Map of a Nation (51 page)

Authors: Rachel Hewitt

To glean the fullest picture of Ireland’s toponymy, O’Donovan struck up

discussions

with Irish citizens both young and old, literate and illiterate, from working-class labourers to aristocratic landowners, Catholics and Protestants. As an Irish-speaking Catholic himself who carried a bishop’s testimonial to his ‘useful, laudable and patriotic pursuit’, he received a friendly welcome from many residents who had given the British military engineers the cold shoulder. Between 1834 and 1842 John O’Donovan became ‘a kind of one-man local history department’. In his letters, he offered animated verbal caricatures of his interlocutors, and did not hold back when he came across an enemy. After a disagreeable meeting with a Protestant clergyman in Rathfriland, County Down, O’Donovan recorded: ‘I was never so disgusted with any little

Cur, whelp

, or

pup

in all my life. His petty aristocratic assumptions and

ungentlemanly

remarks had a very disagreeable effect upon my sensitive nerves.’ O’Donovan was entranced by puns and obscenities and reflected to Larcom that ‘in the present artificial state of society it is curious to observe that one word is filthy, while another that expresses the same identical idea is honor[able], as a[rs]e, backside, bottom, etc.’ His irreverence often clashed with Larcom’s moralism. The staid and precise military engineer was not amused by his young employee’s digressions, and he complained: ‘O’Donovan really writes in a way that vexes me. It is rather too much to suffer him.’ Larcom declared himself disgusted by the extent to which O’Donovan’s

letters

were ‘defaced (or disgraced) by scurrility’ and ‘ribaldry’, and – with his tongue planted firmly in his cheek – O’Donovan duly promised to his superior that he would, in future, make his letters ‘very serious, cold, and un-Irish’.

It should not be imagined that O’Donovan took his work anything but seriously, however. He was convinced that toponymic research was every bit as rigorous a science as surveying, and stated himself to be ‘as sceptical an enquirer as any in existence’ and ‘exceeding (excessive) in love with

truth

to the prejudice of all national feelings’. George Petrie, the Topographical Branch’s director, loved the way in which O’Donovan’s work exhibited an ‘evident approach to the character of

scientific

proof

’. O’Donovan’s obsession

with the scientific accuracy of his linguistic work arguably levelled the

playing

field on which the Topographical Branch fought for attention with the ostentatiously scientific Trigonometrical Survey, and also demanded that space be made on the British map for

Irish

needs.

O’Donovan’s emphasis on the utter seriousness of his researches

counteracted

a prevalent notion that the history of the Irish language was ‘a region of fancy and fable’, in Petrie’s words. In the mid eighteenth century, Irish literature had suffered from a notorious literary hoax when the Scottish writer James MacPherson claimed to have discovered manuscript fragments of the works of a third-century poet, ‘Ossian, the son of Fingal’, from which he published ‘authentic’ translations. MacPherson asserted that his texts offered ‘convincing proof’ that stories of the legendary Irish figure of Fionn mac Cumhaill were merely versions of a much older Scottish epic about the character Fingal. Many readers were instantly sceptical, mainly because MacPherson could not, or would not, produce his original manuscripts. The poems were eventually written off by most as a fraud that had been composed by MacPherson himself, but in O’Donovan’s eyes they had already done a great deal of damage. ‘The poems of Ossian have

bewildered

the minds of the peasantry in Ireland and of the literati in Scotland,’ he declared, feeling that they had undermined the status of Irish Gaelic

literature

. O’Donovan also translated ancient Irish poems and he distinguished his own endeavour from MacPherson’s by insisting on publishing the

original

texts alongside his English versions to give them ‘incontestible authority’.

