Lilla's Feast (12 page)

Authors: Frances Osborne

Socially, the Howells were as deeply conventional as they believed they were not. They may have mingled with scientists on the cutting edge of change. They may have foreseen the cataclysmic political changes of the twentieth century, pointing out in their letters that “things cannot continue as they are” and discussing the likely collapse of “that wonderful house of cards which we call our Indian Empire”—even when that meant the end of the very traditions, the old order, that had nurtured them. They may have held strikingly liberal views on women’s education—it was quite extraordinary that in the 1880s and 1890s, when few women were educated at all, the family had not just allowed, but encouraged, Laura and Barbie to go to Cambridge. And, of course, each of them may have felt that their experiences in India had given them a worldly-wise perspective from which to judge. Nonetheless, on social issues, they were the puritanical sort of small “c” conservatives whose sympathies and aversions had long sustained the British class system: When it came to family pedigree, the longer the better. And on this point, they chose conveniently to ignore the fact that until Papa’s grandfather had ventured up to London and made a fortune shipping stores out to the British army in its various wars, the Howells had simply been the local butchers in Oswestry, a market town on the Welsh border. Instead, they focused on the achievements of Papa’s father, Sir Thomas Howell, who had been knighted for sorting out the shambolic logistics—or lack of them—that had left the British army without enough boots during the first bitter winter of the Crimean War.

A couple of exceptionally procreative generations—Papa was one of thirteen and appears restrained in having only six children himself—had now subdivided the family money to a pittance. This left the short-of-cash Howells deeply suspicious of other people’s fortunes, particularly those that were newly made, as the Eckfords’ money was in China. It was an unspoken but fundamentally held belief among Lilla’s in-laws that the pursuit of riches resulted in a neglect of more high-minded endeavors. “They must be fairly well endowed with this world’s goods,” wrote Papa Howell after meeting Andrew and Alice Eckford for the first time, implying that they lacked the nonmaterial, intellectual assets that were worth more.

There was certainly an element of jealousy in the Howells’ snobbery. Like Ernie, the rest of the men in the Howell family were perpetually moaning about a “shortage of funds.” When translated into English pounds and prices, Indian Civil Service and Indian army salaries were not generous. The mess bills, the uniforms, the cost of employing a valet could easily make an army officer’s career an expensive luxury rather than a gainful occupation. Ernie and his siblings, even their parents, were incessantly calculating how to live the lifestyle that they had been brought up to expect on the combination of salary and the tiny private income that each of them had. And while they whinged about the differences between extravagances and necessities, they were all aware that the Eckfords didn’t have to make such distinctions.

This must have made it all the harder for Ernie to ask Andrew Eckford for help. When Andrew wrote out checks to Lilla, Ernie must certainly have been grateful. But admitting to a successful businessman like Andrew Eckford that he couldn’t cope financially would have knocked a huge dent in his soldierly pride. The straightforward option—especially now that Lilla had her family in England—was to stick to his plan to go to India alone.

Money wasn’t the only gulf between the two families. Lilla was already well acquainted with the sharp contrast between the Eckfords’ love of luxury and the Howells’ almost spartan lifestyle. For Alice, this would have come as a shock. She may have intended the display in the house in Bedford to bring the two families closer together, but instead, it seemed to accentuate their differences.

The Eckfords’ house in Bedford was everything that the house in Kensington Gardens Square was not. Number 5 Kensington Gardens Square was an externally elegant, white-stucco terraced house containing a smattering of functional furniture. Number 14 Lansdowne Road, Bedford, was, wrote Ernie’s sister Laura after she had driven over from Cambridge to see the Eckfords, “not much to look at on the outside, but most comfortable inside.” To some extent, Laura was impressed. “[The house is] beautifully furnished. The drawing room is a perfect museum of Chinese and Japanese china, embroidery, carved work, etc.”

