Mad Enchantment: Claude Monet and the Painting of the Water Lilies (6 page)

Read Mad Enchantment: Claude Monet and the Painting of the Water Lilies Online

Authors: Ross King

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Architects, #History, #General, #Modern (Late 19th Century to 1945), #Photographers, #Art, #Artists

Permission for the pond was quickly granted, thanks to Monet having some strings to pull with local journalists and politicians. He was good friends with the mayor of Giverny, Albert Collignon, another

horzin

. Collignon was a distinguished writer and intellectual who had founded a journal,

La Vie littéraire

, and published impor tant works on Stendhal and Diderot.

36

He was sympathetic to Monet’s aspirations, and by the end of the year the painter had been allowed to divert the river and, by means of a system of sluices and grilles, create a small pond over a narrow stretch of which—probably inspired by his Hokusai woodcuts—he had an elegant Japanese bridge constructed.

The first water lilies arrived in 1894, courtesy of Joseph Bory Latour-Marliac, a skilled and enterprising botanist with a nursery near Bordeaux. By cross-breeding white water lilies from northern climes with more vivid tropical varieties from the Gulf of Mexico, Latour-Marliac had created the first viable colored water lilies in Europe. He showed these exotic cultivars, with their palette of yellows, blues, and pinks, at the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1889, in a garden at the Trocadéro, across the Seine from the Eiffel Tower, likewise unveiled to the world in 1889. The sight of these gorgeous new hybrids had inspired Monet. He wished to create a garden, he wrote, to “please the eyes”; but he also wanted, from that first glimpse at the Trocadéro, to provide himself with what he called “motifs to paint.”

37

Monet’s original order from Latour-Marliac included six water lilies—two pink and four yellow—along with various other aquatic plants, such as water chestnut and bog cotton.

38

He also ordered four Egyptian lotuses, which, despite Latour-Marliac’s assurances that they were capable of surviving in Normandy, quickly perished. However, the water lilies thrived, and Monet subsequently placed orders for red varieties. In the winter of 1895 he set up his easel beside the water and began to paint his pond for the first time. A year later he was visited by a journalist,

Maurice Guillemot, who enthused over the “strangely unsettling” blossoms floating among glassy reflections. Monet confided to Guillemot that he hoped to decorate a circular room with these green and mauve blossoms and reflections.

39

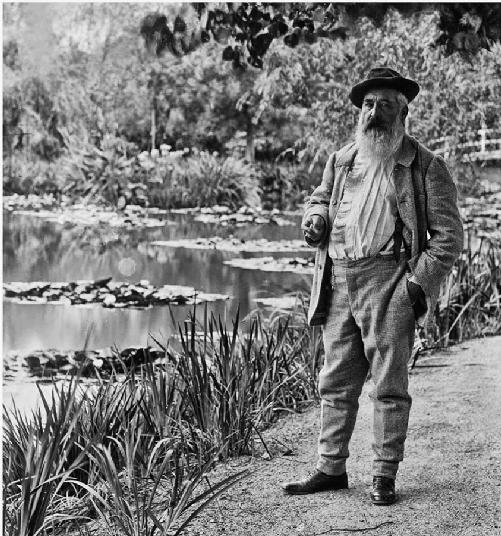

Monet beside his newly expanded water lily pond in 1905, around the time he began painting his “landscapes of water.”

Nothing came of this plan, and Monet’s paintings of his pond went into storage. He set about expanding the water garden a few years later, buying an adjacent parcel of land that, once more earth was moved, further sluices added, and the Ru once again diverted in its bed, effectively tripled the size of the pond. Meanwhile he constructed four new bridges, while to the existing Japanese bridge he added a trellis for wisteria. Bamboo, rhododendrons, and Japanese apple and cherry trees joined the willows artfully disposing themselves along the margins of the pond.

The running costs were, of course, fabulously expensive. Greenhouses were constructed, including one dedicated to the water lilies, complete with its own heating system. The team of gardeners toiled

through the seasons. In 1907, when passing automobiles showered his water lilies with dust, Monet paid for the chemin du Roy to be tarmacked rather than—as he had been doing—instructing his gardeners to give the lily pads a daily dunking. Altogether he spent some 40,000 francs per year on his gardens. Monet’s lavish means meant, however, that he could easily meet these extravagant costs, since his bank accounts, chock-full from the sales of his works, meant he was earning some 40,000 francs in annual interest payments alone.

