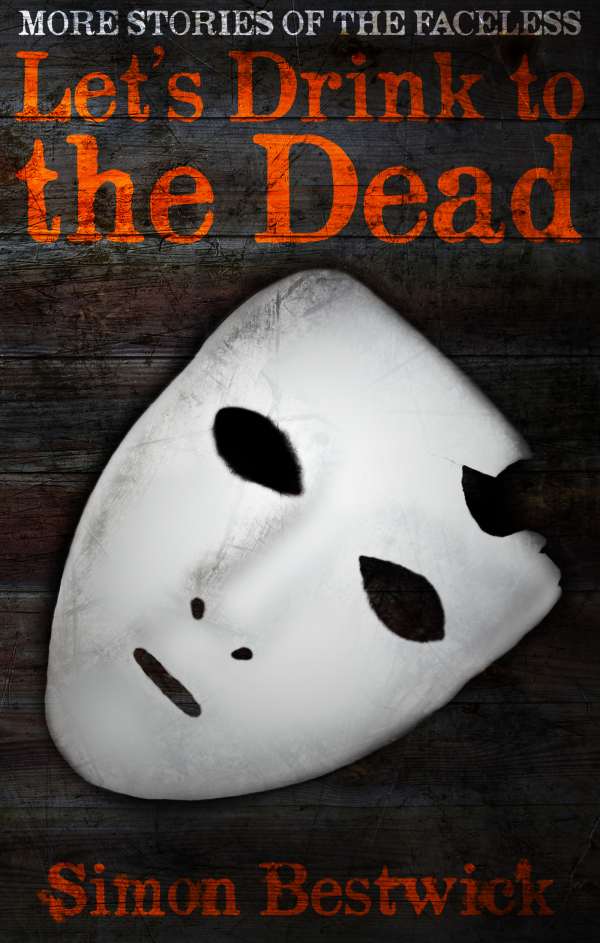

Lets Drink To The Dead

MORE STORIES OF THE FACELESS

LET’S DRINK

TO THE DEAD

SIMON BESTWICK

SOLARIS

First published 2012 by Solaris

an imprint of Rebellion Publishing Ltd,

Riverside House, Osney Mead,

Oxford, OX2 0ES, UK

www.solarisbooks.com

ISBN (EPUB): 978-1-84997-470-7

ISBN (MOBI): 978-1-84997-471-4

Copyright © 2012 Simon Bestwick

Cover Art and Design by Sam Howle

The right of the author to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owners.

This is a work of fiction. All the characters and events portrayed in this book are fictional, and any resemblance to real people or incidents is purely coincidental.

ALSO BY SIMON BESTWICK

Tomes of The Dead: Tide of Souls

Pictures of the Dark

Angels of the Silences

A Hazy Shade of Winter

The Faceless

To Jon Oliver

A good man is hard to find.

THE SIGHT

1985. M

AGGIE’S IN

Downing Street, God’s in his heaven, all’s right with the world.

And Walsh is in the kitchen, in the back of 35 Shackleton Street, in the Lancashire town of Kempforth, filling the kettle and putting it on the hob. He strikes a match and lights the gas, blows the match out, douses it under the cold tap and flicks it in the kitchen bin. Walsh is not a man who takes chances.

The house is silent. He almost feels alone. Vera’s upstairs, but she doesn’t count anymore. He’ll need to find a way of getting shut of her. Should’ve done that first, before her brother, but–

That thought ends for him half-completed as the first bolt of pain tears through his chest and flies down his arm. He has a moment to try and convince himself it isn’t what he knows it is, and then the pain hits again and he fights for breath. He yanks a kitchen drawer out with a crash, pulls one of the chairs over with him as he falls to the lino, and puts his strength into a shout.

Feet thunder on the staircase. Vera stands in the kitchen doorway: nineteen years old, in a Smiths T-shirt and a denim skirt.

Little tart

, he has time to think before the bolt hits again.

