Millions Like Us (52 page)

Authors: Virginia Nicholson

None of us knew how much longer we were going to be in the Air Force, or when we were going to get out. The war basically stopped. There was no more wartime flying. And so air crew were redundant and they didn’t know what to do with them. So they sent them to the Motor Transport section and told them to go and be drivers – and of course that was our job. So there was quite a bit of resentment of these air crew. And a lot of people were at the end of their tether and were quick to flare up, and there were lots of frictions.

Everybody was given a demobilisation number. When your number came up, you went to the Demob Centre and were sent home.

Flo Mahony’s friend

Joan Tagg, a wireless operator, had joined the service later than she had, so didn’t expect to be released as early. But the great pride she had taken in this important and highly graded job suffered a mortifying blow when, in the summer of 1945, it was stopped overnight, and she was posted to Gloucester to do number-crunching in the Records Office:

The men were coming back, and the men automatically took over our jobs. We weren’t wanted … And this was the worst possible posting they could give me because it was clerical. Also, when they posted me as a clerk they wanted me to remuster, which meant going back two grades. I had loved being a wireless op, and I was absolutely livid.

Men and women alike chafed at the tin-pot bureaucracy and officiousness that now prevailed. ‘The day war ended they started the spit-and-polish,’ says Joan. Flo agrees: ‘The Air Force was known for being relaxed compared to the army. But now there were so many people sitting about with not enough to do, and suddenly, you had to go on church parade, you had to do this, you had to do that. You had to be properly dressed. And they started making us do drill all over again.’ There was work, but it seemed to have no purpose. Idle servicewomen – and men – were encouraged to attend EVT (Educational and Vocational Training) classes to prepare them for civilian life. A future as a shorthand typist or counter clerk beckoned.

Still in Italy

with the FANYs, Margaret Herbertson took up the offer of a job as ‘FANY Education Officer’. She too remembered the early days of peace as having an anti-climactic quality. The flow of signals had completely dried up, leaving coders and intelligence officers like her with nothing to do. ‘We all felt quite dazed. The war, for many of us, had lasted for over a quarter of our lives. I spent a day tearing up papers.’ The War Room, with its atmosphere of feverish urgency, its charts and diagrams, had been dismantled. As far as getting home was

concerned, priority went to servicemen who had spent far longer abroad than the girls. Some of the FANYs immediately volunteered for the Far East. Others just applied for leave and went on sightseeing tours round Tuscany.

Ironically for her new appointment, Margaret had herself opted out of education when she first decided to join the war effort back in 1939. But, untaught though she was, her superiors put her in charge of batches of FANYs who came seeking instruction in English Literature, Current Affairs, Needlework, Art History, Italian and so on. Hastily, she assembled a rag-bag of tutors, including nuns, librarians and miscellaneous semi-qualified colleagues, and together with them devised a reasonable programme, which included educational outings. These last were fraught with peril. Every bridge in central Italy had been blown up by the retreating German army, and an improving day out to admire Quattrocento frescoes in the hilltop town of San Gimignano involved a spine-chilling detour up a zig-zagging 1 in 10 gradient. The road was barely wide enough for the three-ton truck, and the girls closed their eyes, clinging to the sides of the vehicle and praying. Undaunted, in June Margaret organised a cultural trip to Venice: getting there took fourteen hours across mountain passes, negotiating pontoons and carrying their own tinned provisions – but no tin-opener.

By July arrangements were under way to send the FANYs back to England. Margaret had the job of processing despatch of their luggage, and ticking innumerable boxes relating to the hand-in of their uniforms: 952 small sleeve buttons, 310 tunic buttons, et cetera, et cetera. On 11 August 1945 she and her group of eleven girls piled their cases on to two army trucks and said goodbye to Siena. ‘[It] has continued to tug at my heart.’

