Microbrewed Adventures (5 page)

Message on a Bottle

Anchor Brewing Company

S

OMEWHERE

in the United States there is a unique, old and majestic pipe organ. Its spirit comes alive with the touch of human endeavor. It is a very special organ, because it keeps a secret hidden somewhere in its dark recessesâa very special message. Carved in small letters where no one will notice until perhaps another century is the simple message: “Relax. Don't worry. Have a homebrew.”

It's the message of a homebrewer who specializes in reconstructing these grand pipe organs.

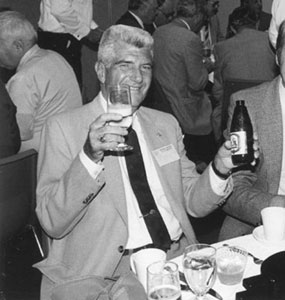

In 1986 I had the opportunity to tell this story to Fritz Maytag, president of the Anchor Brewing Company in San Francisco. We were both enjoying the beers of our choice. He cracked a small smile, glanced aside quickly and returned with a story of his own.

Fritz knew a very skilled and proud violinmaker who was in love. He'd confided to Fritz that written somewhere inside his most recent violin was a message that, in all probability, no one would notice for another thousand years. The message read: “I love you Susan.”

I wonder how many other people take pride in their skills and express their satisfaction in life's endeavors with small, unrewarded messages.

After my conversation with Fritz, I too became a bit inspired. My idea took seed at the Brewers Association of America Conference in 1986, where 14 breweries were represented. Wouldn't it be a great gesture to collect labels from each of the 14 participating breweries and have the CEO/president of each of these breweries sign the back side of everyone's label? In the end, each CEO would receive a collection of each label plus his or her label signed by 13 other CEOs.

I collected the blank labels and organized a sequential mailing. About six months later I received all of the signed labels and redistributed them. Fritz told me that he randomly inserted the signed labels into a bottling run of his Anchor Steam beer. I don't know what became of the others (Jerry Smart, Boulder Brewing Co.; Kendra Elliot, Dixie Brewing Co.; F. X. Matt II, F. X. Matt Brewing Co.; Fred Huber, Joseph Huber Brewing Co.; Paul Mayer, Jacob Leinenkugel Brewing Co.; Bill Smulowitz, The Lion Inc./Gibbons Stegmaier Brewery; Matthew Reich, New Amsterdam Brewing Co.; Bill Smith, Pabst Brewing Co.; Alice Victor, Savannah Beer Co.; George Korkmas, Spoetzel Brewery; Ken Shibilski, Stevens Point Brewing Co.; Dick

Yuengling, D. G. Yuengling and Son). I have my own collection framed on an office wallâa reminder of the passion that brewers share. A little bit of history. Some of those breweries and people are no longer with us.

I often wonder why microbrewing and homebrewing seem to be one of life's frequently celebrated endeavors, an endeavor that often prompts the best from individuals. Every day thousands of brewers leave small, unrewarded messages in each and every drop of beer they make. “Relax. Don't worry. Have my beer.” “I love you.” “I respect you.” “I appreciate that you enjoy my beer.” “You are simply the best.” “Thank you.”

Irish French Ale in the High Country

George Killian's Irish Red

F

ALLING IN LOVE

in France. A desire to marry and relocate to America. The relatives from Ireland who must grant permission. An impassioned relationship; a contract with the parents in Ireland and those that had kept her in France. Moving to America. Arrival. Culture shock. How to introduce her to friends? At first adhering to her origins, she slowly evolves and eventually becomes more American than she is French or Irish. In middle age, she is ignored, shelved for younger passions, but she still survives. Her roots have been misplaced, lost. But her pride persists; she is nominally supported and enjoys an active life as the unknown horizon of twilight approaches.

Â

IT HAS

all the intrigue of a movie romance. It began as a passionate love affair in the late 1970s and early 1980s with Irish Red Ale, brewed in France by the Pellforth Brewing Company, which had a license agreement with the Irish company George Killian Lett Brewing Company. Visiting France, Peter Coors of the Coors Brewing Company discovered this wonderfully complex red ale and considered how to brew it in America and successfully introduce it to American beer drinkers. He pursued his company's interest in the ale.

The years of intrigue and initial development were from about 1980 to 1982. During that period I was fortunate enough to be given a 250 ml bottle of George Killian's Irish Red Ale, brewed at the Pellforth brewery. It was a marvelously complex ale with only subtle fruitiness but with big notes of nuttiness and toasted malt, balanced with hop character. Not overly bitter, it was

smooth with quite a bit of drinkability. I recall a hint of floral aroma, perhaps from French countryside hops.

Its new home in America necessitated a makeover for the American public. In the early 1980s the pilot brewery at Coors occupied a relatively small space of about 5,000 square feet. Batch sizes were also small, at about 40 barrels. At the time, the brewery was producing over 15 million barrels of Coors, Coors Light and Herman Joseph. The Coors pilot brewery was the largest of the half-dozen microbreweries that existed in 1981.

I had earlier been introduced to the pilot brewery's head pilot brewer, Gil Ortega. One of the charges of the pilot brewery was product development. When homebrewers were invited to stop by and assess their experiments with “Killian's Red Ale,” we jumped at the opportunity.

When given creative choices, most brewers who call themselves masterbrewers will jump at the opportunity to develop new products. The spirit of beer passion was certainly evident in this tiny section of the Coors brewing factory.

