiger and Phil, a hundred other pros, and tens of thousands of fans, I mean

patrons.

Aside from those snippets of an old-timer stooping over on the first tee on Thursday nights on ESPN, the front side is untelevised, and that makes playing Tea Olive, Pink Dogwood, Flowering Peach, and Flowering Crab Apple a lot different than playing Camellia, White Dogwood, and Golden Bell. From our shared reading, Jerzy and I know the approximate layouts, but we haven't witnessed golf history on every hole. That takes the edge off considerably, and as the sun begins its swift descent, Jerzy pars two of them and the par/bogey train keeps chugging through the Georgia pines.

As we walk off 5, Magnolia, the sun dips beneath the trees, and now the birds stop chirping. Engulfed in quiet, it's harder to ignore the question I've been dodging all day, if not all week, which, of course, is “Why?” Why are we doing this? What message am I trying to convey? What, if anything, am I hoping to instill in an impressionable young mind beyond a healthy disrespect for private property and a love for destination trespassing?

Well, here's my answer. To have some fun in this life and avoid swallowing a mouthful of shit per day takes more than luck, and this is a lesson, however ill-conceived, in audacity. If the last year or so has taught me anything, it's that every once in a while you need to take a deep breath, do your best impersonation of a badass, and see where it goes. If nothing else, you might make some new friends as interesting as Earl, Stump, and Jerzy, and what's more precious than that?

On the famous back nine, we felt like a couple of tourists gawking at golf's Eiffel Tower. Finally, we can just play. Hit it. Find it. And hit it again. Do that, good things tend to happen, even to mediocre golfers. Over the next three holes, Jerzy cards two more pars, and when he slides in a six-footer on 8 for the second one, the laid-back quality of our afternoon evaporates. Suddenly, I'm as nervous as I was walking beside Earl up the 18th fairway at Shoal Creek on Sunday.

“YOU KNOW WHERE WE

are right now?” asks Jerzy.

“Number nine,” I say, “Carolina Cherry. Golf course called Augusta National.”

“In addition to that?”

“Eight over,” I concede.

“Correct. So I need to birdie one of the next two.”

“Yup.”

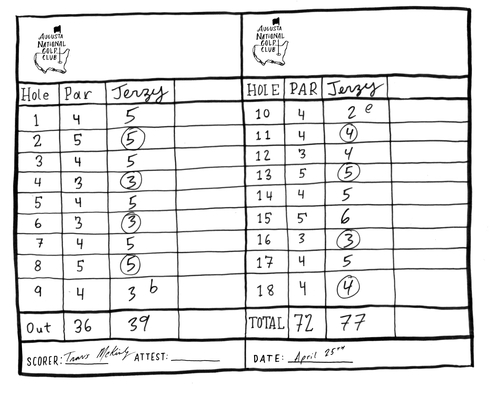

If my share of the dialogue seems flat, it's intentional. I appreciate the weight of the moment, at least as much as Jerzy, but I'm doing my best to pretend otherwise. After sixteen holes, Jerzy has eight pars and eight bogeys. Since Augusta National is a par 72, that means he's sitting on 80, and if he can play the next two holes in 1-under-par, he'll shoot 79.

For every hacker who's ever teed it up in vain, breaking 80 is the Promised Land, and getting there for the first time is like meeting Saint Peter at the pearly gate. In terms of personal significance, it trumps playing Augusta National, Pebble Beach, and St. Andrews combined. It isn't even close. Let's say that on the same day that you eked out an 83 at Augusta National, you drove to a muni on the wrong side of town and shot 79, “no gimmes, no mulligans, no bullshit,” to break 80 for the first time. Which round at which course do you think you'll be replaying in your mind all night? I'll give you a clue. It's not the one with the azaleas.

On the other hand, if you're going to break 80 for the first time, Augusta National is a highly auspicious place to do it. In order of magnitude, it would be like losing your virginity to Marilyn Monroe. And having a signed document, suitable for framing, to verify it. People have gone on to become president for a lot less.

Unfortunately, Jerzy's chances of doing one are about as good as the other, and Marilyn, bless her generous soul, has been dead thirty-six years. The problem is the difficulty of our remaining two holes. The 9th, with its signature three-tier green, is one of the hardest on the front nine, and the 10th, a 495-yard par 4, is the hardest hole on the course. The last two holes are so long and tough that playing them even would constitute a minor miracle, but as I guess you know, the name of this book is not

The Minor Miracle at Augusta.

“So how am I going to get this done?” asks Jerzy.

“Birdieing nine would be a good start.”

JERZY AND I STAND

on the 9th tee and squint at what's left of the fairway. There's so little light, the only way to get an idea what we're facing is to pull out the yardage book. With Jerzy squinting over my shoulder at the diagram, I lay out the challenge. Since we both know he needs birdie, I don't sugarcoat it.

“Carolina Cherry is a dogleg left. Downhill off the tee, uphill to the green. It's all about the tee shot. If you can get it to the bottom of the hill, where you can hit a short iron or even a wedge on your second, you've got a much better chance for birdie. To do that, you need to get all of it, and it's got to be straight, because there are trees on both sides.”

Jerzy's tee shotâa low hard topâis on me. Tell a seventeen-year-old, or even a nearly fifty-two-year-old, he needs a big drive, he's going to overswing every time, and despite the lousy light, I know it's nowhere near the bottom of the hill. As we soon discover, it hasn't even rolled off the top plateau, and when I step off the distance to the nearest sprinkler head and do the math, I get 221 to the center of the green.

