London's Shadows: The Dark Side of the Victorian City (41 page)

Read London's Shadows: The Dark Side of the Victorian City Online

Authors: Drew D. Gray

The chief official who is responsible for the detection of the murderer is as invisible to Londoners as the murderer himself. You may seek for Dr. Anderson in Scotlandyard, you may look for him in Whitehall-place, but you will not find him, for he is not there ... No one grudges him this holiday. But just at present it does strike the uninstructed observer as a trifle off that the chief of London's intelligence department in the battle, the losing battle which the police are waging against crime, should find it possible to be idling in the Alps.44

Anderson's absence was being used as a stick with which to beat the home secretary and chief commissioner, however, it is questionable what the titular head of CID would have done differently if he had not been abroad or unwell. What does seem strange from a modern perspective is that he was not relieved of duty and someone else put in command. The problem of the Met would seem to have been one of co-ordination and leadership rather than the incompetence that has so often been alleged.

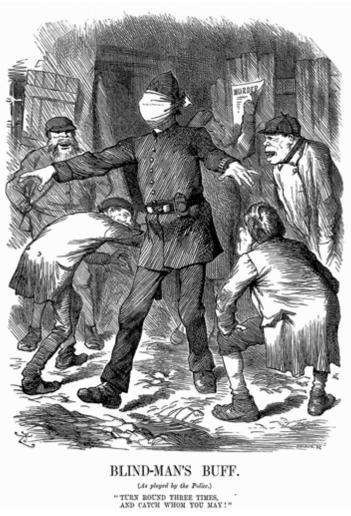

Figure 10 `Blind-man's buff', Punch, September 1888.4s

The Ripper investigation has had a great deal of criticism, both from contemporaries and more recent histories as a contemporary cartoon from Punch illustrates (Figure 10). However, much of this criticism is unfair given the limited resources available to the police in the 1880s. The late Victorian police force was not as well provisioned with technology as their twenty-first century descendants: no DNA or crime pattern analysis, no offender profiling, no CCTV, no squad cars or mobile phones. Even fingerprinting was not to arrive until the last years of the century and the science of blood typing was yet to be developed. So the notion of forensic science was a distant pipedream for the detectives trailing the Whitechapel murderer. Given their relative infancy of detection techniques the police needed to catch the killer in the act.

Warren appointed Chief Inspector (CI) Donald Swanson to head the investigation while Abberline was brought in to lead the inquiry on the ground, as he was familiar with the area having been stationed there before moving to Scotland Yard.46 The death of a prostitute was not an unusual event in the East End but violent deaths and murders were far from commonplace in the period and we should again be wary of believing the rhetoric of much of the popular press that was quick to point to the lawlessness and brutality of life in the poorer districts of the capital.

In terms of police procedure, Swanson recorded that a number of initiatives were taken by the police in the wake of the murders. House-to-house inquiries were made and 80,000 pamphlets asking for information were delivered. Common lodging houses in the area were visited and over 2,000 lodgers questioned. The Thames River Police looked into the movements of ships, since several witness statements had suggested that the killer had the look of a sailor (most probably a foreigner from the Portuguese merchant fleets or a `Laskar'). As a result of their inquiries the police took 80 persons in for further questioning, while 300 other `suspicious characters' were investigated. Butchers and slaughtermen had fallen under suspicion given their relationship with sharp knives and the cutting up of bodies. Whitechapel had been closely associated with the meat trade for centuries with cattle being driven there from Smithfield Market for slaughter. The large Jewish community was also served by many kosher butchers, or shochets. Therefore many butchers and those working in the related trades were interviewed and the `characters of the men employed [therein] enquired into' The police also looked into the movement of visitors to the area, such as a group of `Greek Gipsies; the many foreign street entertainers and the `Cowboys' and `Indians' from `Buffalo' Bill Cody's visiting American exhibition. Much of this was predicated on the notion that an Englishman could not have committed such an atrocious series of crimes.