But this attention to visual detail heralded—as Laura might have expected—a lack of the intellectual interests that the Howells cared so much about. The Eckfords’ conversation, she nonetheless wrote, was “not particularly cultivated.” Alice Eckford in particular she found “suburban” and “full of a fussy sort of kindness which is rather distracting.” “She simply fazes me out,” continued Laura. “She has discovered the secret of perpetual motion and has in addition an unending flow of small talk. I think there is nothing as tiring as having to talk for a whole day, especially the make up kind of talk one has to keep up with a person with whom one has not really much in common.”

Poor Alice. She was trying so hard to make life easier for Lilla by being friendly and showing that her family was too rich to be ignored. Really, she would have done better if she had suggested that the Eckfords were impoverished artists with grand connections. If she had toned down the decoration, focused on her love of singing, and chatted less, maybe the Howells would have warmed to her.

Lilla’s baby was due at the end of August. By the beginning of July, she would already have felt the size of a house and been torn between a longing to be rid of the huge weight she was carrying and a growing fear of the pain that lay ahead in what was euphemistically referred to by the Howells as her “event.” The question arose as to where she should give birth and stay for her confinement afterward. The convention then was that, after giving birth, a woman should “lie in”—either stay in bed or take it very easy indeed—for six weeks.

Deeply relieved that some of her family was with her in England— even if it made her twin’s absence all the more marked—Lilla assumed that she would go to her mother in Bedford for the birth and started organizing herself to do so. But when the Howells caught wind of this, they were aghast. Lilla was now a Howell, they pointed out, as the baby she was having would be, too. She should therefore be with her husband’s family for her “troubles.” Perhaps Ernie’s family did not quite trust Lilla’s “suburban” mother to do things in the proper way or held some suspicion that she might have picked up unorthodox childbearing practices in China. In any case, they professed amazement that Lilla could have been foolish enough to think that she should give birth anywhere but in a Howell household. London was regarded as unhealthy for a newborn, particularly in the summer, so it was decided that Lilla would go to some cousins of Ernie’s near Cromer, on the Norfolk coast.

Cromer may have been a fashionable seaside resort like Chefoo, but Norfolk is nothing like Shantung. Instead of a town sheltered by hills and beaches nestling between rocky coves, the Norfolk coastline is bare and flat. The only undulations along the East Anglian shore and inland are a few dunes whose sand has been whipped up into great piles by the wind and the dips that mark the great watery channels that crisscross the countryside—the marshlands known as the Norfolk Broads. Barring a few tufts of tough, shrubby grass, there is little to stop the great North Sea winds sweeping down from icy Scandinavia and leveling the landscape. Even in August, the hottest month of the year, Norfolk requires a thick fisherman’s sweater. It is not a cozy place to give birth to a first child.

Not that Lilla can have cared. Ernie was still intending to go back to India without her. And although her mother was now there to encourage Lilla to hold back a little, not serve herself up to Ernie on a plate, telling her that he would come round once he held his child in his arms, Lilla must have been desperate to do anything to make herself seem less of a burden and easier to take with him. She agreed to go to Cromer.

Ernie didn’t go with her. In late July, he dispatched Lilla to his relatives and took the sleeper to Scotland. There, he joined his father, who had already taken up residence at the Royal and Ancient Golf Club in St. Andrews. While Lilla was left among strangers in an unfamiliar place to grow larger, more exhausted, and increasingly anxious about what lay ahead of her in childbirth, Ernie and Papa settled down for a month or so of father-and-son golf.

Alice followed her daughter from Bedford to Cromer, taking Andrew and their two girls with them. She booked rooms for the family in one of the hotels and hovered as close as she could without interfering with the Howells’ arrangements and upsetting matters more.

Again, it was Barbie’s lone voice, from miles away in India, that spoke up for Lilla. “For this event of hers she seems to have been the last person to have been consulted, though one would have thought on this one occasion at least she was the first person to consider.”

Perhaps, if they had arrived in time, Barbie’s words would have roused a flicker of conscience among her family back in England. But, of course, it was yet another month before they were read.

The baby was late. Luckily perhaps, for it was only toward the end of August that Ernie decided to return south. Papa was reluctant to see him go: “I wish Ernie could have stayed longer with me.” Ernie reached Norfolk in the last days of the month. Papa planned to follow him shortly.

