Legions of Rome (64 page)

Authors: Stephen Dando-Collins

Discarding their arms and prostrating themselves before the emperor, the bearded Dacian nobles begged Trajan to meet personally with Decebalus, who would, they swore, do whatever Trajan commanded. But, Dio was to write, Trajan was not interested in a meeting with Decebalus. The envoys then asked him at least to send representatives to agree peace terms with the Dacian king, so Trajan sent two of his most senior advisers to Decebalus, Lucius Sura and Praetorian prefect Livianus. [Ibid.]

Decebalus was moving his army west to intercept the Roman invaders as Trajan and the legions crossed the Transylvanian Alps then swung east. Scouts informed the emperor that Decebalus and his army had arrived at Tapae, scene of the bloody

AD

88 battle when Tettius Julianus had been victorious for Rome. When Trajan’s two envoys reached the Dacian camp, Decebalus refused to see them personally, sending subordinates to speak with them. When it was obvious to Sura and Livianus that the Dacian king was only playing for time, they returned to Trajan.

Trajan’s army and the second column now linked up, and pushed east through the mountains. Finding Dacian watchtowers and forts on hilltops overlooking the passes and river valleys, the Romans attacked them and quickly overwhelmed their defenders. At several fortresses Trajan’s troops found artillery and personal weapons taken from the 5th Alaudae Legion in Moesia in

AD

85. Most importantly, to Trajan

and his men, they also recovered the eagle of the destroyed legion. [Dio,

LXVIII

, 9]

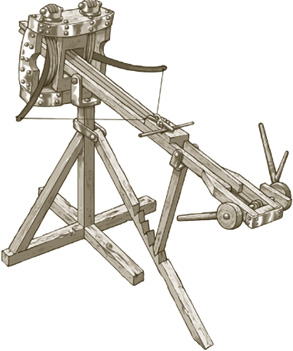

The fifty-five Scorpio catapults, like this one, of the obliterated 5th Alaudae Legion, along with its eagle standard, were recaptured by Trajan in AD 101.

The Roman advance reached Tapae and the sprawling camp of the Dacian army. As Roman catapults of the

cheiroballistra

type were brought up in carts for the assault on the Dacian defenses, Trajan received a message from Germanic tribes of the region which were allied to Rome, beseeching Trajan to “turn back and keep the peace.” [Dio,

LXVIII

, 8] But, despite the fact that autumn had arrived and the days were becoming shorter and colder, Trajan was not going to turn back.

There outside Tapae, in the middle of a thunderstorm, the two armies came together to do battle. Over 200,000 men fought there in the mountain valley at Tapae, in the pouring rain and amid flashes of lightning and crashing thunder. The Dacians did not have the Romans’ organization, but they did have superior numbers and physical superiority, with their scraggy warriors being taller than the average Roman legionary. And at this latest Battle of Tapae, the curved Dacian falx again did great damage to the Romans, as the auxiliaries in the front line took the brunt of the wild enemy charge. The legions also felt the effect of the curved Dacian blades.

So many Romans were wounded in this battle and carried off to the medical attendants working in field dressing stations that the Romans ran out of bandages, and Trajan even had his own linen clothing cut into strips to make bandages for his troops. [Dio,

LXVIII

, 8] But the legions held firm, and won the day. Decebalus’ bloodied army fell back to Sarmizegethusa, leaving large numbers of their countrymen lifeless on the muddy battlefield. Ignoring the atrocious weather, the victorious Roman army stripped the enemy dead of their weapons, valuables and clothing.

Trajan, after honoring his own dead, ordered an altar to be raised on the site of the battle, where funeral rites were to be performed annually in memory of the Romans who had perished there. Despite his victory, Trajan realized that it was pointless to proceed any further. He could see from the deteriorating weather that winter would set in early here in the mountains, and that further military operations would soon become bogged down in mud, snow and ice. The campaign would have to be suspended until the following spring.

