Margaret Fuller (20 page)

Authors: Megan Marshall

Still, Waldo’s sporadic expansiveness—and Margaret’s need—brought a new intensity to the relationship. Once she left for Providence, he began addressing her as “My dear friend” rather than “My dear Miss Fuller” in letters; through the wearying spring of 1838, Margaret progressed from signing herself “Devoutly, if not worthily yours, S. M. Fuller” to the fervent “Always yours, S.M.F.”

When Cary Sturgis, now nineteen and ready to defy her father, made a visit to Concord that summer, Waldo was grateful to Margaret for bringing them together: “For a hermit I begin to think I know several very fine people.”

Margaret was one of them, and when the opportunity presented itself, he wanted her close by. At the end of summer, when Margaret confided her hope to leave teaching before winter, Waldo insisted she spend the following year in Concord. “Will you commission me to find you a boudoir,” he offered, “or, much better, will you defy my awkwardness & come & sit down in our castle, summon the village before you & find an abode at your leisure? I really hope you mean to come & study here. And to come now.”

Waldo needed Margaret too, reluctant as he was to partake of her language of passionate friendship.

Finally illness rescued Margaret. By the fall of 1838 she felt exhausted nearly all the time and missed more days of teaching. She sent for her sister, Ellen, to stay with her and then to serve as her substitute for several weeks. Traveling to Boston, Margaret consulted Dr. Walter Channing, Reverend Channing’s brother and the most respected doctor to women in Boston. In early November, “I heard with unspeakable pain Dr. Channing’s opinion that I must go away.” She would not go away to Concord, but to Groton—“to the quiet of home, and the care of my mother.” She felt sure of a cure there—“I am by nature energetick and fearless; if I should recover my natural tone of health and spirits, I shall not dread labor nor shrink from meeting a circle of strangers as I do now.” Her mother had at last sold the property, and the family needed to vacate the premises by April. “I do not know what we shall do,” Margaret had to admit. “But I do not look beyond.” It was enough to count on “these three months of peace and seclusion after three years of toil, restraint and perpetual excitement.”

At the eleventh hour Margaret found a reason to regret her departure: Charles King Newcomb, the eighteen-year-old son of one of the “coterie of Hanna Mores,” “a new young man, very interesting, a character of monastic beauty, a religious love for what is best in Nature and books.”

Charles had just returned from a year at the Protestant Episcopal Theological Seminary in Virginia; he was one of those men “rushing back into mysticism”—possibly even Catholicism—whom she had envisioned in her Coliseum Club talk. His spiritual quest intrigued her, as did the opportunity to influence his development—attractions that would draw her to other younger men in coming years. They walked in the evening moonlight in the woods above the city; he wrote her letters “full of affection and faith,” which she had little time to answer, “for all the little imps of care are round me.” Still she urged him, “Write to me, if you will; it gives pleasure.”

But “a new young man” was not enough to lure Margaret from the close proximity of enigmatic, “unhelpful, wise” Waldo Emerson. In December, after a tearful parting with her “row” of pupils, who presented her with an “elegantly bound”

set of Shakespeare, Margaret was off to the “vestal solitudes” of Groton.

“I do not wish to teach again at all,” she declared. She knew she might not have her wish, but she expected to devote at least a year to “my own inventions” before attempting once more to effect “my dreams and hopes as to the education of women,” if necessary. And: “What hostile or friendly star may not take the ascendant before that time?” For now, making her escape from Providence mattered most of all. She had felt there “always in a false position,” teaching when she would rather be writing, gabbling when she wished to converse.

Margaret had advised her students that a woman must strive to discover and attain “everything she might be.” “Who would be a goody that could be a genius?” she had demanded of Waldo Emerson. It was time for Margaret to answer her own question.

