Making It: Radical Home Ec for a Post-Consumer World (22 page)

Read Making It: Radical Home Ec for a Post-Consumer World Online

Authors: Kelly Coyne,Erik Knutzen

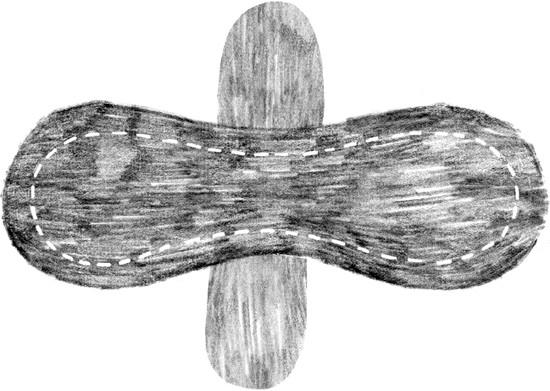

POSITION WINGS

If using wings, position the two wings between the backing and top material, equidistant between the two ends of the pad. They’ll be sewn into place when you sew the rest of the pad. Lay them so one wing crosses on top of the other

B

and so their raw edges line up with the raw edges of the pad fabric. (Imagine the pad has its arms folded, rather than outstretched.) This way, when the pad is turned, the wings will be in the right place. You could attach them later by sewing them to the back side of the pad once it’s turned, but that doesn’t look as neat.

SEW THE PAD

Stitch together the layers, following the contour of the pad, allowing a ¼-inch seam allowance all around. Leave a 2- to 3-inch opening at one end.

Turn the pad inside out through the opening: Reach between the top material and the backing material and pull from there. After turning, the core fabric should end up hidden, you should see only the material you intended for the front and the back, and the wings should be in place.

A SHORT CUT

Stitching and turning create a clean-edged pad. If you don’t mind a frayed edge, you can assemble all of the pieces in their final order and topstitch them together using the zigzag setting on your machine. Just stitch all around the edges. If you have a serger, the edges could be serged all the way around.

Close the opening by tucking the raw edges under to match the seam you’ve already made. Pin the edges into place or iron them flat, then hand-sew the hole closed or topstitch with the machine.

TOPSTITCH THE PAD

Topstitch the entire pad. This keeps the layers from puffing or slipping around, and the resulting channels can help direct menstrual flow. You can stitch it any way you like, really. If your top fabric has a pattern on it, you can stitch along the pattern to give the pad a fancy quilted effect. Or you could be more utilitarian and sew a simple 5-inch line straight up the middle. Or trace all around the edges of the pad, placing the needle ½ to 3/4 inch in from the outer edge.

ADD THE SNAPS TO THE WINGS

Add sew-on snaps to the wings, if using. The snap halves should be placed to meet at the center of the pad. Fold the wings against the pad and put a little mark on both to mark the center point. One half of the snap is the ball and the other half the socket. It doesn’t matter which half goes on what side, but they do have to be sewn on opposite faces of the wings so they’ll meet when the wings are folded under the pad. In other words, when the pad is flat and the wings are outstretched, one part of the snap faces up and the other faces down.

Both halves of the sewn-on snaps will be ringed with four or more small holes on the edge. Using a needle and thread, hand-stitch the snaps to the wings by looping the needle in and out of the first pair of holes five or six times. Then move on to the next hole. The more anchoring stitches, the stronger the snap.

The wings are very forgiving regarding placement of the snaps. Don’t worry too much about precise centering or if the snaps shift around a little when you sew them.

Finished Pad

USING YOUR PADS

WASHING

The best way to prevent stains from setting is to soak pads in cold water, preferably from the moment you take them off, though this is not always possible. Leave the pads soaking until you have a chance to wash them. Designate a bucket or covered container for this purpose. We’ve heard of watering cans being used for soaking. This is a great idea, because bloody water is an excellent fertilizer. Plants love it. Sure, the idea may seem a little strange at first, but if you think about it, it’s nice to know all that blood is going to good use.

If it will be several days before you launder, switch out the soaking water for fresh every other day so funky smells don’t develop. Just pour off the water onto a grateful plant, then add fresh water to the bucket. On wash day, drain the water and toss the soggy pads straight into the machine.

