Lost in the Cosmos: The Last Self-Help Book (11 page)

Read Lost in the Cosmos: The Last Self-Help Book Online

Authors: Walker Percy

Tags: #Humor, #Essays, #Semiotics

This triad is irreducible. That is to say, it cannot be understood as a sequence of dyads, as could the events, say, when Miss Sullivan spelled C-A-K-E into Helen’s hand and Helen went to look for cake—like one of Skinner’s pigeons.

At any rate, a triadic event has occurred and it is unprecedented in the Cosmos.

Thus, there is a sense in which it can be said that, given two mammals extraordinarily similar in organic structure and genetic code, and given that one species has made the breakthrough into triadic behavior and the other has not, there is, semiotically speaking, more difference between the two than there is between the dyadic animal and the planet Saturn.

Certain new properties appear. For example, all triadic behavior is

social

in origin. A signal received by an organism is like other signals or stimuli from its environment. But a sign requires a sign-giver. Thus, every triad of sign-reception requires another triad of sign-utterance. Whether the sign is a word, a painting, or a symphony—or Robinson Crusoe writing a journal to himself—a sign transaction requires a sign-utterer and a sign-receiver.

Other new properties appear, such as the relation between the utterer and the receiver, which are subject to such familiar variables as “intersubjectivity” (I-thou) and “depersonalization” (I-it).

A particularly mysterious property is the relation between the sign (signifier) and the referent (signified). It is expressed by the troublesome copula “is,” when Helen said that the perceived liquid “is” water (the word). It “is” but then again it is not. Herein surely is the root of all the troubles Stuart Chase spoke of when he said that his cat had no dealings with such a relationship and therefore was smarter or at least saner than humans.

Another unique property of the sign-user, of special significance here, is that as soon as he crosses the triadic threshold, he not only continues to exist in an environment but also has a

world.

The

world

of the sign-user is not identical to its environment or the Cosmos.

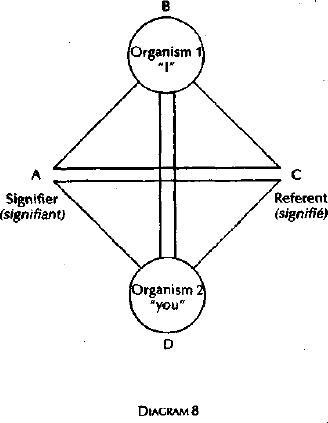

Relation AC—your giving a name to a class of objects to make a sign, and my understanding or misunderstanding of such a naming—cannot be understood as a dyadic interaction.

Relation BD—the I-you intersubjectivity of an exchange of signs—cannot be understood as a dyadic interaction.

These are two conjoined triadic events which always happen in any exchange of signs, whether in talk, looking at a painting, reading a novel, or listening to music. It allows for such peculiar properties of triadic events as understanding, misunderstanding, truth-telling, lying.

VI

The first Edenic world of the sign-user

Miss Sullivan (writing of Helen Keller): As the cold water gushed forth, filling the mug, I spelled “w-a-t-e-r” in Helen’s free hand. The word coming so close upon the sensation of cold water rushing over her hand seemed to startle her. She dropped the mug and stood as one transfixed. A new light came into her face. She spelled “w-a-t-e-r” several times. Then she dropped on the ground and asked for its name and pointed to the pump and the trellis, and suddenly turning around asked for my name. I spelled, “Teacher.” Just then the nurse brought Helen’s little sister into the pump-house, and Helen spelled “baby” and pointed to the nurse. All the way back to the house she was highly excited,

and learned the name of every object she touched,

so that in a few hours she added thirty new words to her vocabulary. Here are some of them:

Door, open, shut, give, go, come,

and a great many more.

*

Roger Brown and Ursula Belhigi (writing in “Three Processes in the Child’s Acquisition of Syntax”): Some time in the second six months of life most children say a first intelligible word. A few months later most children are saying many words and some children go about the house all day long naming things (

table, doggie, ball,

etc.) and actions

(play, see drop,

etc.)

†

Philip E. L. Smith: Having inherited from more primitive ancestors large and efficient brains, as well as a serviceable technology, these new humans proceeded to make a quantum jump greater than anything seen before in a comparable length of time. In esthetics, in communication and symbols, in technology and adaptive efficiency, and perhaps in newer forms of social organization and more complex ways of viewing their fellows, these first modern men went on to effect a transformation worldwide in its impact.

*

The signal-using organism has an environment.

The sign-user has an environment, but it also has a

world.

The environment of an organism is those elements of the Cosmos which affect the organism significantly (Saturn does not) and to which the organism either is genetically coded to respond or has learned to respond. There are many gaps in an environment, i.e., there are elements which are without significant effect. A honey bee takes account of the bee dance of another bee indicating the direction and distance of a nectar source, but not of a grouse dance.

The sign-user has a world.

The world is segmented and named by language. All perceived objects and actions and qualities are named. Even the gaps are named—by the word

gaps.

An African Bushman has hundreds of names for plants which are either noxious or medicinally beneficial. But he also has a word

bush

to name all other plants. The Cosmos is accounted for willy-nilly, rightly or wrongly, mythically or scientifically, its past, present, and future. All men in all cultures know what is under the earth, what is above the earth, and where the Cosmos came from.