• IV •

CONCORD, BOSTON, JAMAICA PLAIN

Caroline Sturgis

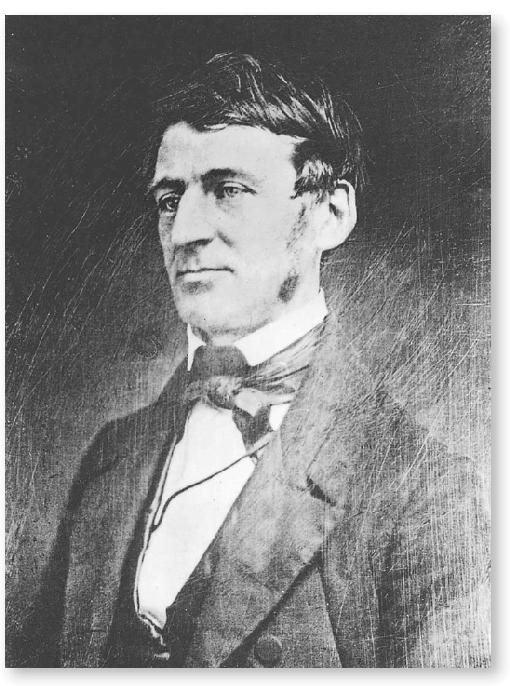

Samuel Gray Ward

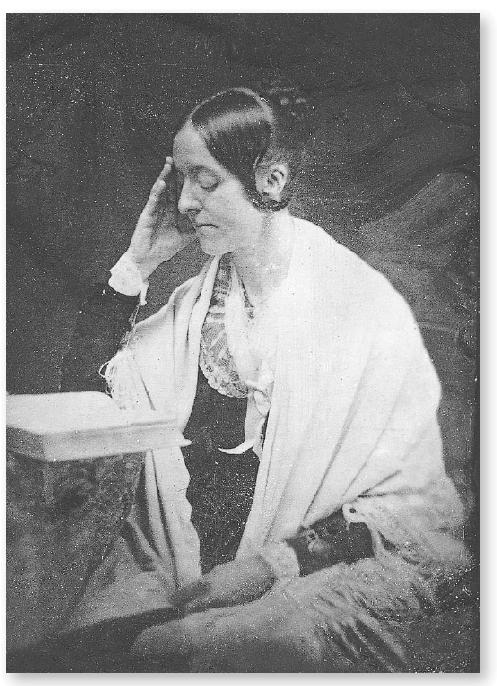

Anna Barker Ward

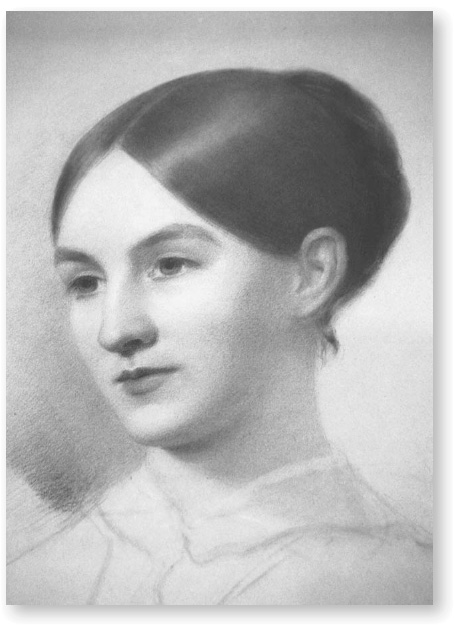

Margaret Fuller

Ralph Waldo Emerson

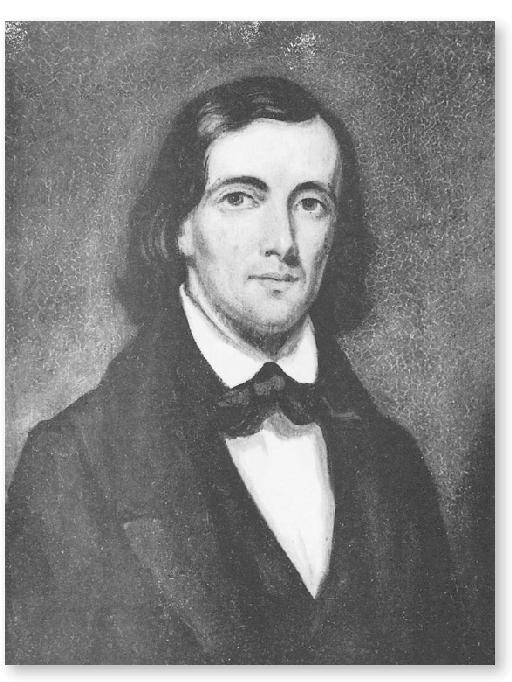

Ellery Channing

Ellen Kilshaw Fuller

10

“What were we born to do?”

M

ARGARET RARELY THOUGHT THE POETRY SHE WROTE

—to express private longings or, at times, rhapsodic joy—was publishable. The elegy to Waldo Emerson’s brother Charles, published in a Boston newspaper in 1836, had a specific occasion and also a purpose: to communicate her sympathy to the grieving older writer in the weeks before their first meeting. But when James Clarke printed several verses that she’d sent him by letter in his

Western Messenger,

without asking her permission, she was outraged: “all the value of this utterance is destroyed by a hasty or indiscriminate publicity,” she complained. She felt “profaned” to have these “overflowings of a personal experience”—they were lines she’d written to comfort herself in the months of crisis after Timothy Fuller’s death—offered up to strangers’ eyes. There was nothing “universal” in them that might “appeal to the common heart of man,” as the works of a true poetic genius like Byron or Goethe would.

Fortunately, only her mother had recognized the lines as her work; James at least had the sense not to print Margaret’s name.

Yet when John Sullivan Dwight asked if she’d like to attach her name to the two verse translations he’d chosen for his anthology

Select Minor Poems of Goethe and Schiller,

Margaret was happy to be identified, even though she considered her renderings of Goethe’s lyrics into English “pitiful” and “clumsy” compared to Dwight’s.

But what name would she choose? Three years before, her “Lines” on the death of Charles Chauncy Emerson had appeared with an ambiguous “F” as signature.

Now, at Margaret’s request, “Eagles and Doves” and “To a Golden Heart, Worn Round His Neck” were listed on the contents page of

Select Minor Poems

as the work of “S. M. Fuller”—concealing, for those who didn’t know her, the fact that she was the only female among the contributors to the volume, and signaling to those who

did

that she was one of the boys. Margaret had not graduated from Harvard with them, but here at last she joined the triumvirate of young, disaffected Unitarian ministers, James Clarke, Henry Hedge, and her old friend William Henry Channing, their names printed in full alongside a handful of New England literary men: G. W. (George Wallis) Haven, N. L. (Nathaniel Langdon) Frothingham, and C. P. (Christopher Pearse) Cranch. Here too appeared George Bancroft, who’d earned his doctorate at Göttingen and whose screed against Brutus had prompted Margaret’s first anonymous publication five years earlier, before her father’s death. Now she was Bancroft’s equal in the pages of a landmark volume, the first translation from German in George Ripley’s ambitious series Specimens of Foreign Standard Literature.