Margaret Fuller (88 page)

Authors: Megan Marshall

and housewives’ “littleness,”

[>]

and “supersensuous connection,”

[>]

,

[>]

and Fuller on life scope,

[>]

Fuller on reform of,

[>]

and Fuller’s Conversations group,

[>]

,

[>]

–

[>]

,

[>]

,

[>]

and Fuller’s farewell in

Tribune,

[>]

and Fuller’s life, xvi–xvii,

[>]

,

[>]

,

[>]

in Fuller’s “Magnolia” story,

[>]

–

[>]

Fuller’s perception sharpened by European tour,

[>]

and goals in Greene Street School,

[>]

–

[>]

and “The Great Lawsuit,”

[>]

,

[>]

,

[>]

(see also “Great Lawsuit, The. Man

versus

Men. Woman

versus

Women”)

and “Great Lawsuit” expanded (

Woman in the Nineteenth Century

),

[>]

–

[>]

,

[>]

–

[>]

,

[>]

(

see also Woman in the Nineteenth Century

)

and men’s reaction to women of verbal superiority,

[>]

Mickiewicz on,

[>]

Ripley essay on,

[>]

–

[>]

and Transcendental Club,

[>]

–

[>]

woman ambassador foreseen,

[>]

Women’s suffrage movement, Fuller seen as head of,

[>]

–

[>]

Woolf, Virginia,

[>]

Worcester State Lunatic Hospital,

[>]

Words of a Believer

(Lamennais),

[>]

Wordsworth, William,

[>]

,

[>]

,

[>]

,

[>]

,

[>]

Young Lady’s Friend, The (Farrar),

[>]

,

[>]

Zeluco (Moore),

[>]

Zinzendorf, Count and Countess,

[>]

Zoroastrianism, and “Orphic Sayings,”

[>]

Part 1

Origins 1746–1803

1. Matriarch

A

SIDE FROM ONE STIFFLY POSED SILHOUETTE, THE ONLY SURVIVING

likeness of Mrs. Elizabeth Palmer Peabody is a small pencil drawing Sophia made in one of her sketchbooks in the early 1830s. By this time Sophia and her sisters were all in their twenties and their mother was approaching sixty. Eliza, as she was known to her family, had given birth to four daughters (one died in infancy) and three sons, moved her family in and out of nearly a dozen different houses, never owning one of them, and devoted most of her waking hours to augmenting her husband’s meager income by teaching or tutoring young girls. There are hints of that life of hard work in the set of Mrs. Peabody’s jaw, in her tired eyes. But the “Mamma” Sophia chose to depict is a woman apparently free of daily burdens. We see her in profile, settled happily at a table, hair tucked back into a lace-trimmed cap, reading a book, with a vase of flowers to complete the tableau.

A hint of a smile plays about Mrs. Peabody’s face, reminding us that she was not alone in the room. Was the affectionate look intended for Sophia or her sisters? Sophia manages to suggest a parlor scene with, perhaps, the rest of the family gathered outside the frame, reading or talking. The drawing could have been captioned with Mrs. Peabody’s words of advice, written about the same time the sketch was made, when the family had come to believe that Sophia would never be well enough to marry or to leave home. “The love which settles down upon the household circle tho’ more quiet, is deeper, steadier, more efficient than any other love,” she counseled Sophia. “Anchor your soul on domestic love.”

Sophia liked to draw spare, almost stylized sketches of her friends and family inspired by the English artist John Flaxman’s illustrations of Greek myths, then popular with the Boston intelligentsia. She gives us just the outlines

of her mother’s short cape—it must have been a chilly New England spring day—and a long sleeve. But the simple props she selected for her mother’s portrait were as significant as Diana’s arrows or Pandora’s box in a Flaxman line drawing. Both book and flowers were signs of high culture and feminine refinement. Yet Mrs. Peabody was no dilettante. She was a published poet and read widely and critically all her life, passing along her passion for literature to her daughters, who made books and learning the central focus of their own lives. She prized flowers and—when she had the time, when she had a garden, and when her husband’s ridicule didn’t stop her—took long walks in search of unusual specimens to transplant to her own flower beds. Sophia sketched her mother as she wanted to be seen, and as Sophia wanted to remember her: at peace and surrounded by the elements of her favorite occupations. A decade after she drew this sketch, a month after she left home with her new husband, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Sophia was still trying to think of her mother this way. “I could see in you the image of a perfect woman,” she wrote to her mother, recollecting her years at home. But she couldn’t keep herself from adding: “through all the shadows of the world over you.”

Sophia’s sketch of her mother, Eliza Peabody

There were shadows. The family’s longtime physician and friend Dr. Walter Channing, brother of the celebrated Unitarian minister William Ellery Channing, once wrote of Mrs. Peabody that “in memory I always see her smiling,” yet “her smile was always to me like the shining out of an angel’s face from behind a mask where brave struggles with heavy sorrows had left deep imprints of mortality.” Sophia and her sisters were called on throughout their lives to puzzle out and then to soothe their mother’s heavy sorrows, to vindicate her defeats with their accomplishments, to compensate for her troubled marriage with grand passions of their own. Like many American women who extolled the virtues of female domesticity during the first half century following the Revolution, Mrs. Peabody sought to “anchor” her soul on “domestic love” because it had always been elusive.

