Merlin's Booke (24 page)

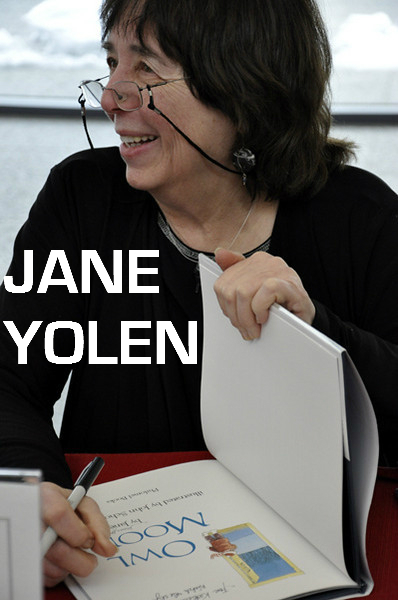

Authors: Jane Yolen

“Of course it is.”

“No. It isn't.”

“What did you see, Patti. Please.” McNeil's eyes narrowed and he leaned forward as if listening was an activity that suddenly took great physical energy.

“Well, the light of course, like Stevie says, only I thought it came

from

the box. And the prince doing his big act. But there was something more, something strange. I thought I saw a tree, as if it were projected from the box onto the screen. And then I smelled apple blossoms. The screen seemed, for a moment, to open as though it were a door that I could look through. That's where the tree was, behind the door. A whole orchard of apple trees in blossom. But it was just a momentary thing. A hallucination.”

“Or a slide projected from the back of the screen,” said Stevens. “We should check.”

“You

didn't see it,” McNeil pointed out.

“I was watching the prince.”

McNeil jammed his hands into his jacket pockets and stared at Patti. “Do you thinkâdo you

really

thinkâthe Prince of Wales would be party to such trickery?”

“What if he didn't know?” asked Stevens.

Patti shook her head. “What did you see, Mac?”

Stevens laughed. “Here it comes, lights, camera, action.”

McNeil looked at the door ahead where very ordinary daylight was drifting in motes through the opening. From outside came the sound of chanting. The protestors were still at it.

“Come on, Mac.

I

told. What did you see?”

Could he tell them that at the moment the box had opened, the ceiling and walls of the meeting room had dropped away? That they were all suddenly standing within a circle of Corinthian pillars under a clear night sky. That as he watched, behind the pillars one by one the stars had begun to fall. Could he tell them? Or more to the pointâwould they believe?

“Light,” he said. “I saw light. And darkness coming on.” He bit his lip. Merlin had been known as a prophet, a soothsayer, equal to or better than Nostradamus. But the words of seers have always admitted to a certain ambiguity. He put his hands on Patti's shoulders and stared at her. For a moment his eyes were those of a dying man's. Then he laughed.

“My darlings,” he said, “I have a sudden and overwhelming thirst. I want to make a toast to the earth under me and the sky above me. A toast to the arch-mage and what he has left us. A salute to Merlin:

ave magister.

Will you come?” If there was desperation in his voice, only he understood it. Desperationâand a last, wild, fierce, joyful grasping for life. He laughed again.

“What's so funny?” Patti and Steve asked together.

“Irony,” he said. “The kind that only the Celtic mind can truly understandâor love.”

After that he was silent and they had to follow him, still wondering, as he pushed through the door and into the aggressive light and the chantings of the crowd.

Well then, after many years had passed under many kings, Merlin the Briton was held famous in the world. He was a King and a prophet; to the proud people of the South Welsh he gave laws, and to the chieftains he prophesied the future.”

âVita Merlini

by Geoffrey of Monmouth

Let all who trust in hidden power

(The birth is in the stone)

Remember well the mage's hour:

Find it,

Make it,

Bind it,

Take it,

Touch magic, pass it on.

“The Ballad of the Mage's Birth” copyright © 1986 by Jane Yolen. First publication.

“The Confession of Brother Blaise” copyright © 1986 by Jane Yolen. First publication.

“The Wild Child” copyright © 1986 by Jane Yolen. First publication.

“Dream Reader” copyright © 1986 by Jane Yolen. First publication.

“The Annunciation” copyright © 1985 by Jane Yolen. First published in

Star*Line,

Science Fiction Poetry Association.

“The Gwynhfar” copyright © 1983 by Jane Yolen. First published in

TALES OF WONDER

(Shocken Books).

“The Dragon's Boy” copyright © 1985 by Jane Yolen. First published in

The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction

(Mercury Press).

“The Sword and the Stone” copyright © 1985 by Jane Yolen. First published in

The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction

(Mercury Press).

“Merlin at Stonehenge” copyright © 1985 by Jane Yolen. First published in

Star*Line,

Science Fiction Poetry Association.

“Evian Steel” copyright © 1985 by Jane Yolen. First published in

IMAGINARY LANDS

, edited by Robin McKinley (Ace Fantasy Books).

