Let Our Fame Be Great (38 page)

Read Let Our Fame Be Great Online

Authors: Oliver Bullough

22. Russian Cossacks march in Abkhazia, 2008.

23. Hatice Sener, a 75-year-old resident of the Turkish village of Guneykoy. She still speaks Avar, the Dagestani language of the village's founders, as do her neighbours.

24.The Dagestani influence is obvious in Guneykoy.This café has a portrait of Imam Shamil as an old man on the wall.

25. Abubakar Utsiev, the leader of the Chechen Sufis in the Kazakh village of Krasnaya Polyana, stands with his daughter on the bleak steppes.

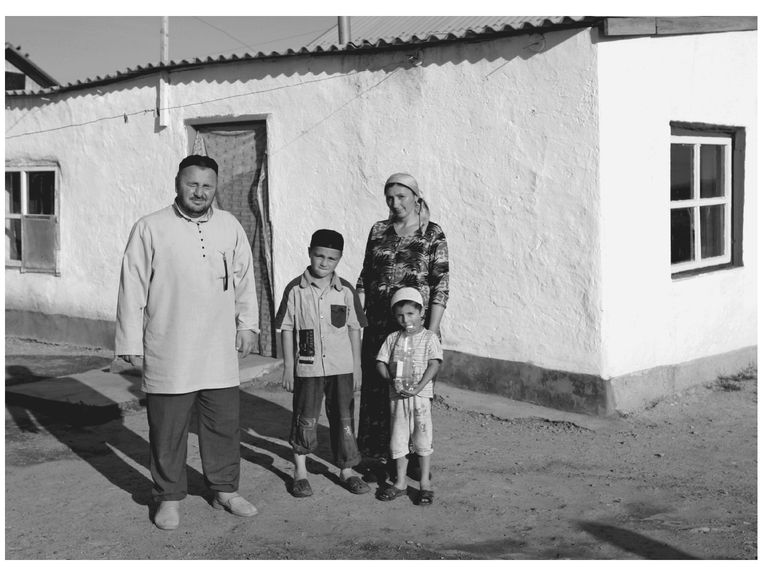

26. Abudadar Zagayev, the only son of the sect's founder,Vis Haji, stands with one of his two wives and their children outside their house.