“Phone!” he chokes out. Vera half-turns towards the living-room, then turns back to him. “Ambulance.”

At first he thinks she hasn’t understood him. But then when she pulls up one of the surviving chairs and swivels it so it’s got its back to him, then sits astride it, Christine Keeler-style –

little tart –

and props her chin on her arms to watch him as intently as a child watching the progress of a caterpillar, Walsh realises she understands alright. She understands just fine.

T

HE CELLAR IS

damp and cold. There’s a stone or concrete floor, Alan thinks, but he can’t be sure as it’s filmed over with scattered earth. Something digs painfully into his knee; he can’t move.

Over to his right, Mark, the littlest, is crying, or at least as best he can through the ball gag in his mouth. Behind them are Johnny and Sam. Alan is the eldest of the three at fourteen, head and shoulders over the other kids; they’re all between eight and ten.

He knows them all; he’s known them for years. Years of being brought to houses like these for the pleasure of men who lust after children. There’ve been other children, of course; there’ve been other friendships, other alliances, mute compacts of solidarity in places like this when all you can do is alternately feel for the other’s suffering and give thanks it isn’t you. He knows them all and, god help him, he’s an elder among them.

But they’ve never been to this place before. It’s never been quite like this.

Alan’s hands are tied behind his back. His crossed ankles are tied together too, and he’s gagged – like Mark, like all the others. They were made to strip – Daddy Adrian was there, and so were Mr Fitton, and Yolly. Mr Fitton had a knife, but Daddy Adrian just had his smile and that cold tone of voice he used, the one that said

do it or I’ll hurt you

, whatever the actual words were. And so they’d stripped and let Mr Fitton tie them up. Mr Fitton had cooed and patted Alan’s shoulders, fondled them, kneaded them like dough. Which was a bit funny, because Alan sometimes thought Mr Fitton was like a bowl of dough. A big, big bowl of hot greasy dough that fell on top of you from behind and crushed your face into the mattress so that you couldn’t breathe even if you could have got any air into the lungs he’d flattened. A great mound of greasy dough, but with a big metal spike hidden in there that gouged and ripped and tore.

And the cellar is cold and dark but above all the cellar is silent. The only noise is Mark crying – that and a scurrying, scuttling sound from one corner – a rat, most like. There’s no other noise. Sam will be keeping quiet, toughing it out as best he can, trying to find an angle, a way to play it, refusing to admit what they all, deep-down, know: that the angles are all played out and there’s no escape this time. And Johnny, Johnny will be rocking back and forth, trying as always to imagine himself in the world of one of his beloved books, to convince himself this isn’t happening. Until someone – Fitton or Daddy Adrian, Father Joe or the Policeman – comes along to convince him that it is. But that won’t happen again. Something worse than any of them is coming now.

“Shut up,” says Mr Fitton. Alan flinches, the shoulders Mr Fitton kneaded only minutes ago twitching, but it’s not him Mr Fitton means. It’s Mark.

Mark’s sobs choke and stumble, but don’t stop. Mr Fitton’s heavy clomping footsteps sound. His breath’s hoarse and wheezy. Alan flinches again at the hard meaty smack of flesh on flesh. A short, squealing cry from Mark. “I said shut up!”

Mark’s sobs hitch and stutter. He wants to stop, he’s trying to, but he can’t, he’s so scared. Why can’t Mr Fitton see that? Or perhaps he can’t do the things he does if he lets himself see that. The thought surprises Alan. “

I thought I told you to shut up

,” says Mr Fitton in a high, rising voice that sounds like gears grinding, and raises his hand to strike again.

“Mr Fitton, take it easy,” Yolly says. “You don’t want to mark him.”

“Don’t tell me what I want to do,” says Mr Fitton. Alan can see his fat, sweaty face from the corner of his eyes. The quick dark eyes flick up and stare into Alan’s. “What are you looking at?” Mr Fitton spits out, and Alan looks away. Mr Fitton always used to like him, even when he hurt Alan. Said nice things. That he loved Alan, would take him away one of these days. But none of that matters now, does it?

