Microbrewed Adventures (4 page)

Process.

German-style Altbiers come immediately to mind. Warm fermentation and cold lagering are the conditions that precede all Altbiers. Without employing this process, which imparts some unique attributes to their overall quality, Altbiers could just as well be another bitter or sweet brown ale or a dark lager. Warm fermentâcold lager is the most important defining basis of this enjoyable brew.

Packaging.

This is a tricky one. Can packaging alone define the basis of a style? As beer enthusiasts we'd hate to consider it, but the realities of the beer world may preclude our own preferences. Let's consider many of the sweet fruit lambics that are making their way into the market. They simply could not exist without special considerations during packaging; sweet fruit juice or flavoring is added at packaging time. The beer is then pasteurized to prevent fermentation in the bottle, a process identical to the making of some classic English-style sweet stouts. Millions enjoy these sweet fruit beers and sweet stouts. Packaging more than anything else is the basis of these styles, more so than the specifications of malt, hops and yeast. Would you agree?

Special ingredients.

Herein lies the beer that may not be considered classic by most beer enthusiastsâyet. In this day and age, special ingredients have come to overwhelm the character of many beers. Belgian Wit (wheat or white) beers almost qualify for consideration on this basis. Their unique

blend of orange peel and coriander and the quality of the yeast seem to be the principal basis of Belgian-style Wit beer. Chili beer, pumpkin beer, spiced holiday-cheer beer, cranberry beer and cherry beer all may represent a style whose basis is a specialty ingredient. Perhaps special ingredients are a catchall second-string basis for all those beers that are in their early stages of evolution. We don't know which of the first seven characteristics to categorize them underâ

yet

.

Say you are considering 30 or 40 other classic styles of beer. Under which category would you place them? And why would I want to go through this exercise anyway? It helps me better understand what and why I am brewing. Brewing as a craft involves these kinds of thought processes. It inspires a thirst. If I didn't think about these kinds of things, I'd be pumping out “just” beer. I'm not into that kind of brewing.

The downside of thinking about the essence of brewing is that it can get downright confusing. I especially get confused after relaxing and enjoying one of my own homebrews, homebrews conceived and concocted from creative cauldrons of kettles and mind. On November 26, 1973, I brewed my first honey lager, a beer brewed with 40 percent honey. My friends thought it normal that I waved real monkey hair over the inoculated wort; but the weird thing was using honey in a beer. No doubt honey had been used in beer way before I ever thought of it, but the fact is I had never heard of such a thing. Thus was born Rocky Raccoon's Honey Lager, and as “Rocky met his match and said, âDoc it's only a scratch,'” we “proceeded to lie on the table.”

Yes, it was strange; so were my fruit beers, pale ales and lagers with pounds of fresh fruit added. They were considered “weird” beers, fun, tasty, but not seriously considered by any professionals, unless they were microbrewers.

Michael Jackson, at our 1986 American Homebrewers Conference, thought I'd really gone nuts when I introduced my commemorative conference beer. It was called Blitzweizen Honey Steam Barley Wine Lager. My intention was and still is

not

to make fun of beer traditions, but to peer over the edge and goose the creative possibilities. I have to admit there was no one basis upon which I brewed this beer. It was, rather, a celebration of all styles.

Little does Michael know that he is in part responsible for one of my beer style “gooses,” pushing the stylistic envelope. It was at one of the Philadelphia Book and the Cook festivities, where I was handed an absolutely delicious locally brewed imperial stout. With that in hand I was invited to attend Michael's beer tasting being held in the adjoining hall. I quietly entered in the middle of his presentation, happening to sit among a few homebrewers. I still

had quite a bit of tasty imperial stout in hand. Michael was halfway through his beer-tasting session and pouring Celis White, a light Belgian-style wheat beer spiced with coriander and Curação orange peel.

I looked all about me, pondering the Egyptian mummies and fantastic architecture of the hall. Then, as the ancient spirits swirled around the room, I had an impulse to create and go beyond what everyone in the room was tasting. Before I knew what I had done I was staring at a creation of half Celis White and half imperial stout. I sipped, smiled and shared it with the homebrewers sitting next to me. I think they agreed, but whether or not they did was irrelevantâI thought it had GREAT potential as a new beer. It was a new idea and, as I realize now, its basis was simply special ingredients, with the combination of Belgian traditions. The notion immediately became part of my inventive brewing plans.