There were many test batches, trying different malt types with varying degrees of toasting. At first different ale yeasts were used, producing full-flavored red ale with hints of fruitiness and, unfortunately, explosively active warm-temperature fermentations frothing out the tops of the fermenters. The brewers and homebrewers seemed to enjoy these earlier prototypes. So did several of the Coors staff, but operationally the brewery had other priorities. The fermentations certainly needed to be tamer, and warm-temperature fermentations would require refitting with accommodating equipment. Ale

yeast in a lager brewery made Coors nervous. And the looming marketing priority seemed to be “make us something that we can sell to our lager drinkers.”

Dave Thomas and Chuck Hahn worked on the original versions of Coors' Killian's Irish Red Ale

GEORGE KILLIAN'S IRISH RED ALE FROM PELLFORTH

Richly flavored with the subtle and romantic floral character of Santiam hops, this ale's long kettle boil accents the toasted and caramel character of malt. The beer's reddish glow is impassioned by the enthusiast who seeks original red ales. This recipe can be found in About the Recipes.

Killian's Irish Red Ale, originally introduced to the public at the first Great American Beer Festival in 1982, was indeed “top fermented” with ale yeast, but likely lagered at cooler temperatures to soften its complexity. I recall it being very well received. Most beer enthusiasts at the time were utterly astonished that Coors would be so bold as to brew distinctive red ale with a notable degree of complexity.

Time passed, and the company probably realized that if Killians were to survive, it had to increase its appeal to the average American beer drinker. In the following years, lager yeast replaced ale yeast and the complexity was reduced to accommodate the more popular tastes of the time.

Killian's has survived. It bears very little resemblance to the original 1982 recipe and it certainly has lost any connection, other than by name, to the red ale Peter Coors romanced in France. Yet it reminds me of the very beginnings of the emergence of microbrewed beer and of Coors's early passion for interesting, flavorful, complex beers.

Coors remains involved with the spirit of microbrewed beers. They produce Blue Moon Pumpkin Ale and Belgian-style Wheat Beer, and at the Sandlot (micro) Brewery at the Coors Stadium in downtown Denver they are brewing a wide variety of ales and lagers. There is also limited production of Barman, an all-malt German-style pilsener, originally brewed for the enjoyment of the Coors family and available at a half-dozen restaurants in the Denver-Boulder area in Colorado.

M

AY I PLEASE SPEAK

with Mr. Charlie Papazian?” asked a deep-voiced gentleman with a European accent.

“Hello, this is Charlie, can I help you?” I replied, with absolutely no idea that this was the beginning of an adventure I would recall for the rest of my life. I vividly remember the moment and recall it over and over. It was in July of 1982.

“Hello Mr. Papazian, my name is George Charalambous and I work for Anheuser-Busch in St. Louis. You have heard of the brewery?”

I liked this guy already. “Yes,” I replied with a nervous chuckle.

“May I call you Charlie?”

“Of course.”

“Charlie, I am organizing the annual joint meeting of District St. Louis Master Brewers Association of the Americas and the American Society of Brewing Chemists. I would like to invite you to speak at our meeting this coming April 14, 1983. We have heard you are doing some interesting things in Colorado. We cannot pay for your travel or accommodations, but we can offer you a free dinner.”

George Charalambous

I hesitated a moment, wondering a big “why?” “What would you want me to discuss?” I replied.

“I understand you have an association and some of your members are making homebrew and have started small microbreweries. I think it would be interesting to hear about them and taste some of their beers.”

This was my first contact with the “King,” Anheuser-Busch. I accepted knowing I had nine months to think about what to say. The adventure had begun.

One week later, a very enthusiastic George Charalambous called again. “Charlie, I have talked to some of my colleagues and I would like to ask whether you will consider making a batch of homebrew that could be served at the meeting.”

I knew I could make good homebrew, but I silently gasped nevertheless. I drew out the first word of my reply, trying to buy time. “Welllllllll,” lingering a moment, “yes I can⦔

Before I could continue, George raised his voice in excitement. “This is wonderful! You will have to tell me what you might brew after you have had time to think about it.”

“George, who will be at this meeting?”

“Professional brewers and production engineers and scientists from Anheuser-Busch; Falstaff, which is across the river; other professionals from the Midwest and manufacturers from Europe. We have a lot of fun and there's always plenty of beer.”

I did not get a good night's sleep that evening, as I wondered, “Where is all this going? Am I going to be able to make a beer that is up to their standards? Will they like my homebrew? Am I crazy?” Evidently I was.

Two weeks later George called again. There was excitement in his voice exceeding the pitch of the previous conversation by leaps and bounds. “Charlie, I have wonderful news⦔

“Uh ohhhhh,” I thought to myself as I fumbled for the imaginary seat belt on my office chair.

“Charlie I have talked to Ball Metal Container Corporation; you know, they make aluminum cans for us and they have agreed to supply us with cans to put your homebrew in. We will have the two logos of our professional associations as well as the logo of your American Homebrewers Association and your names as president of each organization. This will be great, Charlie.”

Now came the hard part. “George, how will you get the beer into cans?” I meekly asked.

“We will send you empty kegs, and after you have filled them we will ship them to St. Louis.”

I wondered if George realized that I was a homebrewer, making beer in

61

/2-gallon carboys fermenting under my kitchen table. “Howâ¦muchâ¦will youâ¦uhhhâ¦ahhhâ¦need, George?”