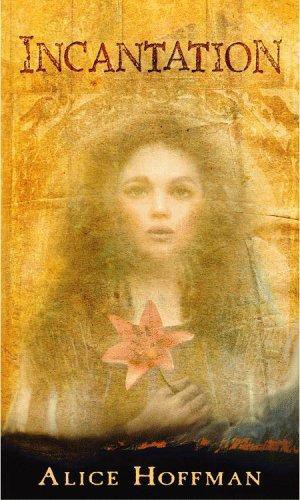

Incantation

Authors: Alice Hoffman

Tags: #Juvenile Fiction, #Historical, #Europe, #Religious, #General, #Social Issues, #Prejudice & Racism, #General Fiction

| Incantation | |

| Alice Hoffman | |

| Alice Hoffman (2006) | |

| Rating: | **** |

| Tags: | Juvenile Fiction, Historical, Europe, Religious, General, Social Issues, Prejudice & Racism, General Fiction |

Estrella is a Marrano: During the time of the Spanish Inquisition, she is one of a community of Spanish Jews living double lives as Catholics. And she is living in a house of secrets, raised by a family who practices underground the ancient and mysterious way of wisdom known as kabbalah. When Estrella discovers her family's true identity--and her family's secrets are made public--she confronts a world she's never imagined, where new love burns and where friendship ends in flame and ash, where trust is all but vanquished and betrayal has tragic and bitter consequences.

Infused with the rich context of history and faith, in her most profoundly moving work to date, Alice Hoffman's first historical novel is a transcendent journey of discovery and loss, rebirth and remembrance.

**

Contents

Text copyright © 2006 by Alice Hoffman

Illustrations copyright © 2006 by Greg Spalenka

All rights reserved.

Little, Brown and Company

Hachette Book Group USA

1271 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020

Visit our Web site at

www.lb-teens.com

First eBook Edition: October 2006

ISBN: 0-316-02261-6

[1. Prejudices—Fiction. 2. Identity—Fiction. 3. Marranos—Fiction. 4. Inquisition—Spain—Fiction.] I. Title.

I thought I knew the world.

I thought I knew myself.

I thought I knew my dearest friend.

But I knew nothing at all.

—E

STRELLA DE

M

ADRIGAL

S

PAIN

1500

Be careful

I

f every life is a river, then it’s little wonder that we do not even notice the changes that occur until we are far out in the darkest sea. One day you look around and nothing is familiar, not even your own face.

My name once meant

daughter, granddaughter, friend, sister, beloved.

Now those words mean only what their letters spell out: Star in the night sky. Truth in the darkness.

I have crossed over to a place where I never thought I’d be. I am someone I would have never imagined. A secret. A dream. I am this, body and soul. Burn me. Drown me. Tell me lies. I will still be who I am.

W

E LIVED

in a tiny village in Spain. It is gone now, but then it was called Encaleflora, the name of the lime flower, something bitter and something sweet mixed into one. It was a town that had been my family’s home for more than five hundred years, a beautiful village in the most beautiful countryside in all of Aragon.

It began on a hot day.

I was out in the garden when I smelled something burning. Not lime flowers, only pure bitterness. Cores, rinds, pits. That was the way it started. That was the way our world disappeared.

O

N THE DAY

of the burning, my dearest friend, Catalina, ran into our yard and grabbed my hand, urging me to follow her.

Let’s run to the Plaza,

Catalina said.

Let’s see what’s on fire.

Catalina was always curious, always fun. She had a laugh that reminded me of the sound of water. She was shorter than I, but even though my grandmother said Catalina’s hair was too curly and her nose was bumpy, I thought we looked like sisters.

Catalina and I were so close nothing could come between us. We had been best friends from the time we were babies. When I looked at my friend I saw not only the child she’d been and the girl that she was, but also the woman she was about to be. Other girls I knew talked behind your back and smiled at you falsely. Not Catalina. She knew who I was deep inside: I could be lazy sometimes; I believed in true love; I was headstrong and loyal, a friend until the end of time.

Because of our jet-colored hair, Catalina and I had been given similar pet names as little girls. I had been called Raven and Catalina had been Crow. Our birthdays were one week apart, and we had at last turned sixteen. We thought about our futures, how they twined around each other, as if we were two strands of a single braid of fate. Even when we were married women, we planned to live next door to each other. We thought we knew exactly what our lives were made of: still water, not a moving river.

We thought nothing would ever change.

O

N THE BURNING DAY

, we raced down to the Plaza, where we always went to fetch water. There was a well in the center of the Plaza, and the water we pulled up in wooden buckets was said to come from heaven. It was sweet and clear and so cold it made us shiver.

To the north stood the old Duke’s palace, but he was gone, and our church council reported directly to the king, Ferdinand. The palace was empty, except for the soldiers’ barracks and the center where letters could be posted. People said the ghost of the Duke came down to drink cold, clear water on windy nights and that you could hear him if you listened carefully. But today no one was drawing water from the well, not even a ghost. There were scores of men all around, but they hadn’t come for water. Soldiers had built a pyre out of aged wood. Pine and old forest oak, all of it so dry it burst into flames the moment a lit torch touched the wood.

