Miracle at Augusta (10 page)

Read Miracle at Augusta Online

Authors: James Patterson

THE FOLLOWING TUESDAY, I'M

back in the New Trier parking lot waiting on Jerzy and the bell, and once again, I'm not alone. Till now, I'd never appreciated the commitment, discipline, and punctuality required to be a top-notch high school bully. Less motivated sociopaths-in-training would be in the library reading a muscle mag or carving sinister symbols into a desk. Instead, they're out here freezing their asses off behind the maintenance shed and choreographing their next ambush.

My rivals are conscientious, but I have the element of surprise. This morning I persuaded Sarah to swap cars, so that while I keep an eye on the boys in black, they take no notice of the green Jeep or the man behind the wheel, his face buried in the afternoon paper.

From my reading, I learn that the Trevian hoopsters dropped their ninth straight last night to archrival West Hill. The photograph shows West Hill's Dave Bond scoring over a New Trier player with distinctive straight bangs named Brune Pickering, and according to the box score, Pickering led the losers with eleven points and seven assists. Is that all it takes to become a total shit?âbe the best player on an awful basketball team, and be saddled at birth with the name Brune? Whatever.

When the bell goes off, I close the paper and scan the exits. This afternoon, Jerzy makes his retreat from the study hall. While the Parkas move to intercept him at the end of the walkway, I roll up from the other side of the lot, moving slowly so as not to be noticed.

As I inch along, I study Jerzy's face and body language and am encouraged by what I don't see. There are no fresh wounds on his face or neck, and his gait doesn't favor one side or the other. Wishful thinking, maybe, but I also detect a new bounce in his step and a hint of defiance.

Unaware that anyone else is eyeing their prey, the boys take their time. That allows me to slip in front of them just before Jerzy reaches the end of the walkway. When Pickering spots me, I've already reached across and opened the front door and called out in an urgent whisper, “Hey, Jerzy, it's me. Get in.”

Jerzy is so close the front door nearly hits him, yet nothing in his expression indicates he sees me. The blank mask he adopts for his tormentors is now aimed at me. Instead of climbing into the safety of the Jeep and heading to Big Oaks, he walks directly past the car into a whirlwind of flying fists.

THREE DAYS LATER, I'M

back at New Trier again. This time I park and walk around to the main entrance, where I inform the guard I have an appointment with the assistant dean of students, Reece Halsey. On the way to Halsey's office, I must make a wrong turn, because instead of entering the administrative wing, I find myself in a wide hallway lined with classrooms. The classrooms are empty and so is the corridor, but the tin lockers and low water fountains drum up a parade of ancient memories, mostly lousy.

When the corridor ends, I turn in the direction of the noise, which grows more urgent with each step till I push through a pair of doors into a vast rotunda. The multicolored flags of every nation, presumably including Rumania, hang from the high ceiling, and to my left is a stack of faded green plastic trays. I grab a tray and a plate and watch a woman wearing a hairnet ladle something brown onto something white. Then I slide the tray over the rails, fill a paper cup with something pink, and face the din.

The cafeteria must hold a thousand students. Nine hundred and ninety-nine of them crowd around a hundred tables, and one, his jug head tilting toward the straw in a carton of milk, sits alone, surrounded by empty chairs.

“What are you doing here?” he asks.

“I hear the chef does an amazing beef stew.”

“Yeah,” says Jerzy. “He opens the can.”

As I take my first bite, a wet napkin lands with a splat at the center of our table, setting off a round of laughter.

“There's something I want to tell you, which I haven't shared with anyone in thirty-five years. Not my wife, my kids, or my best friend. Not even Louie.”

“Louie?”

“My dog. I believe you two have met.”

Half a muffin hits the table, followed by several packets of salt and pepper. I open one of each, sprinkle them on the stew, and take another bite.

“In eighth grade, the same shit happened to me. At that point, I was as tall as I am now, absurdly skinny, braces, glasses, an all-round winning look. This kid named Rudy Laplante, who happened to be the scion of a huge trucking company, decided he was going to make my life miserable, and for several months did a thorough job. At one point, my mother found out what was happening. You know what she said I should do?”

“No.”