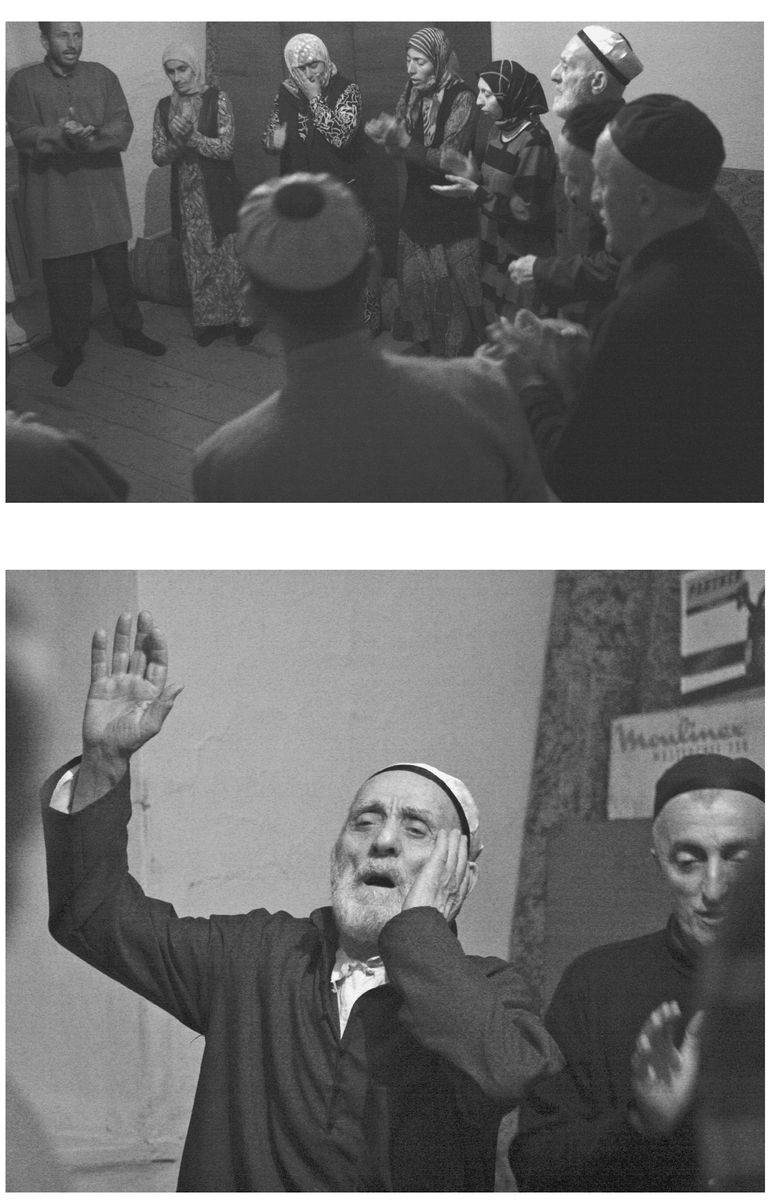

27 and 28. Members of the Sufi sect in Krasnaya Polyana dance their ecstatic zikr, accompanying their chant with drums, âfiddles' and handclaps.

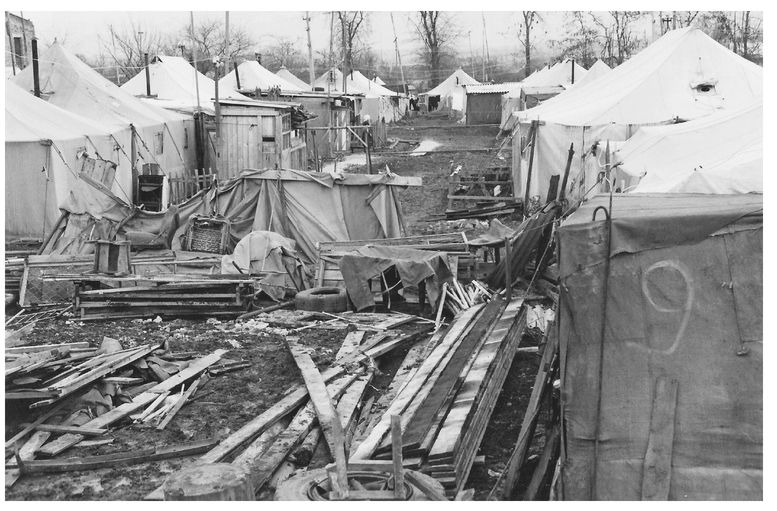

29.Tents in a Chechen refugee camp in Ingushetia, 2004.

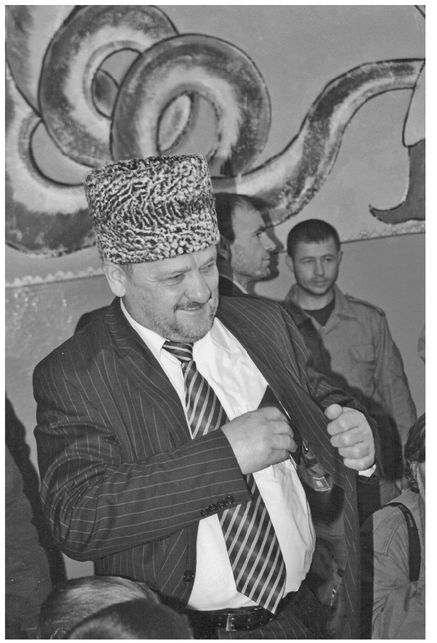

30. Moscow's man in Chechnya, Akhmad Kadyrov, votes in Russian-organized elections in his home village of Tsentoroi, October 2003. He was killed less than a year later.