WHEN YOU’RE OUT AND ABOUT

Carry a clean pad in a little bag, like a pencil case. Swap it for a used pad when you need to. Don’t worry about carrying a used pad around with you. We promise, packs of dogs won’t follow you down the street.

No one will ever know.

Take the used pad home and drop it in the soaking bucket.

HOW MANY PADS DO YOU NEED?

Depends on you. Keep count of how many disposable pads you go through each month and which types you use. That will be a good approximation of what to make, though you might find that you use fewer cloth pads. They hold a lot of blood and don’t crumple and twist with wear, like disposables do.

You’ll probably add to your collection over time and experiment with designs. For instance, you might decide you want an extralong pad with a flaring back for overnight use or a set of petite panty liners made out of some fabulous fabric.

In general, panty liners are about 6 to 8 inches long, regular pads are in the 9- to 10-inch range, maxipads are around 11 inches, and overnight/postpartum pads can be as long as 13 inches.

If you’re just not a pad kind of gal but are interested in reuseable protection, investigate menstrual cups, like the DivaCup or the Keeper, or try sea sponge tampons. Menstrual cups last for years, sponges for 4 to 6 months. Both are more economical and environmentally friendly than regular tampons.

Section Four

Season to Season

The projects in this section are things we do a few times a year. Some of them follow the course of the seasons, like preparing a garden bed for planting, while others yield results that we use for months, like handcrafted soap or a stockpile of home brew. Here, ambition and rewards are directly correlated.

42>

Making Soap the Easy Way

You might have heard that it takes a long time to make soap. Or if you’ve ever looked at a typical soap-making book, you might have been put off by the long list of exotic vegetable oils, expensive fragrance blends, and other daunting ingredients involved in the recipes. What if we told you that you could make soap in your countertop blender in 15 minutes, and that all you needed was a bottle of olive oil and a can of drain opener?

It really is that simple. The resulting soap is a rich, gentle castile soap suitable for both body and hair. This is kitchen alchemy at its best.

BLENDER SOAP

Most soap-crafting books assume that you want to make a lot of soap at once. Standard recipes make 20 bars or more at a time, so they have to be made in a big pot and stirred laboriously with a spoon or a stick blender. One batch of our blender soap yields about a pound of soap, which is about 3 cups in its liquid form, which yields four or five large bars. To us, this is an advantage, because it allows for experimentation and minimizes material losses if something goes wrong.

The major objection to making soap in a blender is the risk of a blender disaster occurring. Say the lid pops off during the blending process, or the base comes loose, and hot, caustic soap spills everywhere. This is a real risk, but one that can be counterbalanced by taking the proper precautions. Any type of soap making must be performed with all due caution, and that caution can be applied to blender soaps as easily as any other method. To us, the advantages of making soap in a blender—the speed and flexibility—outweigh the risks. These instructions have to be long, because there are lots of warnings and “explanifying,” but once you have the steps down, you’ll find you can make a batch of blender soap faster than a batch of cookies.

REGARDING LYE

Soap is created through a chemical process called saponification, in which acid (in the form of fats and oils) reacts with a strong base, an alkali of a metallic salt. The alkali used to make bar soap is sodium hydroxide. The common term for sodium hydroxide (or similar alkalis) mixed with water is

lye.

“Lye soap” has become a misleading synonym for harsh soap, but the truth is that all soap is made with lye. Saponification is a chemical transformation. Once the process is complete, there is neither fat nor lye present in a bar of soap—soap is the product of their reaction. The relative harshness or mildness of any soap is determined by both the quality of the fats used and the proportion of fat to lye.

Pure sodium hydroxide is sold in hardware stores as drain opener. This is the easiest way for a home crafter to find it. Read the label. It should say 100 percent sodium hydroxide. Drano is not sodium hydroxide. If you have trouble finding sodium hydroxide at the hardware store, order it from soaping or chemical supply companies.

REGARDING TEMPERATURES

There are two basic types of soap making: hot process, where the soap is made over heat, and cold process, where the lye and the oils are brought into a certain temperature range and combined off the heat. Blender soap is a variant of the cold-process method. In the cold-process method, saponification is guaranteed to occur if the oils and the lye are mixed when each is in the temperature range of 90° to 110°F. The temperatures of the two don’t have to match; they just have to fall somewhere in that range.

