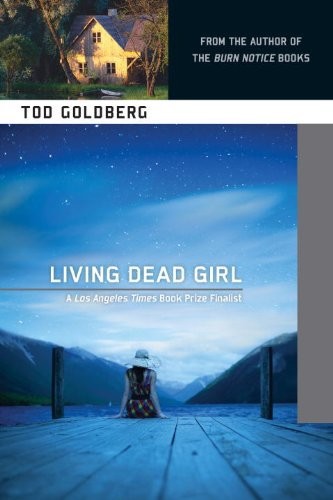

Living Dead Girl

Copyright © 2002 by Tod Goldberg

Published by

Soho Press, Inc.

853 Broadway

New York, NY 10003

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Goldberg, Tod.

Living dead girl : a novel / Tod Goldberg.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-1-61695-187-0

1. Divorced people—Fiction. 2. Missing persons—Fiction.

3. Vacation homes—Fiction. 4. Psychological fiction.

5. Mystery fiction. I. Title.

PS3557.O35836 L58 2002

813’.6—dc21

2002070586

v3.1

For Wendy, how do I explain the human heart?

All I know is that you are mine

.

Among the scenes which are deeply impressed on my mind, none exceed in sublimity the primeval forests undefaced by the hand of man. No one can stand in these solitudes unmoved, and not feel that there is more in man than the mere breath of his body.

—Charles Darwin

Contents

Chapter 1

I

am haunted by a memory I can’t recall. How long has it been since the last time I was home? Five years? A week? How many days have I spent thinking about my children, thinking about time and consequence, when I should have been concentrating on today, tomorrow, on trying to become happy?

It is fall and the air is sharp. Ginny keeps telling me to slow down so that she can really “see” her surroundings. She wants to absorb this environment, smell the flowers and the weeds and the dead things on the side of the road. She wants to be able to recreate these things exactly.

Ginny wants to make films. She says she can see a screenplay unfolding every mile we drive.

She wants to be my wife. She wants to make me understand that there is artistry in my science.

Ginny is nineteen.

“Can we stop at the Krispy Kreme?” Ginny asks. “I’ve always heard wonderful things about their doughnuts.”

I’ve already had a wife, a life: another existence separate from whatever Ginny is experiencing. She is beautiful, though. Her hair is long and blond, her stomach flat and tan. A ring dangles from her belly button and when we have sex she tells me to touch it. She tells me that the belly button is the beginning of life. I know that she is wrong. She tells me that she wants to have my baby, my babies, whatever.

I don’t tell her what I want.

Leaves have already begun to litter the streets in gold and red, and when the wind picks up they dangle in the air and I think about how much that used to mean to me: The beginning and end of life. The change of seasons.

“You know they bake them fresh,” Ginny says. We’ve pulled into the parking lot of Krispy Kreme. “Should we get a dozen?”

“No,” I say. “You don’t want to get sick on the lake.”

Ginny leans over and squeezes my cheeks. She has an extra finger on her left hand. It’s just a nub, really, beside her pinky. I noticed this the first day of class. She was sitting in the front row, drumming her fingers

on the desk, and whenever I looked up from my lectern she was beaming at me with her twisted genetic code.

“I have sea legs,” she says. “What about you,

Doctor?

”

I am not a doctor.

“Get half a dozen if they’re hot,” I say. “Otherwise we’ll gorge ourselves.”

While Ginny goes inside to order, I sit in the car. Granite City, Washington was a logging town when we bought our house near here. Instead of the Krispy Kreme donuts, Blockbuster Videos, and Del Tacos that litter the streets now, there were bars and gun shops and two small grocery stores. We’d fallen in love with the slowness of it. We were going to raise our children at home, teach them from books that we thought meant something. No silly “Dick and Jane” books. We were going to teach them to read from Chaucer.

It was silly. It is silly.

We were going to bring them up as people. Teach them as we, humans, had been taught. No state-authorized curriculum.

If they were born with vestigial tails, they would keep them.

They would never be freaks because they would know that freaks are simply the misunderstood. They would understand everything.

Ginny and I have been driving for two days. We left Los Angeles on Thursday, wound through the Bay Area, spent an angry night screwing in Klamath Falls, and then climbed through Medford, Portland, and finally into Washington.

There used to be a small pond filled with goldfish where the Krispy Kreme is now. It wasn’t the original pond, though. It was made of concrete and had a filtration system that preserved the ecosystem. It had been built on the soil of an actual “living” pond after Mt. St. Helens erupted and the ash had killed all of the fish and bugs that called the water home. There’s a plaque now that tells the history of this parcel of land.

Ginny pops out of the doughnut shop, a glazed doughnut stuffed into her mouth already.