The sign

Canada

is part of the world of most sign-users. It can signify whatever lies at hand to be signified, either a place and a people one knows or a large pink place on a map transected by longitudes and latitudes.

If there is an unknown territory in the heart of Africa, it is labeled as such on maps and known to sign-users as “unknown territory.”

A cat has no myths and names no real or imaginary beings. It responds to the Cosmos exactly as it has learned or been programmed to respond.

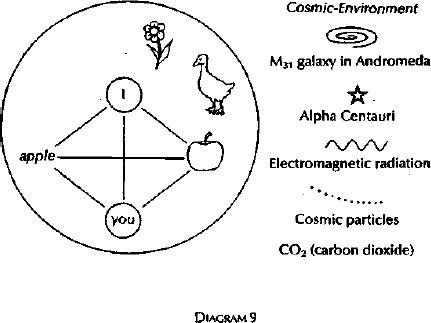

For the sign-user, a world is imposed upon the Cosmos—to which he still responds like any other organism.

For example, he still responds to signals, to heat, light, hunger, sudden noises, perhaps also to female pheromones, perhaps even to the magnetic field of the earth and the gravitational attraction of the moon. But there are other segments of the Cosmos to which he does not respond, even though astrologers say he does.

The environment has gaps. But the world of the sign-user is a totality. The Cosmos is totally construed by signs, whether the signs be the myth of Tiamat, Newtonian cosmology, or through the auspices of such popular signifiers as “outer space,” “out there,” “the heavens,” “the sky,” “stars,” and so on.

Not all items of an environment are part of the world. A noxious element—say, an increase in ultraviolet radiation—is a significant environmental factor and may cause skin cancer. But it is unknown to the patient and not part of his world. But the signs

unicorn

and

boogerman

may be very much a part of a person’s world and yet have no known counterpart in the Cosmos.

The Strange World of the Triadic Creature

Note some odd things about the self’s world. One is that it is not the same as the Cosmos-environment. The planet Venus may be a sign in the self’s world as the evening star or the morning star, but the galaxy M31 may not be present at all. Another oddity is that the self’s world contains things which have no counterpart in the Cosmos, such as centaurs, Big Foot, détente, World War I (which is past), World War III (which may not occur). Yet another odd thing is that the word

apple

which you utter is part of my world but it is not a singular thing like an individual apple. It is in fact understandable only insofar as it conforms to a rule for uttering

apples.

But the oddest thing of all is your status in my world. You—Betty, Dick—are like other items in my world—cats, dogs, and apples. But

you have

a unique property. You are also co-namer, co-discoverer, co-sustainer of my world—whether you are Kafka whom I read or Betty who reads this. Without you—Franz, Betty—I would have no world.

VII

The world of the sign-user is a world of signs.

The sign, as Saussure said, is a union of signifier (the sound-image of a word) and signified (the concept of an object, action, quality).

If you protest that your world does not consist of signs but rather of apples and trees and people and stars and walking and yellow, Saussure might reply that you don’t know any of these things but only a sensory input which your brain encodes as a percept, then abstracts as a concept which is in turn encoded and “known” under the auspices of language.

Take the sign

apple.

It consists both of the sound-image

apple

and also of a kind of general impression of apples you have known, embodying qualities of roundedness, redness, shine, texture, and sound of apple flesh at bite and pop of apple-skin against teeth, tart-tang taste, and so on.

*

One’s world is thus segmented by an almost unlimited number of signs, signifying not only here-and-now things and qualities and actions but also real and imaginary objects in the past and future. If I wish to catalogue my world, I could begin with a free association which could go on for months:

desk, pencil, writing, itch, Saussure, Belgian, minority, war, the end of the world, Superman, Birmingham, flying, slithy toves, General Grant, the 1984 Olympics, Lilliput, Mozart, Don Giovanni, The Grateful Dead, backing and filling, say it isn’t so, dreaming …

The nearest thing to a recorded world of signs is the world of H. C. Earwicker in Joyce’s

Finnegans Wake.

VIII

In a sign, the signifier and the signified are interpenetrated so that the signifier becomes, in a sense, transformed by the signified.

Saussure gave a formal analysis of the dual nature of the sign. It remained for Werner and Kaplan and other writers to describe the dynamic process by which the signifier and signified are interpenetrated and the former transformed.

If you do not believe that the word

apple

has been transformed by the percept

apple,

do this experiment: repeat the word

apple

aloud fifty times. Somewhere along the way, it will suddenly lose its magic transformation into appleness and like Cinderella at midnight become the drab little vocable it really is.

Further evidence of the interpenetration of signifier and signified is false onomatopoeia.

Words like

boom, pow, tick-tock

are said to be onomatopoetic. But what about these words:

spatter, slice, brittle, limber, blue, yellow, high, low, rattle?

Many people would say that there is some resemblance between these words and the things they signify.

Blue

sounds more like blue than

yellow. Brittle

sounds brittler than

limber.

But there is no such resemblance. Or rather, what resemblance there is, is far more remote and problematical than it appears. The resemblance occurs because the signifier and signified have been interpenetrated through use by the sign-user.