Many arrests were made, some of them stupid ones. The widening police search in some ways revealed the pressure and desperation the Met faced in trying to prevent further tragedies and catch the murderer. In the aftermath of Annie Chapman's death Edward Quinn had been drinking at a bar near the Woolwich Arsenal. On his way to the bar he had tripped and fallen in the street, bruising and cutting his face and hands. His appearance was such that one of his fellow drinkers accosted him and told him `I mean to charge you with the Whitechapel murders' Quinn tried to laugh it off but eventually he was taken to the nearest police station and sent before the magistrate at Woolwich Police Court. There he protested his innocence declaring: `Me murder a woman! I could not murder a cat, which drew some laughter from the courtroom. Quinn was released, another unfortunate victim of the fervor that surrounded the killings."

Advice came forward from psychics and spiritualists; a relatively new and widely discredited `science' that attracted those people, like Madame Blavatsky, to the idea that the spirit world could offer answers for the living. But the advances of these `meddlers' were largely ignored by detectives who were sifting through the growing piles of information and leads relating to the case. One of the more bizarre and disturbing aspects of the Ripper case was the huge number of hoax letters and false leads that were sent to the police via the Central News Agency and the London press. Commissioner Warren looked into the possibility of using bloodhounds but this became a bit of a farce: two dogs were borrowed and underwent some training but it would have been impossible to expect a bloodhound to follow a trail through the streets of East London with all the competing scents and the total failure to preserve the crime scene. It was also suggested that the police should photograph the eyes of the victim. It was believed, by some, that the retinas of dead persons retained the image of the last person they had seen before death - in this case hopefully that would have been the murderer. However bizarre this may seem the home secretary did write to Warren after the `double event' to ask if it had been attempted - it had not. More sensibly, it is possible that the police may have issued an order to prostitutes, following Catherine Eddowes' death, to stay off the streets or effectively lose police protection. No order has survived in the police file but no murders `on the street' happened after October - Mary Kelly was killed indoors. Police constables also fitted strips of rubber to their hobnailed boots to reduce the noise; plainclothes detectives prowled the streets and infested the local pubs, and it was suggested that beat bobbies should disguise themselves as women to entrap the killer.

There was an ongoing argument about the value of offering rewards for information with Warren, initially at least, very much against it. The local chairman of the Whitechapel Vigilance Committee, George Lusk, accused the government and police of double standards in not stumping up a reward when they had been quick to do so after Lord Cavendish's murder by Irish republicans years earlier. To many in the East End it seemed that elite lives were given a much higher value than those of the poor `unfortunates' that serviced the sexual needs and desires of poor and well-to-do male Londoners. Following the murder of Catherine Eddowes on City territory in Mitre Square and a well-attended public meeting where the government and police were loudly criticized, the City of London Police and the lord mayor put up rewards of £500. Warren again told Matthews that a reward was `of no practical use' before then advocating one of £5,000. Matthews smelt a rat, and in a private letter he complained that: `Anybody can offer a reward and it is the first idea of ignorant people. But more is expected of the CID. Sir C. W. will not save himself, or put himself right with the public, by merely suggesting that. 141

In the eighteenth century rewards were commonplace. Individuals could earn rewards from the successful prosecution of felons for a number of property crimes including highway robbery and horse theft.49 This had led to corrupt practices and the emergence of blood-money scandals, the last of which had been exposed in 1816 and 1818. Concerns about entrepreneurial policing had been voiced in the debates about the creation of a professional force and the government was understandably reluctant not to return to the practice in the 1880s. However, some individuals - Samuel Montagu MP and George Lusk himself - did offer private rewards for information about the Whitechapel murders.50 The home secretary himself was clear that offering a reward would be a retrograde step, and he told the House of Commons his reasons for this. The Home Office had frequently offered rewards but had abandoned the practice in 1884 after a conspiracy to conceal a bomb at the German Embassy (and then frame an individual using planted evidence) was exposed. Matthews went on to add, with some justification given the numerous examples of persons being accused in the streets, that while there might be occasions when rewards were necessary (for example, to illicit information about the whereabouts of the murderer if his identity became known):

In the Whitechapel murders, not only are these conditions wanting at present, but the danger of a false charge is intensified by the excited state of public feelings'