Measuring the temperature of the oils and lye is considered a critical step in traditional soap making. However, the blender soap enthusiasts claim that in their method, the oils and lye do not have to be mixed at any particular temperature, that it all works, no matter what. The crazy thing about this is that they seem to be right. We’ve made batch after batch of soap this way without taking temperature readings, and they’ve all come out fine. This might be because of the small quantity of materials or the violence of the mixing. If, however, for some reason your blender soap doesn’t set up, use the temperature guidelines above in your next batch, and success will be guaranteed. If you decide to make a

large

batch of soap in a pot, definitely use those temperature guidelines.

SOAP-MAKING EQUIPMENT

Use the following tools and equipment for all our soap recipes.

COUNTERTOP BLENDER WITH A GLASS MIXING JAR.

Why glass? When sodium hydroxide is combined with water, a chemical reaction occurs that heats the mixture upward of 180°F. Lye is also quite caustic. Under such extreme conditions, plastic containers, unless heatproof, can become dangerously flexible. We believe it is safer all around to use glass containers. We use our everyday glass blender and Pyrex mixing cups to make soap and have found that the ingredients do not damage them or leave residue behind. Some people choose to have a complete set of equipment used solely for making soap. The call is up to you.

DIGITAL KITCHEN SCALE.

Precise measurements are important.

HEATPROOF GLASS CONTAINER

to mix the water and lye, like a Pyrex measuring cup.

SPOON FOR MIXING THE LYE.

Lye is hard on spoons, so you may wish to use a designated spoon for this purpose. Don’t use an aluminum spoon, because it will react with the lye. Plastic, rubber, and wood are all good choices, though wood will degrade. We use disposable chopsticks.

INSTANT-READ COOKING THERMOMETER.

This is optional for blender soap but imperative for other kinds of soap making.

KITCHEN GLOVES.

EYE PROTECTION,

like shop goggles (or ski goggles or a diving mask or a motorcycle helmet . . .).

MOLD FOR THE SOAP.

For your first outing, we recommend an empty quart milk carton. It’s the easiest solution and makes nice square bars. Wash out the carton and open the top completely to facilitate pouring. When the soap sets, you just peel away the carton. Don’t use any sort of foil-lined carton, because the lining might react with the soap. Alternatively, you could use any container with a 3-cup volume, like a small box or baking tin, lined with plastic wrap or cut-up plastic bags. Leave enough extra plastic dangling over the sides to serve as handles for unmolding the soap later. The disadvantage of plastic is that it leaves impressions of wrinkles in the soap unless you are preternaturally skillful at laying it out. If you get into soaping, you can buy specialized soap molds from craft stores or soaping suppliers or make your own wooden breakaway molds.

Genuine Castile Soap

PREPARATION:

15 min

WAITING:

4 weeks

Castile soap has become a catchall term for any soap made with vegetable oil. The original castile soap came from Spain and was made with pure olive oil. It’s hard to find pure olive oil soap anymore. This is a shame, because pure olive oil soap is exceptionally mild and rich, if a little more slippery and less lathering than modern soap. We like it a lot and use it for both body and hair. It’s also easy to make on a whim, because all you need is lye and olive oil.

Don’t be intimidated by the length of these instructions. There’s a lot of detail, but the actual process of mixing up the soap takes only a few minutes. Make sure to read the entire project first—maybe read it twice, just to be safe. After you make this recipe once or twice, you’ll be a pro.

YOU’LL NEED

- 2 ounces sodium hydroxide

- 6 ounces distilled, filtered, or bottled drinking water

- 16 ounces olive oil (Not extra-virgin; lower grades work better for soap. Be sure to buy pure olive oil, though, not a “light” mix of olive oil and other vegetable oils.)

- 1 teaspoon essential oil for scent (optional)

SAFETY WARNING

Lye (sodium hydroxide) is not only hot when mixed with water, it’s also caustic. Any splashes will burn your skin and damage your eyes. Put on your goggles and gloves before you start working. You should also wear long sleeves, long pants, and closed-toe shoes. Secure infants or pets somewhere for a few minutes, so they’re not underfoot.