“These are so good,” Ginny says after she sits back down. “They just came out of the fryer. You’ve gotta have one.”

“No thanks.”

“I know this is tough for you right now,” she says, “but preservation is important. You need to eat.”

I take a doughnut.

“I have to figure out how to capture this taste on film,” Ginny says. “Like in

Willy Wonka

you could just taste everything, couldn’t you?”

WE CURVE THROUGH

a narrow mountain pass toward the lake my wife and I bought our house on. Evergreen trees stand tall along the road, and Ginny has her window down to smell them. It has rained here recently, so the air is full of familiar aromas: moss, the smoky taste of damp wood.

“It’s so green here,” Ginny says. “Why isn’t it like this in LA?”

“It doesn’t rain as much.”

“I know that,” Ginny says. “But look at all this space. I mean, why can’t we just bulldoze some houses in the Valley and get some space back. Plant trees and flowers. Import some interesting African crickets or some lions and tigers. Get a little nature going.”

“The San Fernando Valley is a desert,” I say. “All the water in it comes from the Colorado River and the Owens Valley. The only things that could live there are snakes and turkey vultures.”

“Always the teacher,” Ginny says.

I admire her innocence. I do. She doesn’t understand what it takes to make life work. She hasn’t been taught that animal survival is a miracle. She’ll learn.

We’re passing familiar landmarks but Ginny doesn’t know that, either. It’s not her life.

The Branding Iron Cafe, where my wife and I made love in the men’s room. Kenny Rogers was on the

jukebox singing about the coward of the county. She’d looked me in the eye and said, “I can feel an egg dropping.”

Chance. Natural Selection. Perfecting unknown variables. Drawing Punnet Squares. It came to this.

On the sink, my arm bracing the door so no one could come in, she told me that it would be a girl. “We are discovering new places,” she said. In my mind I was Louis Leakey. We were restarting history.

“You could talk to me, you know,” Ginny says.

“I’m sorry,” I say. “I know I’m probably being distant.”

“Tell me something, Paul,” Ginny says. “Why

did

you want me to come with you?”

This is what we fought about in Klamath Falls, though it was done with different words. This time, I don’t think it will end in sex.

“I want you to be a part of this,” I say. “To understand what I’m going through, you have to see firsthand.”

“Where do you think she is?”

She

is my wife. My ex-wife. The mother of my children.

“I don’t know,” I say.

“Last night you said you loved me,” Ginny says. “Is that true, Paul? I mean, is it really true or is it just one

of those things people say when they want to end a conversation?”

“We didn’t stop talking,” I say.

Eleven fingers. It’s rare. My research tells me that it occurs in only .2% of all live births. The human hand is a precise instrument. Ginny is a mathematical improbability. Inside her, somewhere, is a strain of corrupted DNA.

“You never stop talking,” Ginny says in a coarse voice, but then leans over and kisses my neck. “Pull over. I want you in the woods.”

HERE’S THE TRUTH

. I don’t love Ginny. Her voice sounds too thick to me, like she isn’t completely a woman. When she sleeps, I often turn her over and count the vertebrae in her back. I run my finger along her rib cage, feeling the soft grooves that separate her. Her skin gets hot and throbs. I take her pulse and think that she is moving too fast, that her blood must be running backward.

I think I know where she fits in the scale of things.

She is musty with sweat now. Her flesh smells like an animal pelt. It is the dirt in her hair. The wet grass stuck to her cheek.

Ginny sits next to me but I can sense movement inside of her. She is ticking.

“I’m sorry,” I say. “I thought I knew where we turned off.”

“Don’t worry,” Ginny says. “Just stop drinking from tin cans. I don’t want you completely senile before we’re even married.”

Our rented Chevy Lumina is parked on the side of the road—a few feet from where Ginny and I had sex. She doesn’t call it sex. She calls it “banging.” It’s a generational thing, she says. I am twelve years older than Ginny. I am old enough to be her brother.

“Let me just get my bearing with this map,” Ginny says, “and I’ll direct us back out of here.”

I know where we are. We are near the place where my wife and I lived, had children, taught school. It’s the place it has always been, but the landscape has changed. This isn’t unusual.

At Piton Lake in Australia, archeologists unearthed four bodies that were twenty-five thousand years old. People had been walking on top of them for years. Picnics had taken place. There were plans to build condos. All the while these people sat underneath the ground, their history being trampled by men in floral-print shirts and women in bikinis.

One day, maybe they will carbon date the condom I threw into the bushes. Maybe they will find traces of children I never had. They will speculate about who I

was and how I lived and why I had come to this place, on this date, to have sex with someone I didn’t love.

“Okay,” Ginny says. “I know where we are.”