Then followed an experience which would be shared by returning personnel worldwide. Transit camps had all of the discomforts of barracks and billets, but none of their well-worn cosiness. Add to that the daily frustration of petty-fogging army bureaucracy and the intense heat of a Neapolitan August, and it was unsurprising that morale became low after three weeks not knowing when shipment would happen. Several of the FANYs became ill. At last, on 3 September, they embarked on the

Franconia

, ten of them sharing an airless cabin. On board were thousands of troops, and an apprehensive huddle of young women – Italians, Yugoslavs and Greeks – who

were being sent to England: a shipment of foreign brides. ‘The weather, at first hot and sunny, grew grey and overcast as we sailed north west towards the Irish Sea.’

QA Lorna Bradey

arrived home in Bedford to an ecstatic welcome from her family. But after the brilliant colours of Genoa and Naples, everything looked shabby and diminished. And just as she had feared, things at home were very different. Lorna and her sister had always shared an unstrained intimacy; but when she opened her trunk, she found to her fury that her sister had ‘borrowed’ all her clothes. It took a while to appreciate that the family had been struggling for years to scrape by. Her mother – always selfless, never petty – said nothing as her hungry daughter polished off the week’s butter ration at one sitting. But the first question on everyone’s lips was, did she have any coupons to spare? ‘No, was the firm answer.’ She would have to go out, join a queue and get some. After Italy, home was all a dreadful anti-climax.

I tried to get into the pattern of life – but I was lost. We had nothing personal to say to one another. If I talked about my experiences they were politely interested. They just did not understand.

Tomorrow’s Clear Blue Skies

For many, the weeks following the celebrations felt haphazard, disorienting. There was peace – but it was not peaceful. The final thrust of the Allied victory in Europe, and Germany’s last ghastly spasms, had subsided. But the after-shocks reverberated: there were journeys, telegrams, arrivals, departures, greetings, upheavals, reunions. There were marriages, and divorces. There was grief, mourning and fear about the future. So many people’s lives were still precarious, unsettled, subject to the agitating inconsistencies of authorities and politicians. Children had to be returned to their parents, sons to their mothers, husbands to their wives. In the longer term houses needed to be built and jobs found. In Europe the infrastructure was collapsing; populations were starving. And as the war in the Far East still dragged on, there was another great exodus of soldiers on their way to the battlefields of Burma, Malaya and Java.

It was hard, in those days, to feel any faith in the promise held out by Vera Lynn’s heartfelt rendition of the Irving Berlin lyric, ‘It’s a Lovely Day Tomorrow … ’. On 23 May, a fortnight after VE-day, Churchill’s Coalition government was disbanded. A General Election was called for 5 July.

What kind of world did women want? On the whole, nothing too radical. There is little evidence that Britain’s women were emerging from the Second World War with plans for a feminist revolution or a Utopia. Working on Sheffield’s city trams as a ‘clippie’ during the war,

Zelma Katin had become

known as the ‘Red Conductress’; throughout, she had made her voice heard at meetings of the Transport Workers’ Union. She made common cause with the workers, moved to solidarity with them by the injustices she saw regarding pay and hours, and displaying an admirable stamina on committees. When hostilities ended she felt grateful for all the insights her contact with the proletariat had given her and looked ahead to a brave new world. But more than a new world, Zelma just wanted a rest:

I will confess that I am thinking not only of a future for humanity but a future for myself. I want to lie in bed until eight o’clock, to eat a meal slowly, to sweep the floors when they are dirty, to sit in front of the fire, to walk on the hills, to go shopping of an afternoon, to gossip at odd minutes …

‘And is this – THIS – your brave new world?’ you ask.

Yes; just at this moment, when I’m hurrying to catch my bus for the evening shift, it is.

There were exceptions.

Naomi Mitchison’s socialism

had remained intact throughout the war: ‘I doubt if anything short of revolution is going to give the country folk the kick in the pants which they definitely want, or rather need.’

Vera Brittain had spent

a lifetime espousing both feminism and pacifism, which to her were two sides of the same coin. She had not hesitated to attack the leadership of Winston Churchill, continued to press for women’s equal participation in public life and found in her husband’s candidacy for the Labour Party a further cause to back. Left-wing women like this had plenty to vote for, a world to be conquered.

After the First World War women’s history had turned a corner. In 1918 the vote had been granted to property-owning women over the

age of thirty, followed by the full vote in 1928. But there was no comparable prize for women in 1945. After six long years of home-front survival Nella Last, and thousands more like her, were deeply tired.