40

EARLIER IN HIS

career, Monet had roved widely around France, palette and paintbrush in hand. In 1886 he worked along the windswept cliffs of Belle-Île-en-Mer, ten miles off the coast of Brittany. In 1888 he went with Renoir to Antibes, in the South of France, returning with gorgeous portraits of the Côte d’Azur. The following year he spent three months at Fresselines, painting beside the steep gorge of the river Creuse, 220 miles south of Paris.

After buying Le Pressoir in 1890, Monet still made the occasional painting expedition: to Norway to visit a stepson, to the Normandy coast, to London three times between 1899 and 1901 and a trip to Venice with Alice in 1908, where the two of them, looking every inch the tourists, posed for photographs among the pigeons in the Piazza San Marco. However, the vast majority of Monet’s paintings after 1890 were done within a mile or two of his house. In the 1890s he began devoting himself to local subjects such as the wheat stacks in the nearby meadow, the poplar trees beside the river Epte, and scenes of the Seine downstream at Vernon and upstream at Port-Villez. He painted the ancient church of Notre-Dame perched above the river at Vernon, and in the summer of 1896 he began rising at three thirty in the morning and paddling onto the Seine in a flat-bottomed boat so he could capture the dawn mists.

Local these scenes might have been, but the Monet scholar Paul Hayes Tucker has shown that they possessed powerful national resonances as evocations of an essential Frenchness. Monet’s paintings of wheat stacks, for instance, were images of the bountiful and enduring landscape, what Tucker calls a “rural France that is wholesome and

fecund, reassuring and continuous.”

41

Likewise the poplars, which were a crop planted for both firewood and the building industry. Indeed, the poplars Monet painted beside the Epte were due to be chopped down before he finished his canvases, forcing him to purchase the entire crop (which, unsentimentally, he sold to a timber merchant once his works were done). The poplar was, moreover, the “tree of liberty” in France, adopted as such, Tucker notes, because its name came from

populus

, which meant both “people” and “popular.”

42

The Gothic cathedral of Rouen was even more obviously a symbol of France, the representative of an architectural style, born on the Île-de-France, that spread across Western Europe during the Middle Ages. As a critic wrote in December 1899, with these paintings Monet “expressed everything that forms the soul of our race.”

43

There was a certain irony in the fact that this catering to a yearning for visions of rural France was done by a man whose own rustic neighbors scorned him as an intruder unsympathetic to their age-old country ways. Indeed, Monet was not unlike the exotic water lilies whose existence depended on the diversion of the natural course of a river essential to rural life: he, too, was an exotic import whose presence in Giverny was not in keeping with, or conducive to, the traditional ways of life that he made his fortune from depicting on canvas.

Despite these canvases making him wealthy and famous, by the end of the century Monet abruptly abandoned these patriotic and quintessentially French scenes of the countryside near Giverny. Instead, his subjects became even more circumscribed as he turned almost obsessively, and at the expense of all else, to his garden. As his friend Gustave Geffroy wrote: “The powerful landscapist who so strongly expressed the greatness of the sea, cliffs, rocks, ancient trees, rivers and cities, took pleasure in a sweet and charming simplicity, in this delightful corner of a garden, this tiny pond where blossoms some mysterious petal.”

44

The turning point, as Tucker points out, had been 1898, a date that coincided with the climax of the Dreyfus Affair, the political scandal and miscarriage of justice in which the wrongful conviction for espionage of Alfred Dreyfus revealed an ugly anti-Semitism at the highest levels

of French society.

45

Monet’s friends Clemenceau and Émile Zola took leading and, indeed, heroic roles in the affair, with the former publishing the latter’s famous article “J’Accuse”—a master class in speaking truth to power—in his newspaper

L’Aurore

. “Bravo and bravo again,” Monet wrote to Zola, who was promptly convicted of libel and forced to flee across the channel to England.

