Map of a Nation (49 page)

Authors: Rachel Hewitt

William Rowan Hamilton’s contact with Colby and Larcom indicates that their time in Ireland was sociable and intellectually stimulating. But it was not just Anglo-Irish scientists and mathematicians with whom the two map-makers mingled. In the late 1820s, Colby and Larcom started to entertain grand plans for the Irish maps that would bring them into contact with a bevy of geologists, statisticians, anthropologists, linguists, poets and, crucially, orthographers.

C

HAPTER

E

LEVEN

P

HYSICAL CHALLENGES

, perilous peaks and endurance exercises excited Thomas Colby, but his assistant was more cerebral. In the summer of 1828, with the Trigonometrical and Interior Surveys of Ireland well launched, Thomas Aiskew Larcom decided to brush up his knowledge of the Irish language. On applying to the Irish Society for tutelage, the

surveyor

was recommended a Gaelic Irish scholar from south Kilkenny, who introduced himself as John O’Donovan (or Seán Ó Donnabháin). A

pleasant

-looking 22-year-old, with a wide-eyed open expression and ‘peasant garb’, O’Donovan had had a peripatetic upbringing. He had been first educated in a hedge school, part of a rural pedagogical system in which students were taught by educated members of the community, usually in a barn or house. There he had learned to read English and Irish, and had been taught in arithmetic and geography. Later O’Donovan attended a private school in Waterford and a Latin school in Dublin, and lessons with a relative gave him facility in Latin and various European languages. But O’Donovan’s real intellectual awakening had occurred after his father’s death, when he had spent two years with his uncle Patrick, described by his nephew as ‘the living repertory of the traditions of the counties of Kilkenny, Carlow, and Wexford’. It was ‘from him I first caught that love for ancient Irish and Anglo-Irish history and traditions

which have since afforded [me] so much amusement,’ O’Donovan fondly recalled.

This revelation of Ireland’s ancient history and language changed O’Donovan’s life, and it would alter the Irish Ordnance Survey’s course too. Although O’Donovan had flirted with a career in the Catholic priesthood, he rejected the idea in order to follow his linguistic infatuations. During a period in Dublin in the mid 1820s, O’Donovan had met a host of scholars prominent in Irish studies, an area in which intellectual interest was rapidly burgeoning. This friendly, eager young man made the acquaintance of James Scurry, author of a paper on ‘Grammars, Glossaries, Vocabularies and Dictionaries in the Irish Language’ that was read before the Royal Irish Academy in 1826. And Scurry introduced O’Donovan to James Hardiman, Dublin’s Commissioner of Public Records. Hardiman was a committed researcher in the history of the Irish language and its literature, and he encouraged interest in Ireland’s linguistic history as a way of bolstering the nation’s

self-confidence

. ‘After ages of neglect and decay, the ancient literature of Ireland seems destined to emerge from obscurity,’ he predicted. ‘Those memorials which have hitherto lain so long unexplored, now appear to awaken the

attention

of the learned and the curiosity of the public; and thus, the literary remains of a people once so distinguished in the annals of learning, may be rescued from the oblivion to which they have been so undeservedly consigned.’

Shortly after their first meeting in Dublin in 1828, Hardiman offered John O’Donovan a job as a copyist of Irish manuscripts and legal

documents

, which he accepted. And in that same year, Larcom also approached the scholar with an offer of employment as a tutor in Irish, and O’Donovan again happily agreed. For the next couple of years, the two men – one a calm, upright, meticulous military officer, the other an animated and rather irreverent linguist – met three times a week over breakfast, while Larcom developed a proficiency in the language of the nation that he was mapping. But O’Donovan was fearsomely overworked, and after a time he had to put an end to the early-morning tuition.

L

ARCOM’S INTEREST

IN

learning Irish was fuelled by ambitious plans that he and Colby entertained for the survey of Ireland. Throughout its mapping of England and Wales, the Ordnance Survey had repeatedly been seduced into diversions from the main priority of the completion of the First Series of one-inch maps, and it was no different in Ireland. There Colby and Larcom both came round to the opinion that ‘geography is a noble and practical science only when associated with the history, the commerce, and a knowledge of the productions of a country; and the topographical

delineation

of a county would be comparatively useless without the information which may lead to, and suggest the proper development of its resources’. In Britain, Colby had been content to produce maps and measurements alone, but he had mostly left their wider applications to the statisticians,

industrialists

, landowners, agricultural reformers, guidebook writers, travellers, civil servants and others who consumed their data. In Ireland he took a different tack, and Colby and Larcom together formulated a plan of making what the latter called ‘a full face portrait of the land’. The two map-makers

recognised

that their chart was a valuable opportunity to glean information about Ireland’s history, culture, economy, geology, religious practices, languages, antiquities, and industrial and agricultural potential. They resolved to make a

survey

of Ireland in the true sense of the word: a bountiful overview of the nation, with an eye to its improvement. As this suggests, Colby had started to feel more engaged with the country. This may have had something to do with the fact that in 1828 he married an Irishwoman called Elizabeth Hesther Boyd, a daughter of the Treasurer of Londonderry. Little is known about Elizabeth, but it seems that his marriage helped to reconcile Colby to his prolonged residence in Ireland.