Later, in May 1995, I traveled and tasted my way through Belgium. I fortified the knowledge I already had about Belgian ales and specialty beers. I brought the spirit of Belgian beer back to my homebrewery, and in June of 1995, Felicitous Belgian Stout was born. It was a beer I had never tasted before, except in my mind. There was no such style in Belgium.

Why do I call it Belgian stout? I brewed it with my new appreciation and knowledge of Belgian brewing traditions. If there were ever to be Belgian stout, what would it be? I considered the question seriously. It would be strong. Goldings-type hops would be used. A warm ferment would comfort the yeast. And the flavor and aroma of noble Saaz and Hallertauer would subtly finesse an already complex beer.

FELICITOUS STOUT

So what is it like? Felicitous Belgian Stout is a 6½ to 7 percent (I'll be pushing the higher end next time I brew this) alcohol by volume, very dark stout without the sharpness of roasted malt. The roasted malts and barley are mellowed and lightened by the overriding symphonic combination of coriander and orange peel. The floral and earthy character of Saaz and Hersbucker Hallertauer hops lay a foundation of beer quality upon which the sparkle of spice rides. The Vienna and crystal malt help produce an overall malty character without being excessively full bodied. Fully fermentable honey boosts the alcohol while contributing unique fermented character to the beer, much as candi sugar would had it been used. This recipe can be found in About the Recipes.

If I'd had candi sugar on the day I had chosen to impulsively brew Felicitous Belgian Stout, I would have used it, as the Belgians so often do. Instead, honey would have to do on this inaugural occasion. Many Belgian types of ale possess the flavor and aromatic character of crushed coriander seed and Curação orange peel.

Banana aroma and flavor are also part of the character of many Belgian ales, especially the stronger types. The banana is a byproduct of certain strains of yeast usually fermented at 70 to 80 degrees F. While I can appreciate these banana esters in certain ales, I chose not to design the stout with this in mind, but you may do so with your choice of yeast. Wheat could have been used in the formulation, really authenticating the original half-and-half mixture of imperial stout and Celis White I had conceived in Philadelphia, but then again I took homebrewed liberty in deciding not to formulate with wheat (but then again, you may, if you wish).

Brewery in a Goat Shed and The King Wants a Beer

T

HE

1980

S

were a busy time for me and for microbreweries. I put all my energies toward building up the American Homebrewers Association, the Association of Brewers (now called the Brewers Association) and the Great American Beer Festival. At the same time, many landmark breweries were getting their start. These were adventurous times when doctors, airline pilots, computer programmers, lawyers, teachers, social workers, salespeople and many other professionals were giving up their jobs, risking it all to pursue their passion for beer. Theirs was a belief that Americans deserved the opportunity for choice, flavor and diversity. The idea of great full-flavored lager and ale had captured a grassroots following. All of the microbrewed beer brewed in the 1980s didn't amount to even a drop in the bucketâit was more like a wisp of vapor in proportion to the 6.2 billion gallons of light lager beer enjoyed by Americans each year. But everyone involved felt the excitement of being a pioneer on the frontier of a movement that was sure to win over the beer enthusiast who savored the flavor of real beer. Here are a few stories from that time.

Brewery in a Goat Shed

Boulder Brewing Company

F

OR THE FEW INDIVIDUALS

who were lucky enough to have visited the original Boulder Brewing Company, the brewery will always be remembered as having been started in a farmhouse goat shed in Hygiene, Colorado. Opened in 1980, the Boulder Brewing Company, now called the Boulder Beer Company, is the oldest surviving craft microbrewery in America.

The love of beer and homebrewing provided the inspirationâmicrobrewing at its essence. Founders Stick Ware, David Hummer and Al Nelson decided that after their 14th single-barrel test batch of bottle-conditioned homebrew they were ready to explore the legal aspects of going professional. It wasn't easy in those days to start a small brewery. Malt was available only in quantities measured by train car loads, hops were sold in bales weighing hundreds of pounds and fresh yeast cultures could be had only at great expense or through long overseas journeys from German and English brewing institutions. Getting a brewery license was an extreme challenge, as the government agencies in charge of regulating brewing laws were more experienced in dealing with million-barrel-size breweries. The hurdles to opening the Boulder Brewing Company in 1980 were unquestionably daunting but were overcome with microbrewing persistence and the assistance of the only other “local” brewery, the Coors Brewing Company (providing them with pale malt).

