Mad Enchantment: Claude Monet and the Painting of the Water Lilies (4 page)

Read Mad Enchantment: Claude Monet and the Painting of the Water Lilies Online

Authors: Ross King

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Architects, #History, #General, #Modern (Late 19th Century to 1945), #Photographers, #Art, #Artists

Clemenceau called Monet by an assortment of nicknames: “old lunatic,” “poor old crustacean” and “frightful old hedgehog.”

59

He had come by his own nickname, the Tiger, quite honestly. As a newspaper reported the previous January, he was “a man before whom the whole world trembles.”

60

His political enemies liked to refer to him by the full title that he never actually used: Georges Clemenceau de la Clemencière. He had been born in the Vendée, along France’s Atlantic coast, and raised

in the massive Château de l’Aubraie, a moated manor house with a ring of walls and four towers. This grim castle and the ornate title could be traced back to a certain Jehan Clemenceau who, sometime after 1500, was ennobled by King Louis XII for having served as the “beloved and trusty bookseller” of the bishop of Luçon.

61

Later generations of the family loved books but were, as far as both church and state were concerned, much less beloved and trusty. Georges’s father, Benjamin, was a rabid republican and anti-Catholic. “The natural state of my father was indignation,” Georges once observed.

62

Master of all he surveyed, squire of many acres of farmland tilled by peasants, Benjamin seethed with revolutionary fervor in his gloomy castle, which he decorated with portraits of Robespierre and other heroes of 1789. He was an outspoken opponent of the Emperor Napoleon III, who once had him arrested on suspicion of participating in an assassination plot. “I will avenge you,” vowed the seventeen-year-old Georges as his father was marched away to prison.

63

Much of the rest of Clemenceau’s life had been spent exacting revenge on his and his father’s enemies. “I feel very sorry for those people who want to make friends with everyone,” he once said. “Life is a combat.”

64

He had indeed made many enemies and experienced much combat, sometimes literally: he had fought a total of twenty-two duels with swords and pistols. A journalist once claimed there were only three things to fear about Clemenceau: his tongue, his pen, and his sword.

65

He was a master of the witty put-down. About the young journalist Georges Mandel he quipped: “Mandel has no ideas, but he will defend them until death.”

66

Clemenceau studied medicine in Paris in the early 1860s, writing a dissertation on the soon-to-be-disproved theory of spontaneous generation. His true vocation, however, was radical politics. For many years he was leader of the Radical Party, whose members saw themselves as latter-day Jacobins fighting to preserve the French Republic established in 1789. Like his father, he was a fierce enemy of the Church and an ardent republican, and for several months in 1862 he had likewise been a political prisoner thanks to having distributed pamphlets critical of the emperor. In 1865 the emperor’s crackdown on dissidents drove him into voluntary exile in the United States, where for several years

he supported himself by teaching French, fencing, and horseback riding at the Catharine Aiken School for girls in Stamford, Connecticut. Here he found a wife, Mary, the daughter of a New Hampshire dentist. The marriage would not be a happy one, not least because of Clemenceau’s numerous dalliances with beautiful actresses. “What a tragedy that she ever married me,” he later reflected in a rare moment of regret.

67

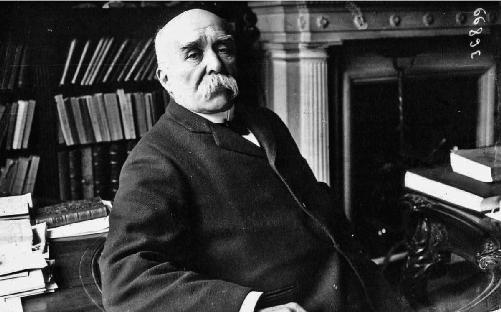

Georges Clemenceau

Clemenceau had returned to France in the summer of 1869 to work as a country doctor in the Vendée. His political career began in earnest with the fall of Napoleon III during the Franco-Prussian War. In September 1870 an old friend of his father, Étienne Arago, who had just become mayor of Paris, appointed him mayor of the working-class hilltop suburb of Montmartre.

WE ARE CHILDREN OF THE REVOLUTION

, Clemenceau’s posters on the steep streets proudly declared.

68

He doubled as a doctor, opening a clinic through which filed, he sorrowfully observed, a “procession of human miseries” from the slums.

69

After six years, he got himself elected as Montmartre’s representative in the Chamber of Deputies, where his reputation for bringing down

governments (thirteen collapsed in the 1880s alone) brought him the nickname

tombeur de ministères

(toppler of ministries). He had little respect for his fellow politicians, later telling Rudyard Kipling that he obtained his eminence in politics not through any excellent qualities of his own “but through the inferiority of my colleagues.”

70

Active in journalism since his student days, in 1880 he launched a radical newspaper,

La Justice

, whose first issue declared his intention to “destroy the old dogmas.”

71

However, the newspaper folded and his political career imploded in the wake of the liquidation in 1892 of the Panama Canal Company amid charges of swindling and bribery in which he was implicated. That same year his marriage likewise collapsed. “I have nothing, nothing, nothing,” he wrote in a fleeting moment of despair.

