Lifeline

- Dedication

- Dramatis Personae

- Prologue

- Part One Isolation

- Chapter 1

- Chapter 2

- Chapter 3

- Chapter 4

- Chapter 5

- Chapter 6

- Chapter 7

- Chapter 8

- Chapter 9

- Chapter 10

- Chapter 11

- Chapter 12

- Chapter 13

- Chapter 14

- Chapter 15

- Chapter 16

- Chapter 17

- Chapter 18

- Chapter 19

- Chapter 20

- Chapter 21

- Chapter 22

- Part Two Incentive

- Chapter 23

- Chapter 24

- Chapter 25

- Chapter 26

- Chapter 27

- Chapter 28

- Chapter 29

- Chapter 30

- Chapter 31

- Chapter 32

- Chapter 33

- Part Three Interaction

- Chapter 34

- Chapter 35

- Chapter 36

- Chapter 37

- Chapter 38

- Chapter 39

- Chapter 40

- Chapter 41

- Chapter 42

- Chapter 43

- Chapter 44

- Chapter 45

- Chapter 46

- Chapter 47

- Chapter 48

- Chapter 49

- Chapter 50

- Chapter 51

- Chapter 52

- Chapter 53

- Chapter 54

- Chapter 55

- Chapter 56

- Chapter 57

- Chapter 58

- Chapter 59

- Chapter 60

- Chapter 61

- Chapter 62

- Chapter 63

- Chapter 64

- Chapter 65

- Chapter 66

- Chapter 67

- Epilogue

- Afterword: Lifeline Origins

- Acknowledgments

- About the Authors

Kevin J. Anderson & Doug Beason

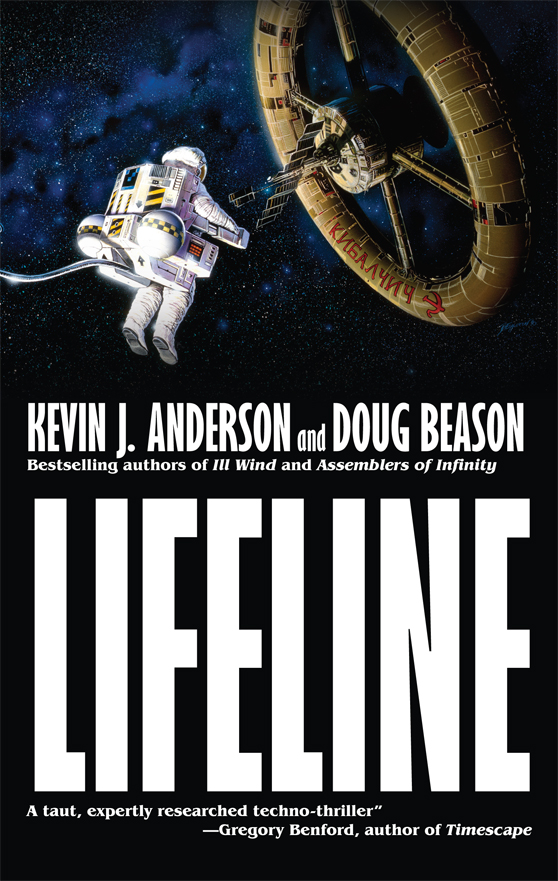

Book Description

In shock and grief the last remnants of the human race watched from space as the holocaust of war raged across the face of the Earth. Now the future rested in the hands of three fragile space colonies:

Aguinaldo

—The Philippine L-5 colony whose brilliant biochemist had engineered a limitless supply of food.

Kibalchich

—The Soviet space exploration platform that harbored a deadly secret.

Orbitech 1

—The American space factory whose superstrong weavewire could be a lifeline to link the colonies—or a cutting-edge weapon of destruction.

As allies, they could unite to rebuild a better world. As enemies, they could destroy mankind’s last hope for survival.

Lifeline

by Kevin J. Anderson and Doug Beason.

***

Smashwords Edition – 2014

WordFire Press

wordfirepress.com

ISBN: 978-1-61475-257-8

Copyright © 1990 Wordfire, Inc. & Doug Beason

Originally published by Bantam Spectra, 1990

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the express written permission of the copyright holder, except where permitted by law. This novel is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination, or, if real, used fictitiously.

This book is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This ebook may not be re-sold or given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person, please purchase an additional copy for each recipient. Thank you for respecting the hard work of this author.

Cover Art by Bob Eggleton

Cover Design by Janet McDonald

Art Director Kevin J. Anderson

Book Design by RuneWright, LLC

www.RuneWright.com

Kevin J. Anderson & Rebecca Moesta, Publishers

Published by

WordFire Press, an imprint of

WordFire, Inc.