“Shrike dun’t like ’em marked, Mr Fitton,” Yolly says, then claps a hand to his mouth and falls silent, shaking.

Mr Fitton goes still, sweating, swallows hard, and finally his hand drops. “No,” he says. “No, he doesn’t.” He looks back down at Mark. “But you, you little shit, you stop your snivelling.”

Mark whimpers. Mr Fitton breathes through his nose.

“Easy, Mr Fitton.” Yolly comes forward. He’s not that much older than Alan, about Alan’s sister’s age. As far as the likes of Mr Fitton and Daddy Adrian are concerned, he might as well be ancient, though. They used to do the same things to him they do to Alan and the other boys here. Now he’s too old for that, but Mr Fitton lets him help in the butcher’s shop. And now he does to others the things that used to be done to him. Yolly kneels beside Mark. Greasy mop of blonde hair, face spattered with acne. He strokes the boy’s hair and back, like he’s gentling an animal. “Easy. Easy. Hush now.” His hand trails down to stroke Mark’s bum.

Mr Fitton slaps him across the back of the head. “Stop trying to finger him, you dirty little shit. Leave him. Leave ’em all.” His eyes linger on Alan for a regretful moment, then dart away. “They’re the Shrike’s now.”

V

ERA SITS THERE

, watching him.

Several minutes have passed. A slow yellow river of piss flows away from the sodden crotch of Walsh’s fouled corduroys, and she can smell the reek of shit. His head is turned sideways towards her, face pressed against the kitchen floor. His mouth has sagged open – the skin slack and dragged, like his face is a thick liquid that’s been smeared – and his eyes are shut. Aren’t dead people’s eyes supposed to be open?

She’s been listening hard, but she can’t hear him breathe. She’s almost sure he’s dead, but what if he’s not? What if she goes to check for a pulse and he grabs her –

only playing, you little bitch –

or if she calls the ambulance and it turns out he’s alive? She’ll be there waiting for his revenge – helpless, no chance of escape.

So bite the bullet, Vera. Piss or get off the pot.

She clambers off the chair and she goes over to him and feels his throat for a pulse. There’s nothing.

Dead. Dead. The bastard’s dead.

She feels a tight grin chase its tail across her face, and the urge to jump and scream with joy. And then the fear. What now, now the bastard’s dead? She takes deep breaths. There’s still stuff to do.

The kettle’s whistling, a high shrilling note like nails on glass. She gets up, steps over Walsh and the piss – a brief tremor of fright runs through her, like an electric shock rippling up through the soles of her feet, but he stays dead and doesn’t try to grab her – and makes for the stove. At the last second she remembers it’ll be hot and wraps a cloth round her hand before moving the kettle off the hob.

She turns off the gas and looks at the kitchen window. The blinds are down. Always are.

Not having the whole bastard street know our business

, Walsh used to say. With good reason. Vera goes into the living room and draws the curtains.

Now, think fast.

Vera goes upstairs quickly. How long has she got? How long can she leave it before ringing the ambulance and getting away with it?

Tell them you were listening to music. Curled up sleeping. Women’s troubles. They’ll believe that

.

She undresses in the bedroom, folds her clothes away. They’re her good ones, ones she’d wear out tonight. In the bottom drawer are old clothes: cast-offs, stuff that’s only one wash away from the bin. Would be there already if Walsh wasn’t such a cheapskate bastard.

Vera takes a deep breath, pads across the landing, pushes open the door of Walsh’s room. God, the smell of the place; stale, musty. Walsh has –

had

– her cleaning and skivvying for him week-in-week-out, the whole house – her room, her brother’s, scrubbing the loo bowl with an old toothbrush – but not his room. Oh no, no-one gets to see in there. And he doesn’t bother to clean. Hence the rank smell. Even so, she knows. Knows where he keeps his stuff, all his filth. It’s in the loft, in the coal cellar out back, and it’s under his bed.