Men Explain Things to Me (9 page)

Read Men Explain Things to Me Online

Authors: Rebecca Solnit

Tags: #Feminism & Feminist Theory, #Current Affairs, #Imperialism, #Political Science, #Women's Studies, #Download-Ebook Farm, #Social Science

By now you’ve noticed that Woolf says “I don’t know” quite a lot.

“Killing the Angel of the House,” she says further on, “I think I solved. She died. But the second, telling the truth about my own experiences as a body, I do not think I solved. I doubt that any woman has solved it yet. The obstacles against her are still immensely powerful—and yet they are very difficult to define.” This is Woolf’s wonderful tone of gracious noncompliance, and to say that her truth must be bodily is itself radical to the point of being almost unimaginable before she had said it. Embodiment appears in her work much more decorously than in, say, Joyce’s, but it appears—and though she looks at ways that power may be gained, it is Woolfian that in her essay “On Being Ill” she finds that even the powerlessness of illness can be liberatory for noticing what healthy people do not, for reading texts with a fresh eye, for being transformed. All Woolf’s work as I know it constitutes a sort of Ovidian metamorphosis where the freedom sought is the freedom to continue becoming, exploring, wandering, going beyond. She is an escape artist.

In calling for some specific social changes, Woolf is herself a revolutionary. (And of course she had the flaws and blind spots of her class and place and time, which she saw beyond in some ways but not in all. We also have those blind spots later generations may or may not condemn us for.) But her ideal is of a liberation that must also be internal, emotional, intellectual.

My own task these past twenty years or so of living by words has been to try to find or make a language to describe the subtleties, the incalculables, the pleasures and meanings—impossible to categorize—at the heart of things. My friend Chip Ward speaks of “the tyranny of the quantifiable,” of the way what can be measured almost always takes precedence over what cannot: private profit over public good; speed and efficiency over enjoyment and quality; the utilitarian over the mysteries and meanings that are of greater use to our survival and to more than our survival, to lives that have some purpose and value that survive beyond us to make a civilization worth having.

The tyranny of the quantifiable is partly the failure of language and discourse to describe more complex, subtle, and fluid phenomena, as well as the failure of those who shape opinions and make decisions to understand and value these slipperier things. It is difficult, sometimes even impossible, to value what cannot be named or described, and so the task of naming and describing is an essential one in any revolt against the status quo of capitalism and consumerism. Ultimately the destruction of the Earth is due in part, perhaps in large part, to a failure of the imagination or to its eclipse by systems of accounting that can’t count what matters. The revolt against this destruction is a revolt of the imagination, in favor of subtleties, of pleasures money can’t buy and corporations can’t command, of being producers rather than consumers of meaning, of the slow, the meandering, the digressive, the exploratory, the numinous, the uncertain.

I want to end with a passage from Woolf that my friend the painter May Stevens sent me after writing it across the text of one of her paintings, a passage that found its way into

A Field Guide to Getting Lost

. In May’s paintings, Woolf’s long sentences are written so that they flow like water, become an elemental force on which we are all swept along and buoyed up. In

To the Lighthouse

, Woolf wrote:

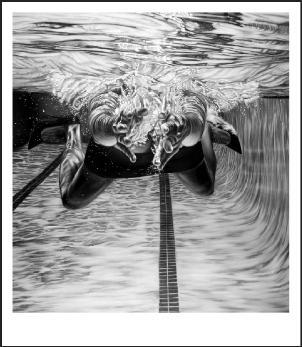

For now she need not think about anybody. She could be herself, by herself. And that was what now she often felt the need of—to think; well, not even to think. To be silent; to be alone. All the being and the doing, expansive, glittering, vocal, evaporated; and one shrunk, with a sense of solemnity, to being oneself, a wedge-shaped core of darkness, something invisible to others. Although she continued to knit, and sat upright, it was thus that she felt herself; and this self having shed its attachments was free for the strangest adventures. When life sank down for a moment, the range of experience seemed limitless. . . . Beneath it is all dark, it is all spreading, it is unfathomably deep; but now and again we rise to the surface and that is what you see us by. Her horizon seemed to her limitless.

Woolf gave us limitlessness, impossible to grasp, urgent to embrace, as fluid as water, as endless as desire, a compass by which to get lost.

chapter 7

Pandora’s Box and the Volunteer Police Force

2014

The history of women’s rights and feminism is often told as though it were a person who should already have gotten to the last milestone or has failed to make enough progress toward it. Around the millennium lots of people seemed to be saying that feminism had failed or was over. On the other hand, there was a wonderful feminist exhibition in the 1970s entitled “Your 5,000 Years Are Up.” It was a parody of all those radical cries to dictators and abusive regimes that your [fill in the blank] years are up. It was also making an important point.

Feminism is an endeavor to change something very old, widespread, and deeply rooted in many, perhaps most, cultures around the world, innumerable institutions, and most households on Earth—and in our minds, where it all begins and ends. That so much change has been made in four or five decades is amazing; that everything is not permanantly, definitively, irrevocably changed is not a sign of failure. A woman goes walking down a thousand-mile road. Twenty minutes after she steps forth, they proclaim that she still has nine hundred ninety-nine miles to go and will never get anywhere.

It takes time. There are milestones, but so many people are traveling along that road at their own pace, and some come along later, and others are trying to stop everyone who’s moving forward, and a few are marching backward or are confused about what direction they should go in. Even in our own lives we regress, fail, continue, try again, get lost, and sometimes make a great leap, find what we didn’t know we were looking for, and yet continue to contain contradictions for generations.