The panic that was induced by the killings and the police's failure to catch the murderer manifested itself in a number of ways and touched areas far beyond the capital. An elderly man walking in an unspecified mining district of England was accosted by a group of `seven stout collier lads. They accused him of being Jack the Ripper' and demanded he `come along wi' us' to the nearest police station. In Whitechapel a young chestnut seller reported a bizarre encounter with a man who claimed to know a great deal about the killing of Mary Kelly. The stranger was dressed `like a gentleman' complete with tall silk hat and a black shiny bag that apparently contained, `Something the Ladies don't like'.'' A German visitor walking down the Whitechapel Road was chased by a mob after a woman stared into his face and screamed `he's Jack the Ripper!' and a plainclothes police officer suffered similar manhandling by local `roughs' who mistook him for the notorious killer on account of his `low broad-brim hat of rather singular appearance'53 An arrest was made on the Old Kent Road when a man left a bag at a public house that was found to contain a variety of sharp implements including a 'very sharp dagger' and two pairs of `very curious looking Meanwhile even as far away as Glasgow the police were warned to be on their guard at night; `if they hear any cry of distress, such as "Help," "Murder," or "Police," they are to hasten to the spot at once. This latter request seems somewhat unnecessary since presumably they might have been expected to undertake that particular task without the need for a circular to remind them.55

It should be remembered that aside from the Ripper inquiry the Met still had to continue to perform a great deal of mundane daily tasks. The Pall Mall Gazette's concerted attack on the London force included a detailed analysis of police numbers and roles. The Met numbered some 13,315 men in 1888 and 1,500 of these were patrolling the streets in four-hour shifts between 6 a.m. and 10 p.m. before 5,000 night officers came on to relieve them. A further 464 officers were stationed at fixed points throughout the capital during the day. Licensed cabs and other vehicles had to be checked, letters and correspondence read and answered, inquiries into crimes followed up and recorded. The Pall Mall Gazette noted that:

In the course of the twenty-four hours they will take into custody 181 persons, of whom 40 will be drunk and disorderly, 16 simply drunk, 10 will be disorderly persons, 8 will be disorderly prostitutes, while about 4 will be arrested merely as suspicious characters, and 12 as vagrants. One-half of the arrests will be for offences against order, the other half will be criminal. Taking one day with another the police run in every twenty-four hours about 30 thieves, 18 persons guilty of assault, while there are nearly half-a-dozen persons locked up for assaults on the police nearly every day all the year round.16

This range of activity is echoed by the records of the Thames Police Court as we saw in the previous chapter. From the surviving ledgers of the court we can see that in September 1888 policemen were bringing in large numbers of drunks, disorderly persons, prostitutes and petty thieves including a number of young boys found guilty of setting off fireworks in the streets. Many of those appearing had been accused of assault - sometimes on the police as a subsidiary to being arrested for drunkenness. The Pall Mall Gazette noted that these latter assaults nearly always resulted in convictions and the magistrates at the Thames Police Court fined offenders 10s or sent them to gaol. Overall the paper praised the average bobby on the beat, ending its report on police duties with the comment that `sufficient has been said to show that they do a very good day's work every twenty-four hours'.5' The Graphic had echoed these sentiments in 1887. Although it acknowledged that within a body of men as large as that of the Metropolitan Police there were bound to be a 'few erring mortals in their midst' there were also `men of pluck and fibre, doing their duty honestly, valiantly and well' .51

Victorian police officers in the capital were largely drawn from the ranks of the working classes, as Haia Shpayer-Makov's important study of the late Victorian force has established.59 The constituency for police officers was the same as that for the ranks of the army - steady, reliable men who would obey their social superiors and not question orders. The early police commissioners believed that solid agricultural workers would produce the best recruits but the evidence of Shpayer-Makov's study suggests that a broader cross section of working men joined the force, many of them coming from outside of the capital. The work of a London bobby was rather dull and repetitive with an emphasis on beat patrolling over investigation and the commensurate risk of physical violence in the more dangerous areas such as St Giles and the East End. As a result, in the early years of the force many of those who had exchanged jobs as skilled members of the working classes left the Met in their droves. The force was left with `men from unskilled or semi-skilled backgrounds, for whom the police service was an avenue of upward mobility"' A career in the police represented an opportunity for steady work at a reasonable rate of pay in a period when pay and the availability of the work was subject to the fluctuations of trade and the wider economy. This probably resulted in the police being largely staffed with men of little imagination who were not well suited to the pursuit of a cunning serial murderer. However, they were generally honest, hard-working and physically strong, healthy (an advantage given that in the poorer districts of London illness and malnutrition were commonplace) and taller than average so that they were able to deal with most of the trouble they might encounter on the streets.