31. Khasan âDedushka' Bibulatov, the foul-mouthed and hilarious old man who underwent terrible torture at the hands of the Russian army in 1995.

The region's status was unresolved with Russia. Russian officials mentioned Chechnya's independence in negotiations, such as in March, May and September 1992, and accepted its separation from Ingushetia â the Ingush half of Checheno-Ingushetia, which had decided to stay within Russia. However, at the same time, Kremlin representatives tried to undermine Dudayev and his government.

This ambivalence left the door open for unique economic crimes. Dudayev had not abolished the Russian currency, and had pegged bread prices at a nominal one rouble. Since prices were uncontrolled outside Chechnya, a profitable trade in bread sprang up instantly. Chechens also enjoyed the lack of import controls, and bought consumer goods in the Middle East, flew them by chartered aircraft to Grozny, and sold them to residents of the nearby regions of Russia. Grozny became the clearing house for the whole Caucasus. Anything â guns, drugs, televisions, fridges â could be bought there.

Other, more elaborate scams sprang up too. In May 1992, a policeman in Moscow happened to notice a man drop a heavy sack, from which tumbled wads of roubles. The policeman stopped and searched the man and his accomplices, eventually finding more than six million roubles. He had, entirely accidentally, discovered the biggest bank robbery in Russian history. Since the banks in Chechnya were still officially part of the Russian banking system, they could issue promissory notes that would be honoured in Moscow. That meant someone with connections in Grozny could obtain unlimited amounts of cash by just pretending the money had been deposited in Chechnya.

When the fraud was discovered, the Moscow banks were in for another shock. Chechen âpolicemen' had called after the promissory notes were honoured, and asked the banks to hand them over. The banks often had no proof that any money had been given out at all.

For well-connected Chechens, their homeland's legal uncertainty was a goldmine. Khazaliev, however, saw none of this easy money. He was in fact refreshingly upfront about the impact all this political and economic manoeuvring had on his life.

âWe did not know about Dudayev, we were pensioners,' he said with an air of finality when I asked him what he thought of the general's cowboy government. In 1994, after he moved back to Grozny, he was busy getting the house he bought on the edge of the capital ready for his family. It was completed in September that year, and the family enjoyed a huge occasion of feasting and joy.

The Khazaliev family got to enjoy that house for almost exactly three months.

For while the building work was going on, Dudayev and Yeltsin were inching ever closer to violence. A bomb nearly killed Dudayev in the very month that Khazaliev arrived back in his homeland, and a Moscow-backed opposition made regular raids on Grozny from a base near the Russian border. In July, while Khazaliev's house was being repaired and made ready, the Russian government said it might have to intervene if the violence â which it was itself initiating â went on.

In November, after Khazaliev had moved into his new home, the opposition â supplied with tanks by Moscow â attempted to seize Grozny but was forced back, and several of its tanks destroyed.

Yeltsin, humiliated by the defeat of his proxies, threatened to intervene to restore peace. It was a disastrous miscalculation. The Chechens, thousands of whom had been protesting against Dudayev, rallied around their leader, who refused to stand down. It was war.

âWe had to flee Grozny on 17 December,' said Khazaliev. âWe abandoned our house and fled to the village.'

Grozny had become terrifyingly dangerous. Russia's troops â 40,000 strong, but mainly conscripts with little training or idea what they were doing â took weeks to reach Grozny, often stopped by crowds of civilians or by their own disgusted officers. When the Russians finally reached the city, their tanks lacked infantry support and were vulnerable to grenade attacks from apartment blocks lining the streets.

Frustrated by their inability to reach the centre, the artillery and warplanes poured explosives into the city â one observer counted forty-seven explosions within a minute, but was so appalled that he stopped counting before the sixty seconds was up â smashing apartment blocks and the water system, and killing tens of thousands of civilians. One estimate says 27,000 civilians died in the bombardment of Grozny that winter, most of them ethnic Russians who, unlike Khazaliev, had nowhere to go.