46

No more patriotic scenes of the French countryside, no more expressions of the soul of the French race, issued forth from Monet’s brush. How could a Dreyfusard such as Monet celebrate or even represent France after the nation’s glory had been, as Zola wrote, “threatened by the most shameful and most indelible of stains”?

47

Indeed, following Zola’s trial, he stopped painting altogether for eighteen months.

“Il faut cultiver notre jardin,”

wrote Voltaire at the end of

Candide

. Monet proceeded to do precisely that: he cultivated his garden, whose Japanese bridge, rose alley, weeping willows, and water lilies—none of which was evocative of the French countryside or the soul of the French race—would provide, over the next quarter of a century, material for some three hundred paintings. This narrowing of geographical range to the boundaries of his own property did not mean a curtailing of his artistic vision. Far from it, as astute critics quickly realized. “In this simplicity,” wrote Geffroy, “is found everything the eye can see and surmise, an infinity of shapes and shades, the complex life of things.”

48

If William Blake saw the world in a grain of sand, Monet could glimpse, in the mirrored surface of his lily pond, the dazzling variety and abundance of nature.

MONET’S PAINTINGS OF

his garden eventually became even more critically and commercially successful than his canvases of wheat stacks, poplars, and cathedrals. In 1909 he unveiled forty-eight of them at an exhibition in Paris entitled

Les Nymphéas: Séries de paysages d’eau par Claude Monet

(

The Water Lilies: Series of Waterscapes by Claude Monet

). With rapid and lucrative sales, it was the most resoundingly triumphant exhibition of his career. A critic in the

Gazette des Beaux-Arts

declared: “For as long as mankind has been around, and for as long as artists have painted, no one has ever painted better than this.” Another critic crowned Monet as “the greatest painter

we possess today.”

49

His work was compared to Michelangelo’s frescoes in the Sistine Chapel and to Beethoven’s last quartets.

50

Monet’s renown as France’s greatest painter—not to mention France’s most famous gardener—was complete. But after such success, of course, came the deluge of sorrow: the deaths of Alice and Jean, the trouble with his eyes, the forced retirement of his brushes. Monet must have wondered, too, about his artistic fate. In 1905 the influential critic Louis Vauxcelles wrote that Monet reminded him of Ernest Meissonier.

51

He was referring to Monet’s physical appearance: his long white beard and robust frame. But Monet’s tremendous wealth and success, together with his imposing country house and his obstreperous temperament, bore uncomfortable comparison with the arrogance and extravagance of France’s mightiest artistic titan in the years of Monet’s youth—the Meissonier whose paintings drew huge crowds and changed hands for vast sums, who spent a fortune on his splendid mansion in Poissy, who used his vast property as a stage set for his paintings, and who was celebrated as the most renowned artist of his age. But following his death in 1891, Meissonier had vanished into almost unrelieved obscurity. “Many people who had great reputations,” Meissonier had once observed with an anxious eye on the prospects for his own posterity, “are nothing but burst balloons now.”

52

Monet could have been forgiven for worrying that his balloon would likewise burst and that, like Meissonier, he would pay for the Olympian success of his lifetime with disdain and anonymity after his death.

The warning signs were already flashing. The legacies of Monet and his fellow Impressionists were still in doubt. In 1912, Vauxcelles declared: “It is generally agreed that Impressionism has passed into history. Younger artists, while paying their respects, must seek other things.”

53

The movement had indeed passed into history. The Impressionists had exhibited together for the last time in 1886, more than a quarter of a century earlier. The participants had passed, or were passing, from the scene. Édouard Manet had died in 1883, the very week that Monet moved to Giverny. Berthe Morisot followed in 1895, Alfred Sisley in 1899, Camille Pissarro in 1903, and Paul Cézanne in 1906. The surviving

members were largely inactive due to the infirmities of age. The seventy-three-year-old Renoir, arthritic and wheelchair-bound, had retired to the South of France, where he presented a “frightful spectacle” to visitors.

54

Edgar Degas, approaching eighty, was in a worse condition: a bitter and misanthropic recluse. “Death is all I think of,” he announced to the few souls who could stand his company.

55

Mary Cassatt described him as a “mere wreck.”

56

She, like him, was virtually blind and, also like him, had stopped painting altogether—a fate that it appeared Monet was about to share.