Margaret Fuller (2 page)

Authors: Megan Marshall

But while I never gave up the aim of representing Margaret Fuller’s many accomplishments, as I read more of her letters, journals, and works in print, I began to recognize the personal in the political. Margaret Fuller’s critique of marriage was formulated during a period of tussling with the unhappily married Ralph Waldo Emerson over the nature of their emotional involvement; her pronouncements on the emerging power of single women evolved from her own struggle with the role; even her brave stand for the Roman Republic could not be separated from her love affair with one particular Roman republican. It was not true, as she had written of Mary Wollstonecraft, that Margaret Fuller was “a woman whose existence better proved the need of some new interpretation of woman’s rights, than anything she wrote.”

Her writing was eloquent, assured, and uncannily prescient. But her writing also confirmed my hunch. Margaret Fuller’s published books were hybrids of personal observation, extracts from letters and diaries, confessional poetry; her private journals were filled with cultural commentary and reportage on public events. Margaret did not experience her life as divided into public and private; rather, she sought “fulness of being.”

She maintained important correspondences with many of the significant thinkers and politicians of her day—from Emerson to Harriet Martineau to the Polish poet and revolutionary Adam Mickiewicz—but she valued the letters she received above all for the “history of feeling” they contained.

She, like so many of her comrades, both male and female, valued feeling as an inspiration to action in both the private and public spheres. I would write the full story—operatic in its emotional pitch, global in its dimensions.

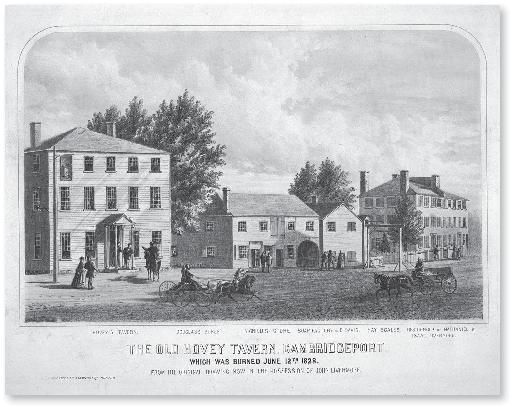

Margaret Fuller’s mind and life were so exceptional that it can be easy to miss the ways in which she was emblematic of her time, an embodiment of her era’s “go-ahead” spirit. Her parents grew up in country towns in Massachusetts, their families eking out a tenuous subsistence in the early years of the republic; both were drawn to city life, and they met by chance, crossing in opposite directions on the new West Bridge, the first to connect Cambridge and Boston. Their life together through Margaret’s childhood was urban, following a national trend: the population of the United States tripled during Margaret’s lifetime, transforming American cities. The advent of railroads and a massive influx of immigrants from overseas stimulated urban growth.

By the late 1830s and ’40s, when Margaret was a young single woman living in Providence, Boston, and Cambridge, New England had become the first region in the country with a shortage of men. The overcrowded job market and economic volatility that drove her lawyer father back to farming and her younger brothers to seek employment in the South and West created this imbalance, leaving one third of Boston’s female population unmarried. Little wonder that Margaret toyed for a while with the notion that only an unmarried woman could “represent the female world.”

Her argument was theoretical: American wives belonged by law to their husbands and could not act independently. Yet she also spoke for a surging population of women, many of them single, who sought usefulness outside the home and who readily joined the political life of the nation by advocating causes from temperance to abolition long before they gained the right to vote.

Despite her allegiance to women’s rights and her important alliances with reform-minded women, Margaret Fuller was never a joiner. She took to heart the example of the French novelist George Sand, whom she met in Paris, a woman who effectively articulated her ideas through both conversation and published writing and who chose an independent path in life. She was impressed by the way Sand “takes rank in society like a man, for the weight of her thoughts.”

In a time when “self-reliance” was the watchword—one she helped to coin and circulate—Margaret had, by her own account, a “mind that insisted on utterance.”

She too insisted that her ideas be valued as highly as those of the brilliant men who were her comrades. She refused to be pigeonholed as a woman writer or trivialized as sentimental, and her interests were as far-ranging as the country itself, where, as she wrote in a farewell column for the

Tribune

when she sailed for Europe, “life rushes wide and free.”

In England, France, and Italy, Margaret found, as the stay-at-home Ralph Waldo Emerson predicted, even more members of her “expansive fellowship”:

radical thinkers, revolutionaries, and artists of the new age. Yet even in this journey to the Old World she was marking out a new American life—a route traced in the future by the likes of Henry James, Edith Wharton, Mary Cassatt, John Reed, Ernest Hemingway, and countless other seekers of inspiration and new theaters of action abroad.

Nathaniel Hawthorne, a friend of Margaret Fuller’s in Concord who followed her path to the Continent several years after her death, undertook an experiment in fictional form when he put aside writing stories in favor of longer narratives.

He preferred to call his books “Romances,” not novels. “When a writer calls his work a Romance,” Hawthorne explained in his preface to

The House of the Seven Gables,

“he wishes to claim a certain latitude, both as to its fashion and material, which he would not have felt himself entitled to assume had he professed to be writing a Novel.” The novelist, in Hawthorne’s terms, aims to achieve “a very minute fidelity” to experience, whereas the author of a romance may “bring out or mellow the lights and deepen and enrich the shadows of the picture” while still maintaining strict allegiance to “the truth of the human heart.”