PO Box 1840

Monument, CO 80132

***

Dedication

To my mother, Martha Grace McCluney Beason, for leading me to books. (Doug Beason)

and

To Dean Wesley Smith, for being more than just the right place at the right time. (Kevin J. Anderson)

***

Dramatis Personae

AGUINALDO (L-4)

Ramis Barrera—colonist

Agpalo Barrera—Ramis’s father

Panay Barrera—Ramis’s mother

Salita Barrera—Ramis’s brother on Earth

Dr. Luis Sandovaal—

Aguinaldo’s

chief scientist

Dobo Daeng—Luis’s assistant

Barreta Daeng—Dobo’s wife

Yoli Magsaysay—president of the

Aguinaldo

Nada Magsaysay—Yoli’s wife

Dr. Panogy—celestial mechanics expert

CLAVIUS BASE (MOON)

Dr. Kim Berenger—infirmary M.D.

Dr. Clifford E. Clancy—

Orbitech 2

chief engineer

Wiay Shen—Clancy’s chief foreman L

Dr. Philip Tomkins—

Clavius Base

chief administrator

Josef Abdallah—technician and work scheduler

Dr. Billy Rockland—group leader, celestial mechanics

Harmon Wooster—

Orbitech 2

engineer

ORBITECH 1 (L-5)

Linda Arnando—Personnel/Admin Division leader, later chief assessor for Curtis Brahms

Dr. Daniel Aiken—research scientist, biochemist

Sheila Aiken—Daniel’s wife

Stephanie Garland—Miranda shuttle pilot

Allen Terachyk—Research & Development Division leader, later chief assessor for Curtis Brahms

Duncan McLaris—Production Division leader, later acting administrator for Clavius Base

Jessie McLaris—Duncan’s daughter

Diane McLaris—Duncan’s wife

Dr. Karen Langelier—research chemist, polymers

Tim Drury—Maintenance/Services Division leader

Curtis Brahms—acting director,

Orbitech 1

Sigat Harhoosma—metallurgist

Hiro Kaitanabe—gardener

Roha Ombalal—director,

Orbitech 1

Nancy Winkowski—chemical technician and laboratory assistant, later Watcher

KIBALCHICH (L-5)

Dr. Anna Tripolk—chief biochemist, in charge of research

Commander Stepan Rvrik—

Kibalchich

commanding officer

Alexandrov Cagarin—political officer

Illimui Danskoy—activist

Grekov—technician

Orvinskad—technician

Sheveremsky—technician

***

Prologue

L-4: AGUINALDO—5 Years Before Day 1

He thought the experiment would work, but even if it failed, he knew he could bluff his way through. The Filipinos held their Dr. Luis Sandovaal too much in awe for them to doubt anything he did.

Sandovaal ignored the crowd around him. President Magsaysay stood quietly by the airlock, along with the rest of the Council of Twenty. Sandovaal stared past the group, past the habitats and experimental fields, and gazed instead upon the sweeping curve of the cylindrical colony’s far side, where Filipino children played floater-tag in the zero-G core.

Sandovaal’s whole life revolved around success: taking outrageous chances, working long hours until he felt absolutely sure his experiments would prove out. Admitting to being only “second best” seemed as bad as conceding defeat. The field of applied genetics evolved too fast for stragglers.

That had always made it necessary for Sandovaal to take certain …

chances …

with his bioengineering research so he could remain the best, the most innovative. He had come to carry on his researches at L-4, the gravitational stable point 60 degrees ahead of the Moon in its orbit, four hundred thousand kilometers away from Earth—where the rest of the planet would be safe in case anything went wrong.

That self-imposed exile had proven a blessing, giving him unlimited academic freedom and free reign to direct his own research laboratory on board the Filipino colony

Aguinaldo,

the largest of the three human stations at L-4 and L-5. The Filipinos were proud of his presence there, to the point of designating him the colony’s chief scientist.

Sandovaal drew himself up to his full five-foot stature and spoke to the crowd in front of the airlock. With his blue eyes and shock of white hair, he didn’t look much like the other

Aguinaldo

inhabitants.

“President Magsaysay, distinguished senators. Today the

Aguinaldo

is a mere shell of what is to come. Generations from now the empty fields behind you will be filled with our children’s children, and because of the design of our colony, living space will still be plentiful.

“But adequate living space does not imply that there will always be room for growing our food. Plants need open area to grow—area that will be at a premium several years from now. People will not be willing to live in crowded conditions so that their food may flourish. But I have discovered a solution. Although the

Aguinaldo

may be limited in its area, there is a way to tap an

infinite

amount of space in which to grow the crops that can sustain us.”

President Magsaysay gave the hint of a smile. “Good, Luis. The Council of Twenty are all proud of you and your accomplishments.” He swung an arm around the airlock bay. “But why did you bring us out here, away from your laboratory?”

