Lost in the Cosmos: The Last Self-Help Book (14 page)

Read Lost in the Cosmos: The Last Self-Help Book Online

Authors: Walker Percy

Tags: #Humor, #Essays, #Semiotics

The community of art is not the elect community of science but the community of the artist and all who share his predicament and who can understand his signs.

The impoverishment? It comes from the transience of the salvation of art, both for the maker of the sign (the artist) and for the receiver of the sign.

The self in its predicament is exhilarated in both the making and the receiving of a sign—for a while.

After a while, both the artist and the self which receives the sign are back in the same fix or worse—because both have had a taste of transcendence and community.

If poets often commit suicide, it is not because their poems are bad but because they are good. Whoever heard of a bad poet committing suicide? The reader is only a little better off. The exhilaration of a good poem lasts twenty minutes, an hour at most.

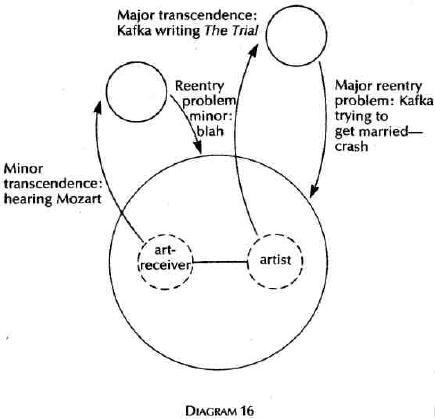

Unlike the scientist, the artist has reentry problems that are frequent and catastrophic.

In fact, a catalogue of the spectacular reentries and flameouts of the artist is nothing other than a pathology of the self in the twentieth century, much as the fits and frenzies of Saint Vitus’s Dance were signs of the ills of an earlier age.

What account, then, can a semiotic give of the paradoxical impoverishments and enrichments of the self in the present age?

Why do people often feel bad in good environments and good in bad environments? Why did Mother Teresa think that affluent Westerners often seemed poorer than the Calcutta poor, the poorest of the poor?

The paradox comes to pass because the impoverishments and enrichments of a

self in

a

world

are not necessarily the same as the impoverishments and enrichments of an

organism

in an

environment.

The organism is needy or not needy accordingly as needs are satisfied or not satisfied by its environment.

The self in a world is rich or poor accordingly as it succeeds in identifying its otherwise unspeakable self, e.g., mythically, by identifying itself with a world-sign, such as a totem; religiously, by identifying itself as a creature of God.

But totemism doesn’t work in a scientific age because no one believes, no matter how hard he tries, that he can “become” a tiger or a parakeet. Cf. the depression of a Princeton tiger or Yale bulldog, one hour after the game.

In a post-religious age, the only recourses of the self are self as transcendent and self as immanent.

The impoverishment of the immanent self derives from a perceived loss of sovereignty to “them,” the transcending scientists and experts of society. As a consequence, the self sees its only recourse as an endless round of work, diversion, and consumption of goods and services. Failing this and having some inkling of its plight, it sees no way out because it has come to see itself as an organism in an environment and so can’t understand why it feels so bad in the best of all possible environments—say, a good family and a good home in a good neighborhood in East Orange on a fine Wednesday afternoon—and so finds itself secretly relishing bad news, assassinations, plane crashes, and the misfortunes of neighbors, and even comes secretly to hope for catastrophe, earthquake, hurricane, wars, apocalypse—anything to break out of the iron grip of immanence.

Enrichment in such an age appears either as enrichment within immanence, i.e., the discriminating consumption of the goods and services of society, such as courses in personality enrichment, creative play, and self-growth through group interaction, etc.—or through the prime joys of the age, self-transcendence through science and art.

The pleasure of such transcendence derives not from the recovery of self but from the loss of self. Scientific and artistic transcendence is a partial recovery of Eden, the semiotic Eden, when the self explored the world through signs before falling into self-consciousness. Von Frisch with his bees, the Lascaux painter with his bison were as happy as Adam naming his animals.

I say “partial recovery of Eden” because even the best scientist and artist must reenter the world he has transcended and there’s the rub: the spectacular miseries of reentry—especially when the transcendence is so exalted as to be not merely Adam-like but godlike.

It is difficult for gods to walk the earth without taking the forms of beasts.

It is even more difficult for one god to get along with another god. Freud not only could not get along with the Jewish God but frothed and fell out when rivaled by a fellow transcender like Carl Jung.

Two gods in the Cosmos is one too many.

Thus, transcendence, like immanence, has its own scale of enrichment and impoverishment.

Different Reentry Problems of Artist and Art-Receiver: Mainly Quantitative

It is one thing to write

The Sound and the Fury,

to achieve the artistic transcendence of discerning meaning in the madness of the twentieth century, then to finish it, then to find oneself at Reed’s drugstore the next morning. A major problem of reentry, not solved but anaesthetized by alcohol.

It is something else to listen to a superb performance of Mozart’s Twenty-first Piano Concerto, to come to the end of it, to walk out into Columbus Circle afterwards. At best, a moderately sustained exaltation; at worst, a mild letdown.

Question:

In the light of the above description of the semiotic predicament of the self—its unspeakableness in a world of signs—and in the light of the need of the self to become a self and, under the exigency of truth, to become its own self, that and no other—and in the light of the forces of impoverishment and enrichment as well as self-deception, which of the following self-identities would strike you as being (1) the most impoverished, (2) the most enriched?