“I guess you wouldn't, since I haven't told you yet. Take a chair and smash it over his head.”

“Did you?”

“What do you think? But I've always been grateful for the suggestion.”

“Just as well. You could have fractured his skull. How would your mother have felt then?”

“You know, I've wondered about that. One possibility is that she knew I wasn't capable of it. The other is that she didn't give a shit. Figured that was Rudy's problem. I prefer that one.”

“You saying I should smash a chair over Pickering's head?”

“In your case, that probably wouldn't be a good idea, although I'd love to watch, if you did. In fact, I'd pay to watch.”

The aerial assault picks up and the incoming turns healthierâgrapes, pineapple cubes, an apple core, a bananaâand Jerzy and I ignore it all, having reached an unspoken agreement not to give the assholes the satisfaction. More miraculous than the manna from heaven is the arrival at our table of another student. She is small and thin and wears a black Smashing Pumpkins T-shirt over a black vintage dress, with black nail polish and black lipstick. In addition to being monochromatic and brave, she's pretty.

“Welcome to Pariahville,” says Jerzy. “Population three. I hope you brought an umbrella.”

“You're funny,” says the girl.

“I think you mean funny-looking.”

“No, I mean

funny,

” she says with a touch of impatience. “As in witty. And I like your blazer. Very Angus in AC/DC. All you need is the shorts.”

You're right, that's all he needs.

But I appreciate the sentiment. To me she looks like a black angel.

“So, Jerzy, we good?”

“Yeah.”

“See you next week, then,” I say, and wielding my tray like a shield, I head for the exit.

THE FOLLOWING WEEK WHEN

we return to Big Oaks, Jerzy grabs the 7-iron and swings without discomfort. Pain-free, his move is as long and loose as Sam Snead's.

“Pickering's appendix burst,” explains Jerzy. “He's been out all week and could be out for a month.” I would rather have heard he's on life support, but I'll take it.

“How about that wonderful girl? Any more interaction with her?”

“Which girl?”

“Don't give me that âwhich girl.' The one who joined you at lunch.”

“Lyla,” says Jerzy. “Of course not. That was a once-in-a-lifetime event, like Halley's Comet.”

“She likes you.”

“That's a physical impossibility. As far as I know, she's not blind.”

“She's not. She commented on your attire. Favorably. In any case, between Pickering's appendix and Lyla's Comet, I'd say things are looking up. I propose we show our gratitude, up the ante, and go to work.”

That afternoon, we spend almost four hours in the stall. Jerzy makes so much progress, we decide to come back the next afternoon and Thursday, and in our third session, Jerzy has a breakthrough that most golfers never do. He learns how to “save it for the bottom,” as in connect his considerable size and heft to the bottom of his swing where the club meets the ball, the only part that matters. It sounds like a shotgun and turns every head on the range.

“That was stupid long,” I say as his 3-wood bounces off that old Srixon banner. “At least thirty yards longer than I hit that club.”

“You're not exactly a spring chicken, Travis.”

“True. I'm a September chicken.”

Over the next couple of days, he tattoos the old banner so many times that it finally gives up the ghost, detaches from the wire curtain, and flutters to the ground. “I can't tell you how long I've been waiting to see that,” I say. “Like Berliners when the wall came down.”

The bigger revelation comes a week later, when I hand him my old bull's-eye putter and walk him to the green rectangle about the size of three parking spaces which they have the temerity to call a putting green. I don't know if it's up there with Harvey Penick and Ben Crenshaw at Austin Country Club, but I'll never forget the first time I see Jerzy roll it on the Big Oaks cement.

Putting is two thingsâaim and feel. Aim is the easy part. With practice, almost any asshole can do it. Feel, sensing how hard to strike a putt to make it roll the desired distance, is more elusive and nearly impossible to teach. After giving him a chance to get acclimated to the speed, approximately like putting on a bowling alley, I drop a tee ten feet away and ask him to stop the ball beside it. When that proves a minor challenge, I drop four more at three-foot intervals, then place five balls at his feet and ask him to roll each one to the next farther tee. When he's done, I realize I've underestimated his potential.