Sandovaal nodded to his assistant. “Dobo, prepare to eject the organism.” It was a hybrid that combined the nervous system and motor capabilities of a Portuguese man-of-war jellyfish with the cellular structure of a plant—a transgenetic organism that extended Sandovaal’s research beyond the simple wall-kelp that was even now supplementing the feed for their small population of animals.

Sandovaal turned his attention back to the Council. “This problem concerned me for some time. I tried several ways of genetically forcing plants to become denser, use less light, so that they would not take up so much room. Then I realized that we have all the space and light we need outside the

Aguinaldo.”

Dobo Daeng ran his fingers over the control panel. A green lightcell changed to red. Sandovaal motioned the Council of Twenty to the viewport. The Filipinos murmured questions in low voices and crowded next to Sandovaal as they peered out the large crystal port. Sandovaal gave a smug smile.

“I have genetically altered this animal to have a dominant survival characteristic that takes advantage of its plant attributes. When it is exposed to a vacuum, the organism will increase its surface area. This allows it to capture more light and increase its ability to photosynthesize. Implanted mineral packets will allow the creature to grow—”

“In a vacuum?” interrupted Magsaysay.

“Yes. That is the point, Yoli. If this proves successful, our next step will be to have this organism grow outside.

Outside!

Think of the food source we could harvest.”

Sandovaal pushed through the Council of Twenty and moved right up to the viewport. The organism’s cigar-shaped body floated out of the airlock attached to a long tether. Stubby “wings” extended from either side of the meter-long body; lights outside the airlock illuminated the creature. It spun slowly as the line played out.

“By tomorrow the creature’s wings will have grown several centimeters. And in two weeks, they will extend for meters. If it survives that long.”

Sandovaal pressed his lips together and waited for the accolades. Magsaysay clasped his shoulder as the Council of Twenty nodded among themselves.

Sandovaal did not stay to participate in the political small talk. He had much more important tasks to attend to. He strolled back to the bioengineering lab modules, muttering to himself.

Sandovaal ignored the regular day/night schedule imposed by rotating shutters on the lightaxis. He worked until he had exhausted himself, realizing after several hours that it was Sunday and he could not expect his assistant Dobo to arrive, since Dobo’s wife would insist on attending Mass and relaxing with him. Sometimes Sandovaal didn’t understand other people’s priorities.

He returned to his own quarters and slept for little more than an hour before the insistent ringing of the door chime brought him awake again. He slid open the door, rubbing his eyes and automatically snapping at the short, florid-faced man waiting for him.

“Dobo, why can’t you—”

But Dobo seemed agitated and cut off Sandovaal’s words. The mere fact that his assistant would dare to interrupt brought Sandovaal to silence. “Dr. Sandovaal, you must come to the viewport end! Quickly! Something strange and wonderful has happened. Perhaps you can tell us what it is. The others are gathering there.”

Dobo turned and hurried back to his waiting jeepney before Sandovaal could say anything. His curiosity piqued, Sandovaal joined him. As they drove, he could see other Filipinos jetting or pedaling their way across the core to the cap on the cylinder. After parking the jeepney with the other vehicles at the wall, Dobo cleared a way through the crowd for Sandovaal.

Pressing his face against the hexagonal quartz sections, Sandovaal stared in astounded silence. He saw the familiar sea of stars, the glints of nearby debris at L-4, where the first superstructure for the new station

Orbitech 2

was under construction, the great glare of the gibbous Moon.

But he also saw a giant, translucent wisp of material covering part of the viewport. It seemed extraordinarily thin, yet extended for kilometers. Fragments hundreds of meters across tore away due to the colony’s rotation and hovered in the L-4 gravity well, where they would drift under pressure from the solar wind.

Many other people watched the flimsy material, fascinated, possibly frightened. Some looked toward Sandovaal, as if expecting him to produce a comprehensive answer after only a simple glance. He saw President Magsaysay alighting from a jeepney.

Sandovaal turned to Dobo. “Well, has anyone thought to have a piece brought inside for analysis?”

When Sandovaal did complete his inspection in the laboratory—with Magsaysay and some of the senators from the Council of Twenty breathing down his neck—he discovered that the transgenetic organism had grown far beyond even his wildest estimate.

Months later, in a simultaneous announcement to

Nature

and the

New York Times,

Dr. Luis Sandovaal presented his discovery. The original creature looked not unlike a manta ray. It puttered around, swimming in the zero-G core, eating small amounts of wall-kelp and photosynthesizing, completely innocuous. But when ejected into the hard vacuum of space, it underwent a drastic survival measure—a

transformation in which its volume expanded to maximize surface area. The tiny flippers in the body core crushed down and smeared out into a layer only a few cells thick. This let it absorb as many solar photons as possible for photosynthesis. The end result was a beautiful, but thoroughly impractical wing-like body spanning scores of kilometers: a giant organic solar sail that could live on its metabolic reserves for perhaps weeks.