In England and Wales, Thomas Colby had taken a utilitarian stance

regarding

toponymy and recommended that the versions of each place name that were spoken most widely should be selected for the map. But in Ireland, John O’Donovan fought for more attention to be given to place names’ history. He persuaded Larcom that the Ordnance Survey should adopt ‘that one among the modern names most consistent with the ancient orthography, not noticing the ancient name merely to interest the antiquary, but approaching as near to it as was practicable without Fancy’. O’Donovan wanted the Ordnance Survey’s maps of Ireland to display the forms of contemporary place names that drew closest to the oldest Irish version that the Topographical Branch’s researches had unearthed, thus making room on the map for ‘all the rhymes

and rags of history’. The names’ Irish spellings were to be anglicised on the map, and he urged that these translations should be based more on the

original

Irish names’ pronunciations than on attempted transliterations of their meanings. (In respect to house names and private estates, however, the Ordnance Survey continued to defer to the desires of the owner.)

O’Donovan’s emphasis on history can be interpreted politically. He hinted that the modern Irish landscape was a tragic Babel in which ‘the people do not agree upon the names of [their villages]; the name by which the whole of one mountain is known to one, being that by which a part of it only is known to another’. In O’Donovan’s view, the principal cause of such

linguistic

confusion was the introduction of English settlers into Ireland, and that nation’s history of plantation meant that Ireland had developed a ‘forked tongue’, a bilingual habit that had ‘mangled’ its old Irish names. He described some of these distortions in disgust: ‘To comply with the general custom of sticking

town

as a tail to as many of these names as possible, the ancient name of Queen

Taillteann

, the daughter of

Mamore

was changed to Telltown, as if it were impossible to

tell

what

town

it anciently was (the name of)!’ He worried that the Ordnance Survey’s military engineers risked perpetuating this history by insensitively anglicising Ireland’s place names on their maps. O’Donovan ridiculed the way in which, in a townland near Tobermore, County Londonderry, called Mainister Uí Fhloinn (Monaster O’Lynn, or O’Lynn’s Monastery), the surveyor had jotted down the highly anglocentric misspelling ‘

Money Sterling!

’ in his name book. O’Donovan must have been horrified when the misnomer of ‘Moneysterlin’ actually found its way onto the map.

It seems that O’Donovan thought of himself as a linguistic archaeologist, excavating the ‘pure’ old Irish names from generations of layers of confusion and change. In a poem, a ‘wild rhapsody’ that he sent to Larcom in 1834, O’Donovan described how he ‘trace[d] his course along the darkened tract’ of history, ‘Facts shedding light before him as he goes’. He was wary of over-reliance on the spoken evidence given by living Irish residents, and favoured old printed texts and ancient manuscripts. O’Donovan was Adam in the Garden of Eden, doling out names to Ireland’s lush pastures, rolling hills and effervescent rills. And his Eden was predominantly

Irish

. In the

Ordnance Survey, O’Donovan appears to have seen an opportunity to

resurrect

the face of the nation as it had appeared before the arrival of the English and the ensuing traumatic history of plantation.

At the Topographical Branch, O’Donovan worked alongside a man called James Clarence Mangan, who was employed as a copyist and scribe and who also wrote poetry. Mangan cut a strange figure among his colleagues. As a child, he had contracted a severe influenza that had badly affected his eyesight and compelled him to don green goggles as protection against the sun. These looked extraordinary against his vivid yellow hair (possibly a wig), and ‘skin as pale and taut as parchment’. As a poet, he occasionally adopted the pseudonym ‘The Man in the Cloak’ and lived up to his name by wrapping himself in a huge blue cape, hunched beneath a large pointed hat ‘of fantastic shape’. A friend commented that Mangan ‘looked like the spectre of some German romance rather than a living creature’. He was an unhappy man, who was said to be oppressed by ‘the animal spirits and hopefulness of vigorous young men’ – despite the fact that Mangan was only in his early thirties when he worked for the Topographical Branch – and he was seen to ‘fle[e] from the admiration and sympathy of a stranger as others do from reproach or insult’. He drank heavily and O’Donovan described scornfully how his colleague was so well known to Dublin’s public houses that their landlords provided this ‘

poète maudit

’ with ‘pens and ink –

gratis

’. Indeed, O’Donovan related how ‘one short poem of his exhibits seven different inks, and

seven different

varieties of hands, good or bad, according to the number of glasses of whiskey he had taken at the time of making the copy’.