If you spill liquid lye on your skin, rush to the sink and flush your skin with cold water for several minutes, then wash with soap. If you spill dry lye crystals on yourself, remove them carefully. Even perspiration can activate the crystals, so use a hand broom or something similar to brush them off. If you feel any itching, which is the precursor to burning, flush with cold water as above. If lye gets in your eyes, flush with cold water and go straight to the hospital. Never apply vinegar to a lye burn.

PUTTING IT TOGETHER

STEP 1: MEASURING THE LYE AND WATER

Place a small bowl on a digital kitchen scale, turn on the scale, and set the weight to zero. Add the sodium hydroxide crystals until the scale reads exactly 2 ounces.

Fill a heatproof glass container with 6 ounces water. You can measure the water on the scale as you did with the sodium hydroxide or use a liquid measuring cup.

STEP 2: MIXING THE LYE AND WATER

Perform this step either outdoors or near an open window. Sprinkle the lye crystals

into

the water. Do not pour water

over

the lye crystals, because it might create a volcanic effect. Stir until the crystals are dissolved. The reaction will create both heat and odor, so don’t hold the container in your hands.

The mixture will be cloudy. Let it sit until it turns clear, about 5 minutes.

STEP 3: MIXING THE OIL AND LYE

While the lye is settling, weigh out the 16 ounces of oil on the scale the same way you did the sodium hydroxide.

Do a “preflight” check of your blender. Make sure the bottom ring is threaded correctly and secured tightly. Pour the oil into the blender. If you’re using essential oil, measure it and set it to one side. Make sure the soap mold is ready to go.

As soon as the lye mixture turns clear, add it slowly and carefully to the oil in the blender. Be sure to wear gloves and goggles as you do this.

Put the lid on the blender. Cover the lid with a kitchen towel as an extra safety precaution. Holding the lid down with one hand, set the blender to the lowest possible speed. Start mixing.

After 10 seconds, stop mixing. Let the contents settle, then carefully remove the lid. The liquid in the blender will already be opaque. From here forward, you will alternate short bursts of blending, no more than 30 seconds at a time, with pauses to check progress. Watch for signs that the soap has reached the stage called “trace,” which is the point of no return in saponification. Recognizing trace is the trickiest part of soap making. The liquid will turn creamy first, then thicken. Once it starts to thicken, it will turn solid quickly. You need to pour it into the mold before it becomes too thick to handle easily. The total time this takes varies with different sorts of soaps. For this olive oil soap, it will probably take about 5 minutes of blending.

Here’s how you watch for trace: Monitor progress by dipping a spoon into the blender and dribbling a few drops off the spoon on the surface of the soap.

USING TEMPERATURE TO DETERMINE TRACE

If you have an instant-read thermometer, you can verify the visual clues that your soap is about to reach the trace stage. Take a baseline reading of the temperature of the oil and lye when they are first mixed, then measure the temperature each time you stop to check progress. Saponification releases heat, so the temperature of the mix will rise when saponification occurs. When the temperature has increased by 2° or 3°F, the mixture is ready to mold. Any higher than that, and the soap is already setting up.

At the early stages, the surface will not hold any memory of these drizzles or any traces of the spoon’s path as you stir. However, you will notice that it is getting thicker, turning from an opaque but thin liquid into something more the consistency of eggnog. When it gets to this stage, pay very close attention when you test. When you see even the

slightest

sign of the surface displaying a memory, it’s reached “trace” and is ready to be molded. Add essential oil, if desired, at this point and blend it for a couple of more seconds. Don’t lollygag, because time is short.

If the swirls don’t reincorporate at all but sit on the surface, as they would in pudding, the soap is setting up and you need to rush to get it into a mold.

STEP 4: MOLDING THE SOAP

Pour the soap into the mold. If the soap has just reached trace, it should be pourable. If it’s too thick to pour, ladle it into the mold with a spoon and tap the mold on the counter to remove air pockets. Then smooth the surface of the soap with the back of a spoon. The surface might be lumpy, but that’s only a cosmetic flaw.