From the start, the Ordnance Survey’s Irish endeavours were more

wide-ranging

than they had ever been in Britain. Alongside the creation of a Trigonometrical Survey and a topographical map, Colby was also focused on mapping the borders of Ireland’s townlands, to assist with the recalculation of the county cess tax. A separate Boundary Commission was formed in 1825 to work alongside the Ordnance Survey under the supervision of a man called Richard Griffith, who ascertained the rough shape of Ireland’s townlands from landowners, estate maps, clergymen and various officials. To map them in

detail, Griffith then recruited local residents to give the Ordnance Survey’s map-makers a tour of the boundaries, for 2s a day. If these impromptu guides were uninformative, or the boundaries indistinct (as was often the case over bogs or mountainous ground), the surveyors tended to simply concoct the course of the borders themselves. The precise area of each townland was needed for the calculation of the tax and at first this was measured on the ground itself by the surveyors, but once the maps had been engraved it became easier to work out these areas on paper.

The Ordnance Survey and the Boundary Commission did not always see eye to eye. Colby and Griffith cordially disliked one another, and each team regularly accused the other of incompetence. When Griffith was given the task of assigning a monetary value to each townland, based on its soil,

buildings

, relief, cultivation and population, he realised that the maps that were being produced by the Ordnance Survey in the late 1820s were not up to the job. Tiny errors, such as misplaced buildings, undefined bogs or other

omissions

, hindered Griffith’s efforts and he duly instructed Colby to rectify these deficiencies. But the map-makers had much to criticise too. Some accused Griffith of distorting or even ignoring the measurements they had made of the boundaries. After showing proof copies of the charts to a local

community

in County Londonderry, one surveyor was forced to report back to Larcom: ‘the people deny that many denominations set down as townlands on our maps are townlands’. ‘I am inclined to believe,’ he continued, ‘that Mr Griffeth [

sic

] frequently divided parishes into townlands, more from his own fancy than from the authority of the people.’ The situation did not improve with time. Two years later, the same map-maker wrote despairingly: ‘I cannot get the people to agree with Griffith’s names or Subdivisions. They say that he got Gentlemens’ Stewards, who were often not long in the Country, to point out the boundaries, and that these frequently by ignorance, and not seldom by intention, set him astray.’ After the Irish Ordnance Survey was over, the

Morning Chronicle

reflected the same opinion: ‘Mr Griffith is an excellent and able engineer, but he knows no more of farming than engineers generally do; that is, nothing at all. We are well acquainted with many of the districts that he sets down as cultivable wastes, and we say that practical farmers hold a perfectly opposite opinion about them.’

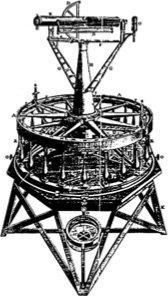

Colby and Larcom entertained still greater ambitions for their map than the creation of trigonometrical, topographical and boundary surveys. As part of their conviction that the mapping project should chart Ireland’s historical face and industrial potential, they also wanted to look

below

the earth’s surface. In fact, the idea of establishing a permanent Geological Survey to work in

parallel

with the Ordnance Survey had been mooted since the early years of the nineteenth century, when Interior Surveyors had conducted rudimentary

geological

researches to assist with their hill-drawing. And when William Mudge had measured a meridian arc across England, and his results had been

unexpected

, the geologist John Playfair had pointed out that Mudge’s observations may have been distorted by the attraction of the instruments’ pendulums to various land masses. ‘It would have been of great importance to have added to [the Trigonometrical Survey] a mineralogical survey,’ Playfair tutted, ‘as the results of the latter might have thrown some light on the anomalies of the former.’ The Ordnance Survey had duly remedied this complaint, and between 1814 and 1821 a man named John McCulloch, who was appointed chemist to the Board of Ordnance, turned his attention to geology. McCulloch spent every summer analysing the rocks around the Ordnance Survey’s

triangulation

stations, to ascertain if their levels of attraction might pose a threat to the precision of the map-makers’ instruments. An awestruck onlooker

commented

to McCulloch: ‘no person but a man of iron like yourself could have gone over such an extent of rugged country with so much minute accuracy’.

Colby considered the Irish Ordnance Survey as the ideal opportunity to build on these geological beginnings. He issued detailed instructions to his surveyors, and the finished maps of Ireland duly exhibit a plethora of

limestone

quarries and gravel pits. Colby wanted them to comprise ‘the most minute and accurate geological survey ever published’. Nevertheless, it was back in England that an official Geological Survey was set up in this period. McCulloch had remarked on the ease with which such an endeavour could be attached to the Ordnance Survey, and in the spring of 1835 the

Master-

General

of the Ordnance and its Board formed a committee, which included the influential geologists Charles Lyell, William Buckland and Adam Sedgwick, to debate the matter. The result was that ‘a grant was obtained from the Treasury to defray the additional expense which will be

incurred in colouring geologically the Ordnance county maps’. But before this date a ‘gentleman geologist’ and owner of a slave plantation in Jamaica, Henry de la Beche, had taken a keen, if amateur, interest in the Ordnance Survey. This man, described by an acquaintance as ‘a regular fun-engine’, enjoyed colouring in the Ordnance Survey’s charts of Devon according to their geological strata. When the income from his Jamaican plantation

completely

failed in the early 1830s, de la Beche applied to the government for a grant to complete his geological survey and was duly made the Ordnance Survey’s official geologist and director of an embryonic geological museum. De la Beche’s subsequent career went from strength to strength. He

published

Researches in Theoretical Geology

in 1834, an official

Report on the Geology of

Cornwall, Devon and West Somerset

four years later, was knighted in 1842, elected President of the Geological Society in 1847, and proudly oversaw the opening of the Museum of Practical Geology on London’s Jermyn Street and the foundation of a School of Mines and of Science applied to the Arts. Henry de la Beche remained the bespectacled face of the Ordnance Survey’s Geological Survey until 1845.