In an assembly during which Trajan praised his troops, he doled out rewards to many of them. Trajan’s Column shows auxiliaries bowing to the seated emperor, kissing his hand, and going away bent double with weighty sacks on their backs—filled with captured Dacian gold perhaps, or even salt, which the Dacians mined in this area and which was a valuable trade item. One of the auxiliary units which is known

to have performed well for Trajan in Dacia was the 1st Brittonum Ulpian Cohort, raised by Trajan in Britain in

AD

98. All its surviving members would be given honorable discharges by Trajan thirteen years ahead of their prescribed discharge time—for valiant service in the Dacian Wars, their discharge diplomas record. Perhaps this was the very unit seen on the Column being rewarded in

AD

101.

The Roman army now upped stakes and withdrew via a direct route almost due south to the Danube. According to Trajan’s Column, as the Romans were pulling out of the Dacian interior, Roman prisoners in Dacian hands in the mountains, stripped naked, were being tortured by Dacian women.

Trajan, leaving auxiliary units to spend the winter in forts along the northern side of the river, crossed the Danube at the gorge called the Iron Gate. The emperor and his staff were transported in ships of the Moesian Fleet, which also ferried many troops and their equipment to the southern bank. The boat bridges were also used once again. Opposite Drobeta, the legions built winter camps along the Moesian bank of the Danube, storing away their weapons, not expecting to use them again until the new year. But King Decebalus was not waiting for the Romans to return.

As the winter set in, Decebalus brought together a revitalized coalition of Dacian and Sarmatian fighters. Early in the new year, as the winter weather improved, Decebalus seized the initiative. Without warning, Dacians launched attacks on Roman auxiliary forts on Dacian soil along the lower Danube. At the same time, thousands of Sarmatian cavalry crossed the frozen Danube to the east and entered Moesia behind the backs of the legions.

At the forts in Dacia, fighting desperately, using anything that came to hand as ammunition, auxiliary units were close to being overrun when reinforcements arrived—infantry coming down the river by boat, and cavalry led by Trajan himself which crossed the river by the two boat bridges. A series of carved metopes on the Trajanic monument at Adamclisi tells what happened next. While the infantry fought off the attacks on the Danube forts, Trajan led his cavalry inland, cutting off and surrounding a Dacian baggage train in the hills. In what came to be called the Battle of the Carts, most of the Dacians accompanying the train as escorts or animal handlers were killed, but among the prisoners taken by Trajan were a number of cap-wearing Dacian nobles.

All this time, Trajan was unaware that the Sarmatians had entered Moesia behind him. The legions in Moesia, called to arms by their officers in the last weeks of winter,

marched from their camps and hurried to intercept the Sarmatian invaders in eastern Moesia. The first encounter between the two sides was a brief night skirmish near the village of Nicopole. Then, on a plateau at Adamclisi in the Urluia Valley of today’s Romania, as many as ten legions met some 15,000 Sarmatian cavalry. The battlefield was level ground ideally suited to infantry tactics, and while there are no details of the battle itself, nor of who commanded the Roman army, it is known that the legions slaughtered their mounted opponents that day.

Roman generals had always known that cavalry unsupported by foot soldiers could be beaten by infantry. Here in Moesia, a little over thirty years before, the well under-strength 3rd Gallica Legion had proved that by wiping out 9,000 Roxolani Sarmatian cavalry. The 15,000 Sarmatians who had crossed the Danube on this offensive had not learned any lessons from the earlier brutal defeat, and paid the price now. Very few of the Sarmatian invaders survived the battle. Those that did managed to retreat to the Danube. Even then, with the river ice beginning to break up, a number of heavily armored Sarmatians drowned when the ice gave way under their horses. Not that this had been a cheap victory for the Romans; it has been suggested that as many as 4,000 legionaries died in the hectic Battle of Adamclisi.

Defeated on both sides of the Danube, Dacians and Sarmatians withdrew to the Carpathian mountains. As Trajan returned to the Moesian side of the Danube with his prisoners and congratulated his victorious legions, King Decebalus, at Sarmizegethusa, ordered every possible preparation for the next Roman offensive that he knew must come in the wake of the spring

thaw, and Dacian forces regrouped and completed hurried repairs to mountain fortresses that had been burned during the last Roman campaign. The next stage of the war would be crucial, to both sides.