72

But scandal, disgrace, poverty, and divorce were no match for Clemenceau. He returned to prominence through his support in a series of articles in his new newspaper,

L’Aurore

, for Alfred Dreyfus, the Jewish artillery officer unjustly convicted of spying for the Germans. After a decade in the political wilderness he was elected to the Senate in 1902, then appointed minister of the interior in 1906. Later that year, at the age of sixty-five, he became prime minister, serving until the summer of 1909. He pushed through social reforms, including holidays for workers and the creation of a ministry of labor. But the campaigning journalist who had been a champion of the poor and the suffering took a brutal approach with dissenters who threatened revolution. His ruthless suppression of striking miners and winegrowers earned him yet another nickname,

briseur de grèves

(strikebreaker) and even Clemenceau le Tueur (Clemenceau the Murderer). And it was in these years that he was given the sobriquet by which all France came to know him—the Tiger—a comment on the terror that he inspired in virtually everyone. As a friend wrote, “People were unfailingly petrified of him.”

73

Yet Clemenceau also had immense charm and culture. The wife of a British statesman found him “swifter in thought, wittier in talk, more unexpected in what he said, than anyone I ever knew...No one was ever such fun as he was. We hung upon his every word.”

74

If he was anathema to most politicians, who hated and feared him, he was a great friend to

artists and writers. Clemenceau patiently sat for two portraits by Édouard Manet, reporting that he had “great times” talking with the infamous painter.

75

He had artistic pretensions of his own, writing novels and short stories (one collection was illustrated by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec). In 1901 his play

Le Voile de Bonheur

was performed at the Théâtre de la Renaissance in Paris. He was also a connoisseur, amassing a huge collection of Japanese art and artifacts: swords, statuettes, incense boxes, tea bowls, woodblock prints by Utamaro and Hiroshige, all of which he lovingly crammed into his small apartment across the Seine from the Eiffel Tower. Japanese art was yet another passion that he shared with Monet, whose house displayed his collection of 231 woodblock prints.

Most of all, Clemenceau was a connoisseur and admirer of Monet’s works. The series of paintings of Rouen Cathedral, painted in 1892 and 1893 and exhibited in Paris in 1895, compelled him to write a long and ecstatic review in

La Justice

. The subject of these canvases was an ironic one to appeal to a notorious priest-gobbler and republican like Clemenceau: the façade of the ancient cathedral in which during the Middle Ages the dukes of Normandy were crowned. But Clemenceau was intoxicated. “It haunts me,” he wrote on the front page of the newspaper. “I must talk about it.” He regarded Monet—who possessed, he said, “the perfect eye”—as the herald of nothing less than a revolution in human vision, “a new way of looking, feeling and expressing.” Who could doubt, looking at Monet’s canvases, “that today the eye sees in another way than before?” He ended his article by imploring France’s president, Félix Faure, to buy all twenty of the paintings in the show for the nation in order to mark a “moment in the history of mankind, a revolution without gunshots.”

76

Faure declined to purchase any works, but the idea of having a cycle of Monet’s paintings serve as a national monument became a mounting obsession among Clemenceau and his artistic friends.

*

As Clemenceau and Monet transformed from enfants terribles to grand old men, becoming two of the most famous men in France, the affection between them grew. There was a steady stream of letters, lunches together in Paris, and regular visits by Clemenceau to Giverny. Clemenceau’s dedication to Monet became even greater after the death of Alice. He provided endless encouragement, issuing invitations to Bernouville, escorting Monet around gardens, and persuading him to take holidays. Most of all, he urged him to keep painting. “Remember the old Rembrandt in the Louvre,” he wrote two months after Alice’s death. “He clings to his palette, determined to hold out until the end through terrible adversities.”

77

*

Clemenceau would exact revenge on Faure, an anti-Dreyfusard, with a famous pun. After Faure died in 1899 while being fellated by his mistress, Marguerite Steinheil, Clemenceau quipped:

“Il voulait être César, il ne fut que Pompée.”

The literal meaning is: “He wanted to be Caesar, but only ended up as Pompey.” However, the phrase is a

double entendre

, since the French verb

pomper

(to pump) was slang for oral sex.

CHAPTER TWO

DU CÔTÉ DE CHEZ MONET

“AS SOON AS

you push on the small door on the main street of Giverny,” wrote one of Monet’s best friends and most frequent visitors, the writer Gustave Geffroy, “you can believe...that you have stepped into paradise.”

1

On that April day in 1914 the door to this paradise—a “slightly worm-eaten door,” as one guest noted

2

—would have been opened by Blanche Hoschedé-Monet, whom Monet affectionately called “my daughter.”

3

Blanche was, in fact, his stepdaughter but also, by virtue of her marriage to his son Jean, his daughter-in-law. Plump, blue-eyed, blond, and cheerful, the forty-eight-year-old Blanche was the vision of her mother. She was also the only one of Monet’s children or stepchildren with artistic interests or aspirations. As a young woman she had been his faithful assistant, helping to carry his easel and canvases into the fields for him. She had also painted side by side with him, setting up her easel next to his and hewing closely to his Impressionist style. Occasionally she managed to exhibit or sell her work, although she suffered in comparison to her stepfather, “a master,” as a critic pointed out in a review of her paintings at the 1906 Salon des Indépendants, “whom it is dangerous to imitate.”

4

Jean’s illness had brought her back to Giverny, where she attended to her husband’s needs and then, following Jean’s death, to those of her stepfather. Clemenceau called her the “Blue Angel”: a reference to her blue eyes and sweet, generous nature. Her younger brother Jean-Pierre Hoschedé—another faithful and beloved stepchild—noted that after Jean’s death she was “at Monet’s side, always and everywhere.”

5