On VE-day Nella

felt ‘like death warmed up’. It was a sensation that could only be alleviated by restorative contact with nature. Coniston Lake worked its usual magic:

It was a heavy, sultry day, but odd shafts of sunlight made long spears of sparkling silver on the ruffled water, and the scent of the leafing trees, of damp earth and moss, lay over all like a blessing.

Nella decided to vote Conservative. ‘I don’t like co-ops and combines, I hate controls and if … they

are

necessary from the economic point of view, I don’t want them so obvious and throat-cramming.’ For so many women like Nella, her home was her area of control. That May, the Lasts finally got workmen in to refurbish their bomb-damaged house. Carpets were relaid, electrical fittings rewired, and the pelmets were replaced over the windows:

By 4.30, all was straight, and the air-raid damage, the shelter and the blackout curtains over my lovely big windows seemed a nightmare that had passed and left no trace.

In 1945, the average British housewife cared less about broader issues and a great deal more about the roof over her head, about queues and food shortages. These had got so bad by the end of the war that one of them, fifty-year-old Irene Lovelock, decided to found the British Housewives’ League.

In June 1945 something inside Mrs Lovelock snapped.

The wife of a Surrey vicar,

she returned home in a state of rage after spending a long morning queuing for food in the pouring rain; her fellow queuers included grandmothers and women with small babies in prams. She marched into the house and, though she had no experience of leading public meetings, told her husband she wanted to borrow the parish hall. There she took the platform and soon found herself waxing eloquent on the subject of queues and malevolent shopkeepers. Realising that she had tapped into a profound well of resentment, she then wrote to the local paper and got a huge response. The movement snowballed, and in July Mrs Lovelock became chairman of the BHL Committee, heading up a campaign to improve the lot of

housewives and their families. In the early days there were only a few hundred members, whose principal targets were the manipulative shopkeepers who expected women to wait, often for an hour, until they were ready to open the shop. Provisions were then issued to the front of the line until – often within half an hour of opening – they cried out ‘No more’ and banged down the shutters. This happened all too often – particularly, it seemed, in the case of fishmongers. But the League grew; in August it held its first London meeting and, as shortages became harder to tolerate in the post-war period, so the BHL increased its active membership by thousands, who called upon politicians to attend with urgency to the things that women

really

cared about. Tradesmen’s deliveries should be resumed at the earliest opportunity. Queues should be eliminated. Housewives had worked their fingers to the bone for nearly six long years, running their houses without help, clothing their families, battling with the mending. Among the League’s stated aims were ‘an ample supply of good food at a reasonable price’ and ‘the abolition of rationing and coupons … These are a threat to the freedom of the home’. Some branches even swore an oath not to buy expensive imported fruit like pineapples or tangerines.

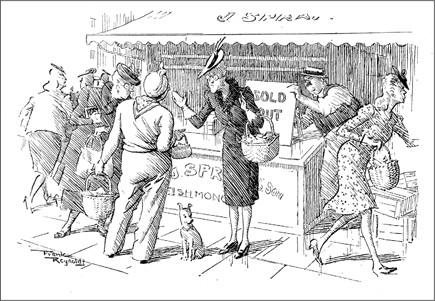

Enraged by obstructive fishmongers, middle-class women banded together to voice their frustration.

Mrs Lovelock and her League offer a fascinating case of the contradictory impulses that swayed women in the 1940s. Here we have a vigorous, independent-minded female activist, determined to mobilise women and make their voices heard in public. Her movement, with its parades and demonstrations, almost certainly drew inspiration from the tactics of the Suffragettes a generation earlier. But its aims, to begin with, were confined to getting butchers’ deliveries up and running and preventing exploitation by fishmongers. For Irene Lovelock’s world view, like those of many thousands like her, was unquestioningly traditional. A mother of three and pillar of her local church, she would have accepted the biblical portrayal of the virtuous wife: ‘for her price is far above rubies … She riseth also while it is yet night, and giveth meat to her household … Her children arise up and call her blessed.’ Her wifely identity was bred in the bone.