AD

102

XLI. OVERRUNNING DACIA

The first, false victory

With the spring of

AD

102, Trajan conducted the new year’s lustration ceremony. Trajan’s Column shows him then addressing an assembly of legions and auxiliary units, no doubt hoping to inspire them to victory and make this year’s campaign the last in Dacia.

At Drobeta, the Roman army re-crossed the Danube and marched into the fertile sheep lands of Wallacia. As auxiliary infantry and cavalry scouted ahead, legion work parties cut roads through forests. For this campaign, Trajan again divided his army in two. A flying column of cavalry and light infantry under the command of Lucius Maximus would advance on the Dacian capital from the southwest. At the same time, Trajan would cross the plain of Wallacia then follow the Aluta river to the Red Tower Pass with the legions and the baggage. If all went according to plan, the two columns would link up at Sarmizegethusa in the Orastie Mountains.

One mountain stronghold after another was stormed by Trajan’s legions as they pushed on across the Transylvanian Alps. Pliny the Younger, the noted Roman author, and a consul in

AD

100, describes Roman marching camps “clinging to sheer precipices” during this campaign. [Pliny,

VIII

, 4] Trajan’s Column shows the Roman army assaulting a stone-walled citadel. On poles outside the walls sit severed heads of bearded men—either those of captured Roman auxiliaries or of Dacians who had wanted to surrender. The Column next shows auxiliaries setting fire to wooden buildings inside the captured Dacian citadel, then moving on.

Trajan himself followed close behind the advance, and in the Column’s narrative he was at this point crossing a wooden bridge placed across a ravine. As the Roman advance guard erected another marching camp near a Dacian town which had several round shrines in the background, Dacians assembled behind their standards in the hills. The main Roman column arrived on the scene with legion musicians playing

their trumpets and horns. The baggage train lumbered in, its oxcarts laden with equipment. From this camp, Trajan directed the next stage of the operation.

Now Dacian forces descended from the heights and attacked advancing Roman cavalry and light infantry. Following a fierce struggle, the bloodied Dacians withdrew into the forests. Another day’s advance, another marching camp thrown up. Artillery was brought forward for an assault on the next Dacian hilltop fortress on the road to Sarmizegethusa.

To save time, wooden hurdles, usually employed to cover enemy trenches, were used to create protection for the Roman catapults’ firing positions, for the Dacians possessed excellent archers. Trajan’s Column shows crates of catapult ammunition opened and ready for use, revealing catapult balls packed neatly inside. [Vitr.,

X

.3] Small balls were for anti-personnel use; larger ones were fired at emplacements.

On the Column, eastern archers with conical helmets and barefoot slingers without armor are shown launching a rain of missiles against the walls of the Dacian fortress. Behind them, the catapults let fly their balls. Between them, archers, slingers and catapults would have cleared one section of the wall of defenders. Dacians raising their heads above the parapet at that point would have invited death. Waiting Roman infantry rushed forward, clambered over outer palisades, hurdled ditches, then dashed for the wall with assault ladders.

Trajan’s Column shows that, to try to drive the Romans back from the wall, Dacian defenders poured out of a fortress gate to the attack. But Trajan had been expecting this and thousands of auxiliaries surged toward the Dacians, who were slaughtered in the open; only a few escaped, fleeing into the forest. After that the fortress was swiftly taken. Relentlessly, the Roman army moved on. Dacians cut down trees to slow the Roman advance up the valley, and laid ambushes in expectation of catching legionaries as they tried to clear the roadblocks. But Trajan merely diverted via another route through the forest, with his advance guard cutting a road through the trees.

As the advance guard emerged into open country from the forest, a large Dacian force fell on them. Roman auxiliaries fought off the Dacians, who fell back to another hilltop fortress. Trajan assaulted the fortress, where a wounded Dacian noble—perhaps the fortress commander or one of Decebalus’ generals—is shown, on the Column, in the arms of subordinates at the wooden palisade line.