For Mrs. Peabody there were private troubles to contend with, but these were also years when men and women jockeyed for power in households throughout the thirteen states after independence was declared. During the 1780s, the decade of Eliza Peabody’s childhood, families were reunited and women took control of the home as their “sphere.” But for some women, authority in the home seemed a good deal less than the reward American men had given themselves for wartime service: the exclusive right to rule in public life. It was possible for a woman to convince herself that raising the sons of the Republic was a worthy task; and women used the ideology of “Republican Motherhood” to win new privileges, particularly the right to an education, and later the opportunity to work as teachers and reformers. But for some daughters of independence—girls who, like Eliza, grew up as the children or sisters of soldiers, who had helped run farms and businesses while the men of the family fought the war—power at home was never quite enough, and the very domestic tranquility they later espoused as wives and mothers proved hard to come by.

Mrs. Peabody once wrote to her daughter Mary, “I long for means and power ... but I wear peticoats and can never be Governor ... nor alderman, Judge or jury, senator or representative—so I may as well be quiet—content with intreating the Father of all mercies.” Yet Mrs. Peabody could never silence her longings, and she passed them on to her daughters in the form of stories about her ancestors—stories intricately entwined with the early history of the nation, told and retold until they became touchstones for the three girls who would grow into women of extraordinary energy and influence. Through her “patriotic mother,” her oldest daughter, Elizabeth, liked to say that she had been “educated by the heroic age of the country’s history.” Not a little of that heroism was her mother’s, as she struggled to overcome a family heritage of betrayal and loss.

2. Legacies

L

IKE THE SMILE ON HER FACE IN SOPHIA’S DRAWING, THERE WAS A

surface history, a tale of brave deeds in grander times, that Mrs. Peabody recited proudly, usually omitting the sorry ending. She even wrote a novel adapting and improving on the events of her family’s past. The novel was never published, but it remained part of the Peabody family’s treasured papers for a century after it was written, keeping alive for each new generation the stories that guided this embattled family of women through the early decades of the American Republic.

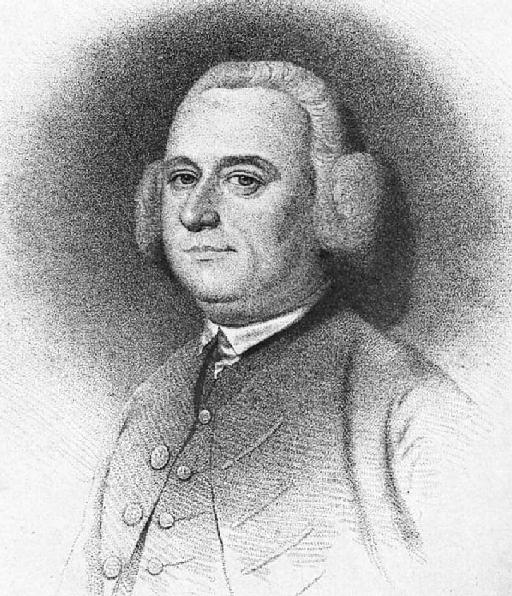

She was born Elizabeth Palmer, the third of nine children of wealthy Massachusetts colonials. The wealth came from her grandfather, General Joseph Palmer, whom she remembered from early childhood as “more like an old fashioned English country gentleman, than any one” of his time and place. The general was so beloved by all who knew him, even animals, it was said that when he was away from home his cat tried to climb onto the shoulder of the John Singleton Copley portrait of him that hung in his library.

Yet Eliza scarcely knew the luxury she might have inherited. Family life was so fractured by the time she was born that neither birth nor baptism, if there was one, was ever recorded. The month was February, but the year might have been 1776, 1777, or 1778, according to conflicting family documents. These were the war years—soon to be the dark years of the war for the Palmer family—when town records were unevenly kept.

In sunnier times, the Palmers lived in a large square house made of oak and stone, with four enormous chimneys rising up at each corner, perched on a hill above a pretty cove known as Snug Harbor in Germantown, thirteen miles south of Boston. Not quite a mansion, the house nevertheless became known as Friendship Hall in the decades at midcentury when the benevolent General Palmer oversaw “a settlement of free and independent artisans and manufacturers” who operated his chocolate mills; spermaceti, salt, and glass works; and a factory for weaving stockings. In fact, Palmer owned all of Germantown, which occupied a small peninsula jutting out into Boston Harbor at the northernmost corner of Braintree, a town that would later become famous for its native sons John Hancock and John Adams.

General Joseph Palmer, engraving from the Copley portrait

Emigrating from England in 1746, the visionary Palmer had seen fit to house his workmen and their families—most of them newly arrived from Europe as well—in several stone buildings near his factories, making the Germantown settlement a commercial version of the Puritans’ earlier “city upon a hill.” And he realized his plan nearly a century before the founding of New England’s model industrial towns at Lawrence and Lowell. Although she never lived there, Eliza would remember Friendship Hall best of all the Germantown buildings, with its polished mahogany floors and banisters, its wallpaper painted with scenes of classical ruins, its hillside planted with fruit trees leading down to Snug Harbor. There, she knew, “Grandpapa Palmer” had once entertained an emerging local aristocracy made up of Adamses, Palmers, and Quincys—the family that would produce three mayors of Boston, one of whom went on to become a president of Harvard College, and for whom this portion of Braintree was later renamed.