There's just enough light to make out the flag on the left side, and by referring to the yardage book, I determine that it's cut in the second of the three tiers. When I also see that the green tilts sharply from back to front and, to a lesser degree, from left to right, I can't resist a dark smile. The only shot with a chance in hell to stay on that second tier, where he would have a realistic putt at birdie, is the one I practiced all winter at Big Oaks. And he's got to hit it, not me.

“You're in luck,” I say. “This calls for a high draw, and I'm something of an expert on this shot. We could spend a month on it, but here's the fifteen-second tutorial: move the ball back closer to your right foot, close your stance, and think about hitting the inside of the ball.”

I feel like a quarterback sketching a play in the dirt on the last drive of the Super Bowl, but I'm not Bart Starr and Jerzy's not Paul Hornung. Or maybe he is, because in his first attempt, with 79 on the line, he hits it purer than I did all winter with nothing at stake, and before the ball disappears from sight, we can see it bend gently toward the flag.

“Congratulations, Jerzy. According to your new friend Earl Fielder, you just hit the suavest shot in golf.”

“Who am I to contradict Earl?” says Jerzy.

Now all that's left is the minor technicality of that pesky twenty-two-footer. Jerzy steps up to it as if it holds all the peril of a tap-in and rolls it dead center. Let's see what he's like in thirty years after he's missed a mile of five-footers.

“JERZY, THAT WAS SWEET.

Now all you got left is the hard partâmaking a four on ten.”

Somewhere between the 9th green and the 10th tee, the last bit of light drains from the sky. If this were a tournament, they'd have sounded the horn thirty minutes ago. At least we're on the back nine again, and along with Owl's trusty yardage book, we have the benefit of having seen this hole in Central Time on CBS.

“Another downhill dogleg left,” says Jerzy, squinting at the diagram. “Looks like nine.”

“Particularly in the dark,” I say. “This one is forty yards longer, but there's a speed slot on the left side of the fairway. If you can drop it in there, it plays about the same. Take a three-wood, put an easy swing on it, and let the slope and gravity do the rest.”

As a preamble, it's a helluva lot better than what I came up with on 9. Jerzy strikes it solid, gets the sought-after roll, and when we find it just off the left side of the fairway, 185 yards from the center of the green, this absurd pipe dream still seems possible. From here, the green is harder to see than the flag, but by working off the sand on the right and the yardage book, I place the flag back and left.

“You've got one ninety-three to the pin,” I say. “It's cooler now, so it's going to play all that. Aim for the right side of the green and don't worry about the bunker. It's much better than being left.”

I hand him the 4-iron, and Jerzy delivers his third pure swing in a row, like he's just getting warmed up. In fact, it's too good, or maybe he catches a flier, or more likely I gave him the wrong club, because he airmails the green. After it soars over the trap, it disappears from view, and as we tilt forward and strain our ears in that direction, we hear it hit a branch and then another and maybe even a third.

Just like Shoal Creek all over again, I think as the pines play pinball with Jerzy's 79. Last hole. Last swing. All we need is par, and I pull the wrong stick. Funny thing about golf acousticsâsometimes a ball hitting a tree sounds exactly like a ball splashing into a pond.

WITH THE RESILIENCE OF

youth, Jerzy bounds after it.

“Jerzy, wait up. I got to make you hit a provisional. In this light, we might never find that ball.”

Even if we don't, and Jerzy limps home with a triple, he still shoots 82, and the last thing I want to do when this is over is hand him a scorecard with a big fat asterisk attached. Whatever he shoots today is going to be legit. No gimmes. No mulligans. No bullshit.

I hand him the 5, and he goes through the same routine he did with the 4âa practice swing, a waggle, and go. Again he hits it well, and when we get closer, we see that it's rolled onto the front edge. Then we head to the spot beyond the right trap where his first ball disappeared.

In the trees, it's three shades darker, and a glance at my watch shows we're coming up on our appointed rendezvous with Earl and Stump. By now it's a cool Georgia nightâall pretense of a late afternoon or early evening is goneâand we spend the next few minutes weaving through the pine straw trying to will a Titleist into view. When that doesn't happen in five minutes, I call off the search and we return to the green.

“All that means,” I say, “is that you're going to have to make one last putt. The goal was to get you on the green with a putt for par, and we've done that. Whether his name is Ben Crenshaw or Dave Stockton, there is no one I'd rather see putt this ball than you.”

I don't know what makes the putt harderâthe distance or the darkness. Between the ball and the flag are over a hundred feet of barely visible green, and a big break from right to left. I wish I could be more specific, but in this light, I can't. The only thing in our favor is that it's uphill.

I know that in the course of this tale, I've pushed your credulity to the limit. If I tell you Jerzy drains a 110-foot putt with about 20 feet of break in total darkness on the hardest hole at Augusta National to break 80 for the first time, will that be a bridge too far? In any case, all I can do is tell you what happened.

After we've learned all that we can by studying an invisible green, I send Jerzy down to his ball with his magic putter and I head to the hole to tend the flag. At the bottom of the green, Jerzy is a dark shape, and behind him at the top of the hill, the light in the Crow's Nest looks like a low moon. “Don't be afraid to hit it. The one thing you can't do is leave it short.”

On opposite ends of the green, Jerzy takes his practice strokes and I reach for the pin. I've already made one gaffe on this hole. I don't want to compound it by getting the flag stuck and then yanking so hard that the entire cup comes out with it. To ensure that the flag will slide out smoothly, I twist it back and forth, and something rattles at my feet. When I look down, I see a white Titleist with a blue

J

and

S

on each side of the 3.

“Don't putt it, Jerzy,” I manage to shout in time. “Pick it up. Your first ball is in the hole. You didn't just break eighty. You broke seventy-eight.”

Here's the final scorecard after I pencil in his 2 on Camellia. No matter how many times you add it up, it comes to 77.