O’Donovan and Mangan clearly did not see eye to eye, in professional or personal matters. They lived close to one another, and O’Donovan described to a friend ‘the mad poet who is my next-door neighbour’. ‘[Mangan] says that I am his enemy,’ the linguist recounted half-mockingly, ‘[and that I] watch him through the thickness of the wall which divides our houses. He threatens in consequence to shoot me. One of us must leave.’ In turn,

contravening

Larcom’s impression of O’Donovan as an inappropriately jocular man, Mangan found his colleague to be ‘severe, coldly-judging, and testing ethics by the science of mathematics’. Most crucially, the two men possessed very different views regarding the method and function of translation. Mangan

often professed that ‘the merit of fidelity’ is ‘of a very questionable kind in translations’, and in 1826 he composed a poem mocking ‘bad Etymology and sad Orthography’. For Mangan, the past was irretrievable and he described in a poem how ‘Dates, arithmetical tack, and all chronological cumber,/ Shall have been hurried, swept, hurled, as obsolete masses of lumber,/ Into the gulph of gloom, from whence there is no reappearing.’ Changes in place names and in language were inevitable consequences of the inexorable march of time, and Mangan saw the task of the translator as that of a parent, fathering new and different offspring from old texts, rather than a linguistic archaeologist excavating the past. He had no compunction about translating from texts composed in languages he did not speak, and it was even rumoured that he did not speak Irish.

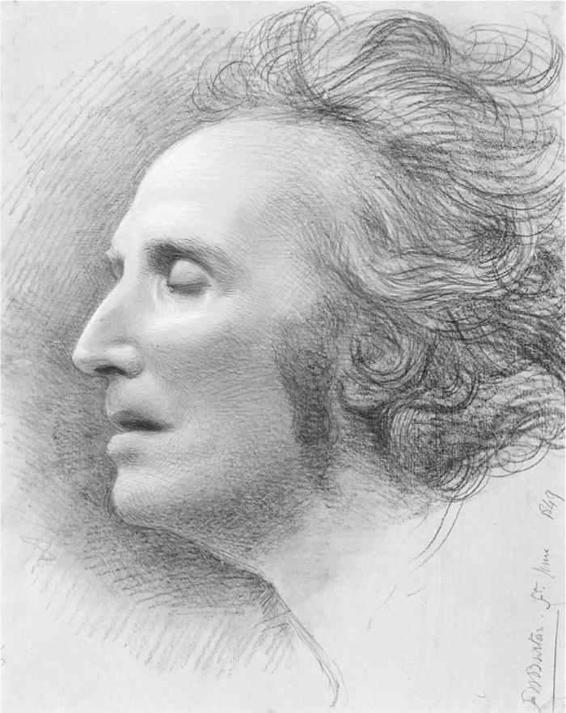

37. James Clarence Mangan by Frederick William Burton, made after Mangan’s death in the Meath Hospital, Dublin, in 1849.

As a copyist, Mangan seems to have had little say over the place names that were adopted on the Irish Ordnance Survey maps, and he and O’Donovan clashed most visibly in matters of poetry in translation. In 1852

Mangan published an English translation of a poem by the

sixteenth-century

Irish poet Aengus O’Daly, which was edited by his antagonistic colleague. O’Donovan surrounded what Mangan designated as his ‘Versified Paraphrase, or imitation, of Aengus O’Daly’s Satires’ with critical footnotes, commenting variously that ‘this is incorrect’, ‘Mangan totally mistook the meaning of this quatrain’, ‘the translator is here very wide of the meaning’, and ‘the poet is not very happy here’. The last footnote unwittingly hit the mark: Mangan certainly wasn’t very happy. It seems that his distaste for O’Donovan’s mission to resurrect old Ireland’s place names made

collaborations

with the linguist painful and his employment on the Topographical Branch an unpleasant experience. Some years after its closure, Mangan described mournfully how his work there had turned him into a ruin of his former self: ‘The few broken columns and solitary arches which form the present ruins of what was once Palmyra, present not a fainter or more imperfect picture of that great city as it flourished in the days of its youth and glory than I, as I am now, of what I was before I entered on the career to which I was introduced by my first acquaintance with that lone house [i.e. Teepetrie] in 1831.’