That three guys, homebrewing test batches, managed to acquire the necessary equipment, ingredients and permits to go professional is yet another fantastic tribute to the passion for microbrewing and beer. Their passion is, in my opinion, the only reason they succeeded.

Otto Zavatone (with hat) at the “Goat Shed” Brewery with Michael Jackson (right), Fred Eckhardt (center, right) and Al Andrews (left)

English-accented Boulder Pale Ale, Porter and Stout were their initial styles of ale, introduced by

original head brewer Otto Zavatone. Otto once jokingly described how he got the job of head brewer at the “goat-shed” brewery: “They told me I could be the brewmaster, except I had to build the brewery first!”

The beer was truly handcrafted in every way, filled with a gravity-fed bottling system and capped using a manual “homebrew” bottle capper. All the beers were refermented in the bottle, establishing natural carbonation. After moving to their current facility in the late 1980s Boulder's hand-bottling system was abandoned. Today's Boulder beers are of extraordinary quality, and their range of ales and lagers offer a variety of flavors for the beer impassioned. I'm particularly fond of their hoppy Hazed and Infused, a lupulinhead's daydream.

But there was something charmed about their goat-shed ales of the mid 1980s. Otto Zavatone and his successor, Tom Burns, managed to extract unique, full-bodied, full-flavored ales from their small 1,200-square-foot brewery.

I have ever since been drawn to very small breweries, with batch sizes of five barrels or less. There is something unique about beers from breweries of this size. Perhaps it's because of the scientific dynamics involved when brewing in small volumes. I often find myself tasting a new beer not knowing its origins and marveling at characteristics reminiscent of the earliest small microbreweries, only to discover that the beer was brewed in batches of five barrels or less. I'm content to believe that these qualities reflect the original passion of a brewer who started out small, with all the dreams of success dancing in their mind as they tended to every aspect of the beer's production.

1981

BOULDER CHRISTMAS STOUT

In 1981 I shared a unique Christmas stout brewed by Guinness of Ireland with future Boulder head brewer Tom Burns. We both fell in love with the stuff, and Tom was determined to create a similar beer for Boulder. In those years Guinness had a tradition of making a special batch of Christmas ale. Its original gravity would match the year it was made, so that in 1981 the original gravity of their Christmas stout was 1.081ânearly double the strength of traditional draft Guinness stout. Tom Burns's Boulder Brewing Company's Special Christmas stout is rich, malty, smooth, velvety, strong and warming, with a wonderful hop balance that is not overwhelmingly bitter. It was one of the original American-brewed extra-special strong Imperial stouts. This recipe can be found in About the Recipes.

Only a Brick Remained

Jim Koch, St. Louis and Boston Beer Company

I

T WAS IN

1985

that Samuel Adams Boston Lager washed over the microbrewed beer scene. Like an unsuspected wave, it drenched beer drinkers and was popularly received as an old European-style pilsener lager. That year, the company, only six weeks old, flew in 20 cases of its beer, barely in time for the opening of the Fourth Annual Great American Beer Festival. It took top honors, winning the 1985 festival's consumer preference poll. From that point on, the waves created by Samuel Adams Boston Lager continued to wash over the landscape of American beer drinkers. Within years it could be found wherever beer was sold, paving the way for the thousands of brands of microbrewed beer that were seeking enthusiasts.

The 1980s were difficult years for most microbrewers. Their passion was evidenced by the quality of their beer, but the established ways of America's beer distribution system have always been a major challenge for microbrewers and a frustration for beer lovers seeking a choice. Great beer was being microbrewed, but the system failed to provide beer drinkers the access to beers they were growing to love.

The founder of Boston Beer Company and creator of Samuel Adams was a homebrewer, entrepreneur and, some say, a marketing genius. He recognized that brewing a distinctive and delicious beer was not enoughâyou had to make it accessible to beer drinkers. In that he succeeded. His name is Jim Koch. His father was in the beer business, and his great-grandfathers were brewers.