“Jerzy, I got some good news. You can hit it long and you can putt. If you can do both, you can play. As in really play.”

BY NOW, IT'S THE

third week of March, and that weekend a lovely thing happens. It gets warmer. That Saturday and Sunday it soars into the high thirties, causing the snow to lose a bit of its grip and giving the ground a chance to thaw. Monday morning, it's back into the twenties again, but by then it's too late. When I pick up Jerzy at school that afternoon, Louie sits beside me on the front seat.

“I don't think they allow dogs in Big Oaks,” says Jerzy.

“They don't allow dogs where we're going, either, but since no one will be there, it's not going to be a problem.”

Instead of the haul up 38, we make the shorter trip to Creekview Country Club, where, with half the course still under snow, the lot is empty.

“It's time to go golfing,” I say as we hop out of the car. “I got one of my old bags and put together a set for you. I've got literally hundreds of clubs in my basement. It's really no big deal.”

“It is to me, Travis. Thanks.”

“My pleasure,” I say, then reach into the trunk for the Big Oaks caps I bought that morning. “This is so we don't forget where we came from.”

“Representing,” says Jerzy as we doff our new caps.

With Louie trotting behind us, we make the short walk to the practice range, where we hit and shag a dozen balls apiece. Then we roll a few on the muddy practice green.

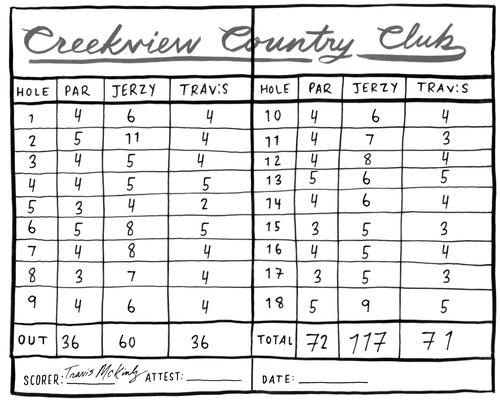

“This is your first round of golf,” I say. “That's a big deal, so we're going to play for real. Because of the conditions, it's got to be lift, clean, and place, which means we can pull the ball out of the muck, wipe it off, and place it in a playable spot, but we're going to write down every stroke, and when we're done, we're going to add them all up. Golf is a number. That's all it is, and the only way to see if we're on the right track is to keep score. So as my grandfather used to say, âNo gimmes, no mulligans, no bullshit, let's play golf.'”

Despite the twenty-eight degrees, the three of us enjoy a lovely afternoon, and it occurs to me that when it comes to golf, Twain got it exactly wrong. Rather than

a good walk spoiled,

it's a crappy walk made bearable. Golf takes what would otherwise be a tedious eight-mile hump, marred with far too much self-reflection, and makes it interesting. Just because you don't know the name of every tree and bird, and couldn't care less, doesn't mean you don't appreciate being outside, feeling the breeze on your skin and the ground underfoot. And just because you have a little hand-eye coordination, that doesn't make you a lightweight.

Jerzy, it turns out, has more than his share of hand-eye coordination, and although he hits four bad shots for every good one, he takes pleasure in them all, just like that first afternoon at Big Oaks. Pop would have appreciated that, the same with Jerzy's brisk pace of play, which allows us to get around in two hours and finish before the sun disappears. On 18, Jerzy rolls in a twelve-footer for 117, and we tilt our caps and shake hands.

“Thanks, Travis. What a wonderful day. I'm only sorry I didn't get a chance to meet your grandfather.”

“You met him eighteen times. His ashes were sprinkled on every green.”

We get in two more rounds that week and, with Pickering still recuperating, three more the following. Along the way, Jerzy's scores dip steadilyâ116, 109, 97, 88, 83, and when I pick him up the following Monday, I feel like he's got a legitimate chance to break 80, particularly with the breeze down and the temperature hovering around forty. Unfortunately, his right eye is swollen shut.

“I take it Pickering has made a full recovery.”

“Correct.”

“What are you doing Sunday?”

“Watching the Masters, of course.”

“Then come over and watch it with us.”

Â

In case you're interested, here's the scorecard from Jerzy's first round of golf:

Â