At first I thought the soldiers were burning doves. White things were rising into the sky. I felt so sad for those poor burning birds, then I realized the burning pile was made of books. Pages flew upward, disappearing, turning to embers and ash, drifting into nothingness.

I saw a man with a red circle on his coat, crying. He had a long beard like my grandfather, but my grandfather would never cry, with tears streaming down his beard, there for all to see. The crying man was begging the soldiers not to throw his books on the fire, and they were laughing at him. A guard took a handful of ashes and tossed them onto the old man so that sparks flared all over his coat.

He’s from the

alajama, Catalina whispered about the old man.

That was the part of town where Jews lived that some called the

juderia.

Our parents didn’t allow us to go there. We were Christians. A hundred years beforehand most of the Jews in Spain had either been forced to convert or flee the country. The stubborn ones who remained and declared themselves to be Jews were the ones who lived behind gates—the red circle people who seemed willing to do anything, even die, for their precious books; people who by law could not own land, marry outside their faith, eat a meal with a Christian.

There were cinders floating down into Catalina’s black hair. She didn’t notice, so I brushed them away.

Those are his books,

Catalina said of the old man in the ashes.

The town council has posted a new decree. No Jewish books, no medical books, no magic books.

I saw the way the soldiers treated this man. As if he were a bird caught in a snare made of his own bones. His coat had caught on fire, but he no longer cried. I think he may have looked at me. I think I may have looked back.

Catalina applauded with the other onlookers in the square when a soldier threw a bucket of cold water over the old man. I merely stood there.

My mother, Abra, had taught me that all people are made from the same dust. When our days here are gone, all men and women enter the same garden. My mother had put a finger to her lips when she told me this. She taught me some of what she’d learned from her father, secret things I must never repeat. Lessons that sounded as though they would be easy, but which turned out to be difficult. How to look at stars and know their names. How to gaze into a bowl of water until it was possible to see all that existed in that one small bowl.

Once I fell asleep while gazing, and my mother laughed when I awoke with a start, my chin in the water.

I’m not smart enough to learn anything,

I had admitted.

You don’t learn such things,

my mother had said.

You feel them.

Now my mother saw me with Catalina in the Plaza. She looked shocked to see us in the middle of the rioting, in a place we shouldn’t be.

My mother had a basket of wool with her; she had been to the dye vats near the river, and her arms were tinted from her work. My mother was known for the yarn she sold. Whatever Abra did was beautiful; she had the ability to make something wondrous out of something plain. That was her talent, one I envied. Any wool spun at her wheel was finer than all the rest, even though our sheep were as silly as any others.

Sometimes I went with my mother when she called on her clients, carrying a basket of yarn that was dyed every shade of blue imaginable. Turquoise, aqua, night blue, ultramarine, bird’s egg blue, early morning blue, inside-of-a-cloud blue, pond blue, river blue, blue as all eternity. My mother’s hands were always blue, sometimes like water, sometimes like the sky, sometimes like the colors of a bird’s feathers.

There in the Plaza, my mother was like a piece of the sky coming right at me. A person should never come face-to-face with the sky. She looked as frightening as my grandmother did when she was angry. Fierce. Unrelenting. She ran over and grabbed me. There must have been sparks in my hair as there had been in Catalina’s, because my mother put her hands in my hair. She clasped my head so hard that it hurt.

My mother and I had always been more like sisters than mother and daughter, but not today. Today I was a child, one who should have known better than to be in the Plaza. Without waiting for me to explain, my mother dragged me along, tugging on my hair. My black hair that was so long I sometimes felt I had wings. Even before the other children called me Raven, I had often dreamed I could fly. I would fly until I could go no farther, so far away no one had ever been there before. In my dreams I would enter into a garden where the roses were big enough for me to curl up inside them. I would know how to decipher symbols I had never even seen in my waking life.

As we left the Plaza, I looked over my shoulder. The man with the red circle was curled up as the guards kicked him. There were no roses, only the brightness of the flames. Ashes kept falling. The Plaza was dirty and gray.

Something from deep inside the world had crept up from the well; a monster set loose in our midst. The fire was his breath; the jeers all around were his snarls. I felt something burn inside of me.

I called for Catalina, but she was too busy watching the guards to pay any attention. My mother refused to let me stay alongside my friend.

We are leaving and that’s that. Never look at other people’s bad fortune,

my mother said.

If you do, it will come back to find you instead of its rightful owner.

A

ll that day we could hear people shouting in the streets. Stones were thrown; windows were smashed; the gates of the juderia were painted red, the color of the devil’s work. In edicts posted all over the village, the town fathers declared they were sick of the Jews stealing from them, although what had been stolen was never disclosed.

Because some Jews were moneylenders, they were blamed for the town’s recent bad fortune. In truth, everyone knew Jews were only permitted to lend money because the church wouldn’t allow one Christian to lend another money. How much money could there be in such dealings? The Jews weren’t rich. In the walled-off section of town where they lived, there were no lime trees, no ivy, no gardens filled with jasmine. In summer, the heat baked the bare earth into bricks. I had seen the children looking through the wall; they wore no shoes. At night, the gate was locked, the way we locked the pens of our chickens and pigs.