Khazaliev crept back to see his house when the fighting had quietened.

âWe went back on 13 February, and found that the soldiers had used our house. Everything was destroyed. My son had a big collection of rare records, and they were all destroyed,' he said.

The son, Ilyas, who had sat in the room with us but stayed quiet up to now, spoke out.

âIf they had stolen the records it would have been better, they could at least have been used somewhere. But they broke everything,' he said. Perhaps emboldened by her son's words, Koka â Khazaliev's wife â spoke up too.

Other books

Bloodlines: Everything That Glitters by Green, Myunique C.

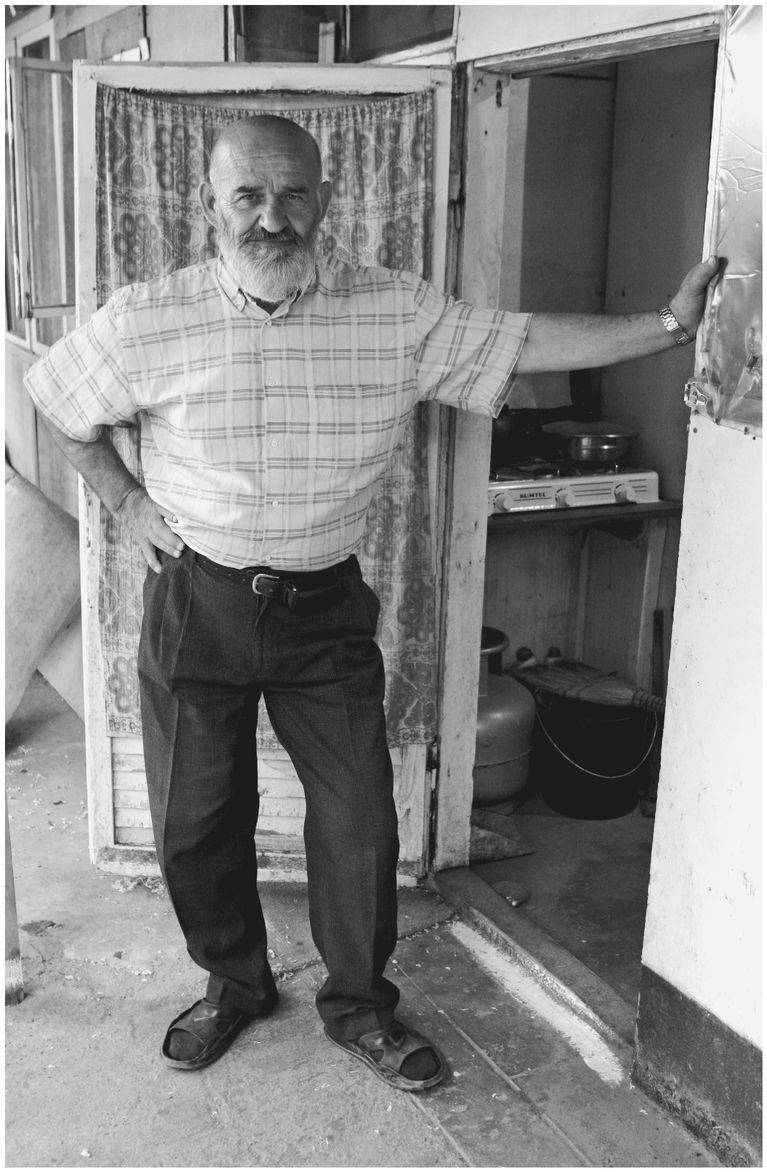

Levi's Blue: A Sexy Southern Romance by M. Leighton

The Pages of the Mind by Jeffe Kennedy

Surrender at Dawn by Laura Griffin

Cuba by Stephen Coonts

A Simple Shaker Murder by Deborah Woodworth

One Was a Soldier by Julia Spencer-Fleming

A Stranger in the Family by Robert Barnard

The Healing by Wanda E. Brunstetter

Dark Torment by Karen Robards