(a)

An Archie Bunker type who lives in Queens

(b)

A mathematical physicist working as a fellow at the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton

(c)

An Alabama Baptist

(d)

A New York novelist removed to a pre-revolutionary Connecticut farmhouse where he is living with his fifth wife

(e)

A Japanese Zen master recently removed from Kyoto to La Jolla

(

f

) An American Zen postulant recently removed from Chicago to Kyoto

(g)

A Dublin Catholic

(h)

A Belfast Protestant

(i) A

housewife who watches five hours of soap opera a day

(j) A

housewife who attends a well-run consciousness-raising group

(k) A

member of the Tasaday tribe in the Philippines before its discovery by the white man

(l) A

Virginia Episcopalian

(m)

An Orthodox Jew

(n)

An unbelieving Ethical Culture Jew

(o) A

Southern poet who has sex with his students

(p) A

homosexual poet who calls himself a “flaming fag”

(q) A

homosexual accountant who practices in the closet

(r) A

four-year-old child

(s) A

seven-year-old child

(t) A

twelve-year-old child

(u)

An Atlanta junior executive who fancies he looks like Tom Selleck, dresses Western, and frequents singles bars

(

v

) A housewife who becomes fed up, walks out, and commits herself totally to NOW

(w) A

housewife who sticks out a bad marriage

(x) A

New Rochelle commuter who quits the rat race, buys a ketch, and sails for the Leeward Islands

(y)

A New York woman novelist who writes dirty books but is quite conventional in her behavior

(z)

A Southern woman novelist who writes conventional novels of manners and who fornicates at every opportunity

(aa)

A Texan

(bb)

A KGB

apparatchik

(cc)

A white planter in Mississippi

(dd)

A black sharecropper in Mississippi

(ee)

A Fourth Degree Knight of Columbus

(ff)

None of the above, for reason of the fact that, whatever the impoverishing and enriching forces, it is impossible so to categorize an individual self—except possibly

(r),

and

(bb),

but even there, one cannot be sure. As anyone knows, a person chosen from any of the above classes may turn out against all expectations to be either a total loss as a person or that most remarkable of phenomena, an intact human self

(

CHECK ONE OR MORE

)

*

Semiotics might be defined broadly as the science which deals with signs and the use of them by creatures. Here it will be read more narrowly as the human use of signs. Other writers include animal communication by signals, a discipline which Sebeok calls zoo-semiotics. But even the narrow use may be too broad. There is this perennial danger which besets semiotics: what with man being preeminently the sign-using creature, and what with man using signs in everything that he does, semiotics runs the risk of being about everything and hence about nothing.

At best a loose and inchoate discipline, semiotics is presently in such disarray that all sorts of people call themselves semioticists and come at the subject from six different directions. Accordingly, it seems advisable to define one’s terms—there is not even agreement about what the word

sign

means—and to identify one’s friends and foes.

The friends in this case, or at least the writers to whom I am most indebted, are: Ernst Cassirer, for his vast study of the manifold ways in which man uses the symbol, in language, myth, and art, as his primary means of articulating reality; Charles S. Peirce, founder of the modern discipline of semiotics and the first to distinguish clearly between the “dyadic” behavior of stimulus-response sequences and the “triadic” character of symbol-use; Ferdinand de Saussure, another founding father of semiotics, for his fruitful analysis of

the human sign as the union of the signifier

(signifiant)

and the signified (

signifié);

Hans Werner, who systematically explored the process in which the signified is articulated within the form of the signifier; Susanne K. Langer, who, from the posture of behavioral science, clearly set forth the qualitative difference between animal’s use of signals and man’s use of symbols.

*

I am grateful for the important distinction, clearer in the German language and perhaps for this reason first arrived at by German thinkers, between

Well

and

Umwelt,

or, roughly, world and environment, e.g., von Uexkull’s

Unwelt

as, roughly, the significant environment within which an organism lives, and Heidegger’s

Welt,

the “world” into which the

Dasein

or self finds itself “thrown”; also, Eccles’ “World 3,” the public domain of signs and language within which man—uniquely, according to Eccles—lives.

The foes? If there are foes, it is not because they have not made valuable contributions in their own disciplines, but because in this particular context, that of a semiotic of the self, they are either of no use or else hostile by their own declaration.

The first is the honorable tradition of American behaviorism, once so influential, and latterday behaviorist semioticists like Charles Morris—honorable because of their rigorous attempt as good scientists to deal only with observables and so to bypass the ancient pitfalls of mind, soul, consciousness, and self which have bogged down psychologists for centuries. I start from the same place, looking at signs and the creatures which use them.

My difficulty with the behaviorists is that they rule out mind, self, and consciousness as inaccessible either on the doctrinal grounds that they do not exist or on methodological grounds that they are beyond the reach of behavioral science.

It is not necessarily so. The value of Charles Peirce and social psychologists like George Mead is that they underwrite the reality of the self without getting trapped in the isolated autonomous consciousness of Descartes and Chomsky. They do this by showing that the self becomes itself only through a transaction of signs with other selves—and does so, moreover, without succumbing to the mindless mechanism of the behaviorists.

The other semiotic foe is French structuralism—some of its proponents, at least—and its whimsical stepchild “deconstruction.” The structuralists, in high fashion—at least until recently—seek to apply the methods of structural linguistics to such diverse matters as literature, myth, fashion, even cooking. Whatever the virtues of structuralism as a method of linguistics, ethnology, and criticism, it is the self-proclaimed foe, on what seem to be ideological grounds, of the very concept of the human subject. Lévi-Strauss boasts of the dehumanization which his structuralism implies. Michel Foucault argues that with the coming of semiotics the concept of the self has vanished from our new view of reality.