The first week of September passed. There was no sign of the baby. The second week dragged on with Lilla cumbersome, barely able to move, simply waiting on tenterhooks for the pain to begin. By the time September reached its third week, Alice decided to intervene. In her opinion—and she had borne six children herself—a bit of movement was what was needed. She took Lilla out for a carriage drive. The “carriage” was a fairly rudimentary pony and cart. Nonetheless, as my grandfather, Lilla’s son, told me again and again, Alice set off at a rapid pace.

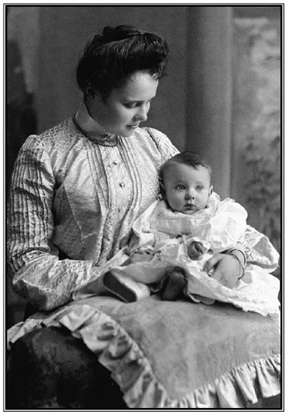

Lilla and Arthur, Bedford, 1902

It’s unclear whether it was a surprising corner or another vehicle that caused the crash. But shortly after leaving the house, the horse bolted and the pony cart ended up in the ditch. Lilla, shaken by the fall, felt her stomach begin to contract. Alice’s plan, in a roundabout way, had worked.

The baby, my grandfather, was a boy. Given the less-than-perfect state of Ernie and Lilla’s relationship, this was probably a good thing. Ernie regarded baby girls as “petticoats.” In any case, Lilla’s in-laws were delighted. The baby was the first boy with the surname Howell to be born in his generation, and, even better, the few wisps of hair on the top of his head were clearly the same reddish color that Ernie and Papa Howell were so proud to bear. For once, Lilla appeared to have done something right, and glowing with pride and keen to preserve this new state of affairs, she readily agreed to christen her son Arthur after Ernie’s father.

Lilla’s state of grace in having produced a son and heir was short-lived. Alice had seized the opportunity of being with Lilla for the birth and had whisked her straight back to Bedford. But the Howells must have wanted Ernie’s son back. Just one week after the birth, when Lilla should still have been confined to bed, she made the day-long journey back from Bedford to Ernie’s cousins in Norfolk. There, when she was worn out from the trip and separated from her own family, things rapidly went downhill.

A couple of afternoons later, Lilla was alone with baby Arthur when she began the usual struggle to persuade him to feed from her breast. Muddled by the soul-emptying exhaustion of childbirth and moving around the country, she was turning the tiny child around every way she could think of to find an angle at which he could latch on when the Howells’ baby nurse came into the room. The nurse was horrified, as Lilla later said, to see her “trying to feed the baby upside down.” She snatched Arthur from her and advised the family that Lilla was unfit to look after the child. From then on, the times at which Lilla could see her baby—under strict supervision—were limited.

Lilla was devastated. To take a newborn child from its mother is to tear that mother apart. Having given birth so recently, Lilla ached in every cell of her body to hold her son in her arms and pull him close to her, dulling the physical pain and emotional turmoil that can make a new mother feel like she has been run over by a juggernaut. And she would have still felt so physically joined to her baby that whenever the nurse took Arthur from her and swept him out of her room, it would have felt as though, like a medieval torturer, she had reached in and taken hold of Lilla’s innards, dragging them behind her as she and the baby left the room. Each time Lilla watched Arthur’s tiny pudgy hands and face disappear out of view, I’m sure she felt that part of her died.

A few days later, bad news came from India. Ernie’s sister Barbie had also given birth to a healthy boy—Alan Fitzroy, known as Roy— just two days after Lilla. But she had since fallen dangerously ill with a postpartum infection. Such infections are a common complication of childbirth today—though they can usually be cured by a swift course of antibiotics. Back in 1902, the only way to recover was to ride the infection out. Or, in the worst cases, be operated on—putting the mother at risk of yet more infection. The wire that the Howells received in England told them that Barbie’s temperature had already been climbing steadily above 104 degrees Fahrenheit for four days. The absolute maximum amount of time that a person could survive with a fever at this level was eight or nine days.