Let Our Fame Be Great (36 page)

Read Let Our Fame Be Great Online

Authors: Oliver Bullough

In August 1991, hardliners rose up against the Soviet Union's reforming leadership. The freedoms of perestroika and glasnost were under threat, but the government in Chechnya hesitated to speak out. Though he was a Chechen, Zavgayev was a good Soviet functionary too. He intended to choose sides when it had become clear who had won. He was in Moscow when the hardliners rebelled, and he sought counsel while he was there. He waited two days before returning to Grozny. When he came back to Chechnya he talked, he thought, he hesitated, and he lost the moment.

Dudayev on the other hand had no hesitation about acting. He called the people out onto the streets to support the democratic movement headed by Boris Yeltsin, who was leading the crowds in Moscow against this attempt to crank back the clock.

Grozny was paralysed by a general strike, and the central squares were thronged by crowds of Chechens revelling in the destruction of communist control.

A fortnight later, they seized the Supreme Soviet and threw a Russian communist out of a window. He was the only casualty of the revolution, which also effectively ended Zavgayev's political career. Yeltsin, who had by this stage defeated the coup in Moscow, put

pressure on Zavgayev to quit and Chechnya's Supreme Soviet dissolved itself.

pressure on Zavgayev to quit and Chechnya's Supreme Soviet dissolved itself.

Dudayev ignored attempts to set up an interim government, and took control himself. A hastily arranged election swept him to power with 90 per cent of the vote, and on 2 November 1991 the new parliament held its first session and declared independence.

It was a momentous time for the Chechen nation, made even better a week later, when Yeltsin's attempt to proclaim a state of emergency in Chechnya failed. Moscow sent 600 troops to Grozny, but they were surrounded by a crowd of civilians, disarmed and sent home. By June 1992, all Moscow's soldiers had left Chechnya. The Chechens were free to decide their own destiny.

In distant Kazakhstan, Aidrus Khazaliev was watching the developments with disbelief. That he could go home to a free Chechnya was a fantasy that he had never even dreamed of. He was retired, and intended to take his whole family to live out the rest of their days in peace.

While Khazaliev planned and schemed to sell his property and gather up his family, Dudayev set his stamp on things. His methods of government involved sweeping plans, which would rarely be fulfilled, and elaborate accusations against Russia. Moscow was indeed working to undermine him, but his constant jibes would have made a working relationship all but impossible to secure even if the Russians had been interested in a stable relationship.

In 1992, for example, he accused a Russian official of putting a price on his head.

âIt started at five million roubles, and now the price has risen to billions. In greenbacks, it is a few million,' he said with ill-concealed relish.

In March that year, Dudayev's opponents within Chechnya sought to storm the television station, and parliament proclaimed an emergency. The television station would prove a regular target; it was blown up later in 1992, as bomb attacks and shootings became standard fare in Chechen life.

1.The Russian army drove the Nogai nomads to their deaths in these marshes, where the Yeya river meets the Azov Sea, in 1783.

2.Three young men hold Circassian and Abkhazian flags at a ceremony by the Bosphorus in Istanbul, on 21 May 2008, commemorating the Circassian genocide.

3. Circassians from all over the Middle East gathered on the beach at the Turkish fishing village of Kefken to mark the Circassian genocide.When night fell, they lit torches and held a memorial procession.

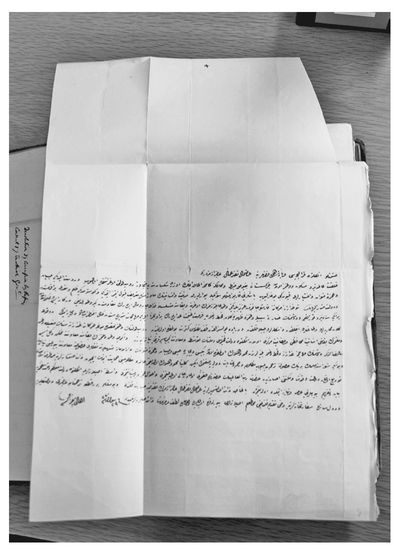

4. A petition signed âThe Circassian nation', addressed to Queen Victoria and dated 9 April 1864, appealing for help against Russia: â⦠there is no act of oppression or cruelty which is beyond the pale of civilisation and humanity, and which defies description, that it has not committed,' the letter said. It almost certainly arrived in London after the final Circassian collapse.