My book is not a work of fiction, but I have kept in mind Hawthorne’s notion of the “Romance” as a guiding principle in my factual narrative. Or, to borrow from Margaret Fuller herself, “we propose some liberating measures.”

I have brought out lights and deepened shadows, intensifying focus, for example, on Margaret’s friendships in a circle of young “lovers” who were drawn to the flame of her intelligence during the years of her closest friendship with Emerson, and on her experience as a mother separated from her infant son during wartime.

My account lingers on such points to render the complexity of her lived experience and to make full use of the rich documentation of these key episodes. At other times the narrative takes a more rapid pace to chart the swift trajectory of this “ardent and onward-looking spirit” whose life spanned only forty years.

Margaret Fuller maintained that all human beings are capable of great accomplishment, that “genius” would be “common as light, if men trusted their higher selves.”

Still, she was always mindful of her own extraordinary capabilities. “From a very early age I have felt that I was not born to the common womanly lot,” Margaret wrote to a friend as her thirtieth birthday approached.

This awareness was a source of frequent inner turmoil as she strove to realize her talents in an era unfriendly to openly ambitious women. Yet she achieved almost inconceivable success, with remarkable poise. After talking her way into the library at Harvard to complete research on her first book, Margaret did not allow the gawking undergraduates, who had never before seen a woman at work in their midst, to break her concentration. A few years later she occupied a desk in another all-male setting, the newsroom at Horace Greeley’s

New-York Tribune,

where she turned out editorials and cultural commentary aimed at shaping the opinions of her fifty thousand readers on subjects from literature and music to Negro voting rights and prison reform.

In Rome, offering her views in a

Tribune

column on the U.S. government’s need to appoint an ambassador to the new Roman Republic, Margaret conjectured, “Another century, and I might ask to be made Ambassador myself.” But in this case, she was forced to admit, “woman’s day has not come yet.”

In the twenty-first century, woman’s day may almost have arrived. American women vote and hold high office as elected representatives, judges, diplomats, even secretaries of state, if not as president. Yet Margaret Fuller’s journalistic descendants still risk their lives, not just because they work in dangerous places, but because they are female, objects of scorn and worse, in many parts of the world, for daring to serve in the public arena. What was it like to be such a woman—the only such woman, the first female war correspondent—a half-century after America’s own revolution?

I have written Margaret Fuller’s story from the inside, using the most direct evidence—her words, and those of her family and friends, recorded in the moment, preserved in archives, and in many cases carefully annotated and published by scholars of the period. A close reading of this now well-established manuscript record yielded many perceptions that I hope will strike readers familiar with Margaret Fuller’s life as fresh and true. I have also relied on a number of previously unknown documents that emerged during my years of research on the Peabody sisters and later as I tracked my current subject in archives across the country: two newly discovered letters by Margaret Fuller, a record in Mary Peabody’s hand of Margaret Fuller’s first series of Conversations for women held in Boston in 1839, the Peabody sisters’ correspondence during the months following the wreck of the

Elizabeth,

and a letter written by Ralph Waldo Emerson to the Collector of the Port of New York, itemizing the trunks and valuables lost in the fatal storm.

“The scrolls of the past burn my fingers,” Margaret Fuller wrote to her great friend Ralph Waldo Emerson concerning some particularly painful letters the two had exchanged; “they have not yet passed into literature.”

So impassioned are her words, they burn our fingers yet, two centuries later.

Margaret Fuller: A New American Life

is my attempt to transport those letters into literature, to give her magnificent life “a little space,” as she asked from Emerson, so that “the sympathetic hues would show again before the fire, renovated and lively.”

As for Margaret herself—if she reached a heaven, we may hope it is like the one she once imagined, “empowering me to incessant acts of vigorous beauty.”

• I •

YOUTH

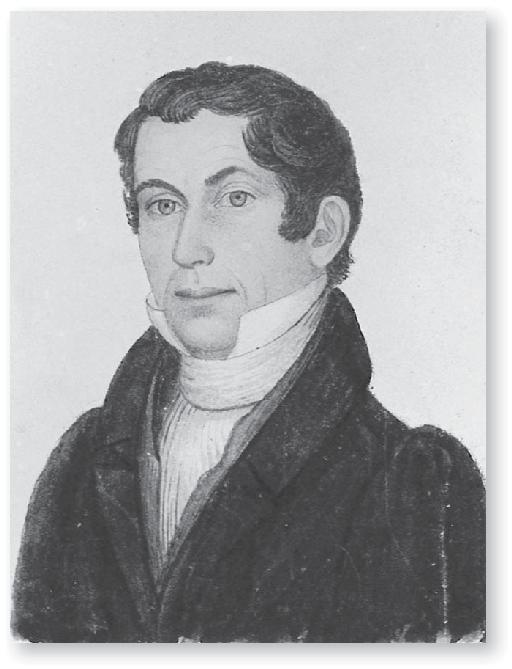

Timothy Fuller, portrait by Rufus Porter

Margarett Crane Fuller, daguerreotype, c. 1840s