The road is a neat image, easy to picture, but it misleads when it tells us that the history of change and transformation is a linear path, as though you could describe South Africa and Sweden and Pakistan and Brazil all marching along together in unison. There is another metaphor I like that expresses not progress but irrevocable change: it’s Pandora’s box, or, if you like, the genies (or djinnis) in bottles in the

Arabian Nights

. In the myth of Pandora, the usual emphasis is on the dangerous curiosity of the woman who opened the jar—it was really a jar, not a box the gods gave her—and thereby let all the ills out into the world.

Sometimes the emphasis is on what stayed in the jar: hope. But what’s interesting to me right now is that, like the genies, or powerful spirits, in the Arabic stories, the forces Pandora lets out don’t go back into the bottle. Adam and Eve eat from the Tree of Knowledge and they are never ignorant again. (Some ancient cultures thanked Eve for making us fully human and conscious.) There’s no going back. You can abolish the reproductive rights women gained in 1973, with

Roe v. Wade

, when the Supreme Court legalized abortion—or rather ruled that women had a right to privacy over their own bodies that precluded the banning of abortion. But you can’t so easily abolish the idea that women have certain inalienable rights.

Interestingly, to justify that right, the judges cited the Fourteenth Amendment, the constitutional amendment adopted in 1868, as part of the post–Civil War establishment of rights and freedoms for the formerly enslaved. So you can look at the antislavery movement—with powerful female participation and feminist repercussions—that eventually led to that Fourteenth Amendment, and see, more than a century later, how that amendment comes to serve women specifically. “The chickens come home to roost” is supposed to be a curse you bring on yourself, but sometimes the birds that return are gifts.

Thinking Out of the Box

What doesn’t go back in the jar or the box are ideas. And revolutions are, most of all, made up of ideas. You can whittle away at reproductive rights, as conservatives have in most states of the union, but you can’t convince the majority of women that they should have no right to control their own bodies. Practical changes follow upon changes of the heart and mind. Sometimes legal, political, economic, environmental changes follow upon those changes, though not always, for where power rests matters. Thus, for example, most Americans polled would like to see economic arrangements very different from those we have, and most are more willing to see radical change to address climate change than the corporations that control those decisions and the people who make them.

But in social realms, imagination wields great power. The most dramatic arena in which this has taken place is rights for gays, lesbians, and transgender people. Less than half a century ago, to be anything but rigorously heterosexual was to be treated as either criminal or mentally ill or both, and punished severely. Not only were there no protections against such treatment, there were laws mandating persecution and exclusion.

These remarkable transformations are often told as stories of legislative policy and specific campaigns to change laws. But behind those lies the transformation of imagination that led to a decline in the ignorance, fear, and hatred called homophobia. American homophobia seems to be in just such a steady decline, more a characteristic of the old than the young. That decline was catalyzed by culture and promulgated by countless queer people who came out of the box called the closet to be themselves in public. As I write this, a young lesbian couple has just been elected as joint homecoming queens at a high school in Southern California and two gay boys were voted cutest couple in their New York high school. This may be trivial high-school popularity stuff, but it would have been stunningly impossible not long ago.

It’s important to note (as I have in “In Praise of the Threat” in this book), that the very idea that marriage could extend to two people of the same gender is only possible because feminists broke out marriage from the hierarchical system it had been in and reinvented it as a relationship between equals. Those who are threatened by marriage equality are, many things suggest, as threatened by the idea of equality between heterosexual couples as same-sex couples. Liberation is a contagious project, speaking of birds coming home to roost.

Homophobia, like misogyny, is still terrible; just not as terrible as it was in, say, 1970. Finding ways to appreciate advances without embracing complacency is a delicate task. It involves being hopeful and motivated and keeping eyes on the prize ahead. Saying that everything is fine or that it will never get any better are ways of going nowhere or of making it impossible to go anywhere. Either approach implies that there is no road out or that, if there is, you don’t need to or can’t go down it. You can. We have.

We have so much further to go, but looking back at how far we’ve come can be encouraging. Domestic violence was mostly invisible and unpunished until a heroic effort by feminists to out it and crack down on it a few decades ago. Though it now generates a significant percentage of the calls to police, enforcement has been crummy in most places—but the ideas that a husband has the right to beat his wife and that it’s a private matter are not returning anytime soon. The genies are not going back into their bottles. And this is, really, how revolution works. Revolutions are first of all of ideas.

The great anarchist thinker David Graeber recently wrote,

What is a revolution? We used to think we knew. Revolutions were seizures of power by popular forces aiming to transform the very nature of the political, social, and economic system in the country in which the revolution took place, usually according to some visionary dream of a just society. Nowadays, we live in an age when, if rebel armies do come sweeping into a city, or mass uprisings overthrow a dictator, it’s unlikely to have any such implications; when profound social transformation does occur—as with, say, the rise of feminism—it’s likely to take an entirely different form. It’s not that revolutionary dreams aren’t out there. But contemporary revolutionaries rarely think they can bring them into being by some modern-day equivalent of storming the Bastille. At moments like this, it generally pays to go back to the history one already knows and ask: Were revolutions ever really what we thought them to be?

Graeber argues that they were not—that they were not primarily seizures of power in a single regime, but ruptures in which new ideas and institutions were born, and the impact spread. As he puts it, “the Russian Revolution of 1917 was a world revolution ultimately responsible for the New Deal and European welfare states as much as for Soviet communism.” Which means that the usual assumption that Russian revolution only led to disaster can be upended. He continues, “The last in the series was the world revolution of 1968—which, much like 1848, broke out almost everywhere, from China to Mexico, seized power nowhere, but nonetheless changed everything. This was a revolution against state bureaucracies, and for the inseparability of personal and political liberation, whose most lasting legacy will likely be the birth of modern feminism.”