5. Sebahattin Diyner, a Turkish Circassian who spoke at the International Circassian Congress in May 1991, holds a portrait of his grandfather in traditional dress.

6. A Circassian grave in the village of Altikesek in the Uzunyalya region near Kayseri, central Anatolia. It is written in Ottoman Turkish so must date from the first decades of the Circassian presence on the âlong plateau'.

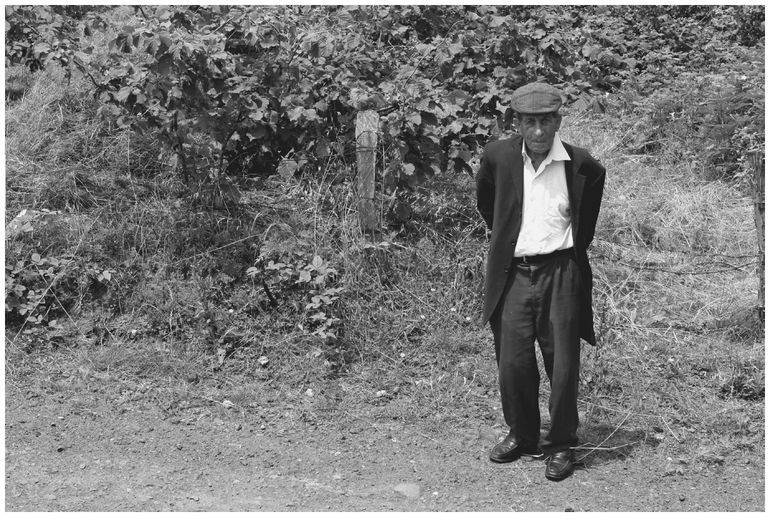

7. Ali Kurt, an eighty-year-old Turk, stands in front of the hazel orchard where he and his father dug up the bones of the Circassians who died in 1864, just outside Akchakale,Turkey.

8. Fragments of bone found in cracks in the rocks below the old ruined fort in Akchakale. I threw them into the sea, towards Circassia.

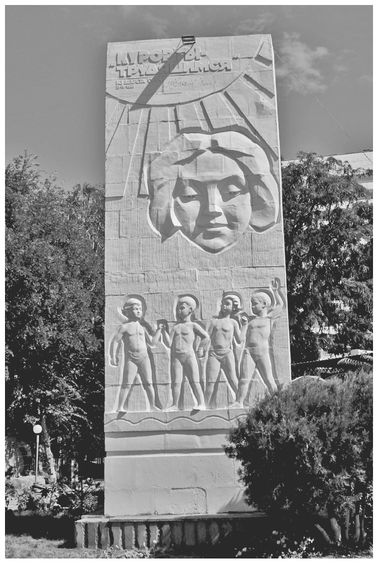

9. A Soviet-era monument commemorates a 1921 decree giving âresorts to the workers', which helped start the transformation of historic Circassia into Russia's holiday coast.

Other books

Haole Wood by DeTarsio, Dee

The Cat’s Eye Shell by Kate Forsyth

Black Run by Antonio Manzini

Partner In Crime by J. A. Jance

Return to Me by Robin Lee Hatcher

Deadlier Than the Pen by Kathy Lynn Emerson

Nine Rarities by Bradbury, Ray, Settles, James

The United States of Vinland: The Landing (The Markland Trilogy) by Taber, Colin

Star Trek The Original Series From History's Shadow by Dayton Ward

The Baker’s Daughter by D. E. Stevenson