“In the Whitethorn Wood” copyright © 1984 by Jane Yolen. First published in

THE WHITETHORN WOOD AND OTHER TALES

(Triskell Press).

“Epitaph” copyright © 1986 by Jane Yolen. First publication.

“L'Envoi” copyright © 1986 by Jane Yolen. First publication.

I

N THE EIGHTIES

and nineties, I began writing a series of short stories and poems about Merlin and King Arthur because I'd been obsessed with the Arthurian mythos since I was a child.

Most of these stories and poems were first published singly in places like the

Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction

and

Asimov's Science Fiction

, or in anthologies. Only after I'd written and published several of them did I realize I had the makings of a collection.

That's when I really got serious about putting the stories together. Four of the stories became the basis for novels later on:

The Dragon's Boy

,

Sword of the Rightful King

, and two of the three books in the Young Merlin Trilogy all came directly from these stories. Plus, I have wanted to turn the story of the island women swordmakers into a graphic novel for years. Maybe it's time!

My friends all teased me about the title of this one, calling me “Merlin's bookie” and placing bets on who gets out of the book alive!

Jane Yolen

I was born in New York City on February 11, 1939. Because February 11 is also Thomas Edison's birthday, my parents used to say I brought light into their world. But my parents were both writers and prone to exaggeration. My father was a journalist; my mother wrote short stories and created crossword puzzles and double acrostics. My younger brother, Steve, eventually became a newspaperman. We were a family of an awful lot of words!

We lived in the city for most of my childhood, with two brief moves: to California for a year while my father worked as a publicity agent for Warner Bros. films, and then to Newport News, Virginia, during the World War II years, when my mother moved my baby brother and me in with her parents while my father was stationed in London running the Army's secret radio.

When I was thirteen, we moved to Connecticut. After college I worked in book publishing in New York for five years, married, and after a year traveling around Europe and the Middle East with my husband in a Volkswagen camper, returned to the States. We bought a house in Massachusetts, where we lived almost happily ever after, raising three wonderful children.

I say “almost,” because in 2006, my wonderful husband of forty-four yearsâProfessor David Stemple, the original Pa in my Caldecott Awardâwinning picture book,

Owl Moon

âdied. I still live in the same house in Massachusetts.

And I am still writing.

I have often been called the “Hans Christian Andersen of America,” something first noted in

Newsweek

close to forty years ago because I was writing a lot of my own fairy tales at the time.

The sum of my booksâincluding some eighty-five fairy tales in a variety of collections and anthologiesâis now well over 335. Probably the most famous are

Owl Moon

,

The Devil's Arithmetic

, and

How Do Dinosaurs Say Goodnight?

My work ranges from rhymed picture books and baby board books, through middle grade fiction, poetry collections, and nonfiction, to novels and story collections for young adults and adults. I've also written lyrics for folk and rock groups, scripted several animated shorts, and done voiceover work for animated short movies. And I do a monthly radio show called

Once Upon a Time

.

These days, my work includes writing books with each of my three children, now grown up and with families of their own. With Heidi, I have written mostly picture books, including

Not All Princesses Dress in Pink

and the nonfiction series Unsolved Mysteries from History. With my son Adam, I have written a series of Rock and Roll Fairy Tales for middle grades, among other fantasy novels. With my son Jason, who is an award-winning nature photographer, I have written poems to accompany his photographs for books like

Wild Wings

and

Color Me a Rhyme.

And I am still writing.

Ohâalong the way, I have won a lot of awards: two Nebula Awards, a World Fantasy Award, a Caldecott Medal, the Golden Kite Award, three Mythopoeic Awards, two Christopher Awards, the Jewish Book Award, and a nomination for the National Book Award, among many accolades. I have also won (for my full body of work) the World Fantasy Award for Lifetime Achievement, the Science Fiction Poetry Association's Grand Master Award, the Catholic Library Association's Regina Medal, the University of Minnesota's Kerlan Award, the University of Southern Mississippi and de Grummond Children's Literature Collection's Southern Miss Medallion, and the Smith College Medal. Six colleges and universities have given me honorary doctorate degrees. One of my awards, the Skylark, given by the New England Science Fiction Association, set my good coat on fire when the top part of it (a large magnifying glass) caught the sunlight. So I always give this warning: Be careful with awards and put them where the sun don't shine!

Also of noteâin case you find yourself in a children's book trivia contestâI lost my fencing foil in Grand Central Station during a date, fell overboard while whitewater rafting in the Colorado River, and rode in a dog sled in Alaska one March day.

And yesâI am still writing.

At a Yolen cousins reunion as a child, holding up a photograph of myself. In the photo, I am about one year old, maybe two.

Sitting on the statue of Hans Christian Andersen in Central Park in New York in 1961, when I was twenty-two. (Photo by David Stemple.)

Enjoying Dirleton Castle in Scotland in 2010.