There's a little-known fact about Jim Koch's family brewing history that he shares with few people. He shared it with me the year before he introduced his first “Sam Adams.”

We met in St. Louis in the fall of 1984. I was attending a Master Brewers Association of the Americas Conference and had taken the afternoon off to rendezvous with Jim and his father, Charles Joseph Koch, Jr. We drove from the conference center to the vicinity of Anheuser-Busch's brewery. “It's near here.” Jim said as he sat up with visible excitement in his posture. His father glanced up the side streets, hinting recognition.

We parked the car. After walking several blocks, Jim's father announced, “We've got to be close. I recall that the Anheuser-Busch smokestack was visible from the site.” Coming upon a vacant lot overgrown with

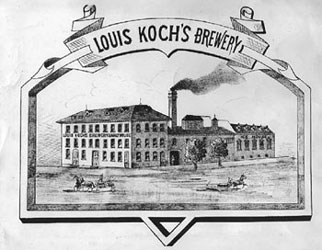

weeds and strewn with odd refuse, Jim and his father began examining the remnants of a low-lying stone wall paralleling the sidewalk. “I think this is it!” exclaimed Jim, his father agreeing but with a tone of doubt. We walked slowly onto the lot, avoiding rusty cans, the odd discarded tire and gnarly-looking weeds. We came upon a small indentation at the center and kicked away the loose dirt and rubbish. A smile crossed father and son's faces as the evidence revealed we had found what they were seeking: the site of the Louis Koch Lager Brewery, the home of the Koch familyâowned business that brewed between the 1860s and the 1880s. All that remained were a few stacked stones along the sidewalk and the wooden brick floor on which we were now standing.

On the southeast corner of Sydney and Buel Streeets, St. Louis

Louis Koch's Brewery. Courtesy Jim Koch.

Well preserved and black with the brewer's pitch used to line the inside of wooden barrels, the 4 Ã 6 Ã 2-inch wooden bricks was all that remained of the cooperage area of the brewery. It was the area where wooden barrels were built and reconditioned for beer.

Jim Koch and his father, Charles Joseph, in 1984 chipping away masonry souvenirs from the site of the Louis Koch's Brewery in St. Louis. The Anheuser-Busch Brewery is centered in the background. On the southeast corner of Sydney and Buel Streeets, St. Louis

Louis Koch's Brewery. Courtesy Jim Koch.

SAMUEL ADAMS

1880

Neither an American nor a European-style pilsener, Samuel Adams Boston Lager is a re-creation of a historical American-type golden, hinting-at-amber, lager beer. Full-flavored, with a delicate proportion of dark caramel malt complemented by the unique flavor and floral character of German-grown hops, it's every bit as refreshing as classic pilsener. The Louis Koch Lager Brewery created a beer of its time, forgotten until Jim Koch resurrected it. Here is a recipe that may approach today's Samuel Adams Boston Lager, as well as the lager at the family's 1880 brewery. This recipe can be found in About the Recipes.

We each took a brick as a souvenir and as we approached the car, Jim's gait quickened. He opened the trunk and took out a sledgehammer. Returning to the wall, he and his father wailed on the stone in the shadow of the world's largest brewing company. Pieces of the wall crumbled. The two men lifted a few chunks of foundation wall and placed them in the trunk of the car. And left the vacant lot to its destiny.

Since then I have heard Jim remind brewers several times that people DRINK the BEER. It is not a commodity, a label, an added flavor, nor market research. It has soul and heart. I would add, so do the people who make it. Jim has nurtured the new family brewery as one of the world's leading brewers of specialty craft beers in the true spirit of a microbrewery.

It's true, Samuel Adams Boston Lager started as a homebrew. I brewed the first batch in my kitchen in 1984 using a recipe of my great-great-great-grandfather's from the 1870sâ¦I fell in love with the taste of this beer. I thought that if I could taste this beer every day of my life, I'd be a happy man. That was my motivation for starting the Boston Beer Company.

âJ

IM

K

OCH, FOUNDING PRESIDENT

/CEO, B

OSTON

B

EER

C

OMPANY