Sandovaal did not admit that he had failed to produce a radical new food source—the tissue proved too thin to be of use—but instead played up the basic discovery in the field of transgenetic biology.

The Earth press and intercolony communications dubbed the life-forms “sail-creatures.” Sandovaal would have preferred something more elegant, but the name stuck.

CENTER FOR HIGH-TECHNOLOGY MATERIALS ALBUQUERQUE, NEW MEXICO

Colors rippled as Karen Langelier tuned the laser to a different wavelength. The color jumped as it locked onto the new material’s resonance structure, glowing a deep red. A long, thin liquid strand of phenolic began to crawl up the beam. She pressed the laser goggles against her high cheekbones to lean over the vacuum vessel. Afraid to breathe, she watched as the phenolic drew out, thinner and thinner, approaching the limit of visibility.

Just as she began to adjust the probe, the delicate strand broke. Globules of pulsating bubbles crashed into each other throughout the vessel, striking the walls.

“Damn!” Karen turned from the vacuum vessel. “Three strikes and I’m out today!”

The new article in the

Online Review of Scientific Instruments

seemed clear enough—laser filamentation was a well-documented process, known for decades. She had arranged the experiment to duplicate the test conditions. It wasn’t like she was new at this, either. Maybe there was some problem with the phenolic she had used.

Karen knew she would be a grouch tonight when she got home, and Ray would probably spend the evening talking about the cases in his law office. He wouldn’t even notice she’d had a bad day.

“Well, then,” Karen said out loud, “I’ll just have to make it a good day for myself.”

Expelling a breath, she turned back to the three-dimensional holotank. “Let’s walk through this one last time.” She slapped at the library control panel and called up the article again. “And I’ve got to stop talking to myself.”

As the manuscript popped into the tank, she saw that her fingers had transposed two digits on the recall memory, pulling up instead the backlog of papers from

Physical Review Letters

she still intended to read. Karen leaned forward to correct her mistake, but scanned down the list of contents. Her personal screener program had highlighted everything that matched its preprogrammed subset of Karen Langelier’s interests. And near the top of the list appeared the title, “Filamentation in One and a Half Dimensions.”

She pursed her lips, then smiled. “Serendipity, I suppose.”

The author list surprised her. Not content to publish innovative works in only Russian-language journals, Soviet researchers increasingly submitted their most promising work to the prestigious

Letters.

Karen pointed at the article listing and a window flashed open, displaying the contents.

She raised her eyebrows. Published only weeks ago, the Soviet paper presented an elegant yet practical method of constructing one-and-a-half-dimensional strands.

Forgetting her own polymer fiber problem for the moment, she burrowed into the paper and started reading at her “scientific” speed. Lips moving, forehead creased with concentration, Karen began to digest every syllable and equation in the file.

One-and-a-half dimensions.… The concept made her mind reel, but with fascination, like wrestling with a paradox.

Karen allowed her mind to wander. Infinity, possibilities. She knew an embryonic answer floated somewhere at the back of her mind. She could access it with careful stroking, off-center concentration.…

When she had been a young undergraduate, back when the outside world seemed unattached to her reality, Karen would spend hours contemplating irrational numbers. She felt that her understanding gave her some form of control over them. They weren’t infinite where they started—she held one end of the irrational number, the part she could see. A number like pi, simply the ratio of a circle’s circumference to its diameter, starting with 3.14159.… But the rest of the number rolled away from her, an ever-changing sequence infinitely long.

And she could control that number by knowing what it was. She could hold one end of a magical, mystical sequence that lasted forever.

Back then Karen had realized she was different. Not strange, just different—and content to be. She couldn’t relate to the conversations of her dorm mates, the giggling stories, the meaningless concerns. She had a communication problem with them, and she didn’t want to take the time to learn their dialect. Instead, she grew to master her own language, a way of communicating with the precise sciences. Mathematics.

One-and-a-half dimensions …

She closed her eyes now, imagining that she was part of the filament, floating just outside its structure, like an irrational number. The Soviet paper had elegantly shown the full solution in closed form—and now, as Karen drifted there, it all made perfect sense. The answer was inside herself, inside her capabilities, if only she knew how to bring it to the light of day.

The imaginary strand of molecules extended away from her in an endless line. But instead of being a jumbled sequence of nonrepeating numbers, these molecules were ordered, well-posed in a razor sharp line that had no beginning or end. That was the one-dimensional aspect she recognized.

As she imagined herself moving closer to the filament, she wondered what kept the structure from falling apart, from stretching out and collapsing under its own gravitational weight as it hung in front of her. She considered why it wasn’t rigid.

Karen moved around the strand. The molecules stretched down and above, as far as she could see. She approached to touch the apparition and drew suddenly back, her mouth agape.