Legions of Rome (34 page)

Authors: Stephen Dando-Collins

When Diocletian became co-emperor in

AD

285, he disbanded the Praetorian and City Guards, replacing them as Rome’s guardians with two legions from the Balkans, with a total strength of 10,000 men who earned the same pay as other legionaries. Diocletian had taken the title Jove, and his co-emperor Maximianus the title Hercules, and their two new city legions became the Jovia and the Herculiana. Both units took the eagle as their emblem, one with wings raised, the other with wings lowered.

Maxentius, emperor from

AD

306, reformed the Praetorian Guard, sending the Jovia and Herculiana legions to the frontiers. Maxentius’ Praetorian Guard fought for him against his brother-in-law Constantine the Great at the

AD

312 Battle of the Milvian Bridge just outside Rome. After winning the battle, Constantine abolished the Praetorian Guard; its surviving members were not permitted within 100 miles (160 kilometers) of Rome. Constantine left Rome without a dedicated military force; the Praetorian Guard was never reformed. Praetorian prefects, who in the past had wielded enormous power, continued to be appointed, but merely as financial administrators.

THE IMPERIAL SINGULARIAN HORSE

EQUITUM SINGULARIUM AUGUSTI

EMBLEM:

Scorpion.

HEADQUARTERS:

Castra Equitum Singularium, Rome.

FOUNDED:

AD 69 by Vitellius. First saw action for Vespasian, AD 70.

GRANTED AUGUSTI TITLE:

By Trajan.

XV. THE EMPERORS’ HOUSEHOLD CAVALRY

The imperial household cavalry, the mounted equivalent of the Praetorian Guard

.

This elite unit served as the mounted equivalent of the Praetorian Guard from the first century to the fourth century. The original

Equitum singularium

, or Singularian Horse, was an elite auxiliary cavalry unit created in the summer of

AD

69 by the emperor Vitellius to replace the Praetorian Horse when he disbanded Otho’s Praetorian Guard.

Hand-picked German cavalrymen, these inaugural Singularians surrendered to Vespasian’s forces in central Italy in December

AD

69. The unit’s first service for Vespasian was in early

AD

70, against Civilis’ rebels on the Rhine. Tacitus wrote that after Vespasian’s general Cerialis and his spearhead arrived on the Rhine, “they were joined by the Singularian Horse, which had been raised some time before by Vitellius and had afterward gone over to the side of Vespasian.” [Tac.,

H

,

IV

, 70]

The first commander of the Singularian Horse was Briganticus, a Batavian and nephew of Civilis. Briganticus died while fighting his uncle’s forces on the Lower Rhine in the late summer of

AD

70. Thirty years later, under Trajan, the unit gained the honorific

Augusti

, signifying that it served the emperor. The unit was thought to use a hexagonal, German-style shield bearing the motif of four scorpions. [Warry,

WCW

] The scorpion emblem possibly related to the Greek legend where a scorpion caused the horses of the Sun to bolt when the Sun’s chariot was being driven for a day by the inexperienced youth Phaeton.

In

AD

70 the unit consisted of two wings, each of 500 men. Trajan increased the Singularians to 1,000 men. Septimius Severus doubled the unit again in

AD

193 to 2,000 troopers. The Singularian Horse barracks and stables complex, the

Castra equitum singularium

, stood on the capital’s eastern outskirts, beyond the old city walls and below the Esquiline Hill. In republican times Roman horsemen had exercised in the Esquiline Fields. The Singularians’

AD

193 expansion saw them with two adjacent barracks, “old fort” and “new fort.”

The unit was disbanded in

AD

312 by Constantine the Great, for siding with Maxentius and opposing him. Constantine also had the Singularian barracks leveled and the unit’s graveyard demolished.

XVI. THE IMPERIAL BODYGUARD

The German Guard and its successors

Confused with the separate Praetorian Guard by some modern authors, the

Germani Corporis Custodes

, literally the German Body Guard, served as the personal bodyguard of Rome’s first seven emperors. Variously called “the Bodyguard,” “the German Cohorts,” “the Imperial Guard” and “the German Guard” in classical and later historical texts, this was an elite infantry unit made up of hand-picked German auxiliaries. According to Josephus, it was a unit of legion strength. [Jos.,

JA

, 19, 1, 15]

On their gravestones, several men of the German Guard referred to themselves as

Caesaris Augusti corporis custos

, to let the world know they had served as the emperor’s bodyguard, but the

Augusti

title, carried by the Singularian Horse from the second century, was never officially applied to the German Guard. [Speid., 1]

That the German guardsmen were primarily foot soldiers was made clear by Tacitus and Suetonius, speaking of their “cohorts,” a designation that only applied

to infantry or equitata units. [Tac.,

H

,

III

, 69; Suet.,

II

, 49] Josephus wrote, “These Germans were Gaius’ [Caligula’s] guard, and carried the name of the country whence they were chosen, and composed the Celtic legion.” [Jos.,

JA

, 19, 1, 15] Arrian also described Germans serving in the Roman army as “Celts,” in his case referring to men of the 1st Germanorum miliariae equitata cohort. [Arr.,

EAA

, 2] Being the equivalent of a legion, like all legions the German Guard probably included a mounted squadron, explaining why the tombstone of a member of the unit accorded him the rank of decurion.

Suetonius says that Augustus only allowed three cohorts of the German Guard to be on duty at Rome at any one time; the other cohorts, he said, were quartered on rotation in towns near Rome. [Suet.,

II

, 49] In

AD

69, the German Guard was using the Hall of Liberty as their quarters at Rome. [Tac.,

H

,

I

, 31] Previously, they had used a fort west of the Tiber, just inside the Servian Wall, which may have been demolished by Galba in

AD

68. [Speid., 6, 7] German Guard troops were not Roman citizens. They wore breeches, were tall, muscular, and bearded, and their armaments were the long German spear, a dagger, and a long sword with a blunt, rounded end. Their shield was large, flat and oval. They were commanded by an officer of prefect rank; Caligula’s German Guard prefect was a former gladiator.

In

AD

41, men of the German Guard hailed Claudius emperor after the assassination of Caligula, and this led to Claudius taking the throne. During the war of succession, the German Guard was dissolved by Galba but reformed by Otho, and was with Otho at Brixium when he committed suicide. Serving Vitellius, three cohorts of the German Guard stormed and burned the Capitol in December

AD

69, executing Vespasian’s brother Sabinus, before fighting to the death in the December 20 Battle for Rome. Vespasian abolished the German Guard, making the Praetorians his bodyguard.

Later emperors created a variety of bodyguard units. In

c

.

AD

350, the personal bodyguard of Constantius II was provided by the

Protectores Domestici

, or Household Protectors. The future historian Ammianus Marcellinus served as a junior officer with this unit, which was based at Mediolanum (Milan) in Italy, Constantius’ imperial capital.

A silver plate of

AD

388 found at Badojoz in Spain depicts the Spanish-born emperor Theodosius I with his heirs Valentian II and Ariadius, plus a bodyguard from two different units. The tall, clean-shaven spearmen of the bodyguard are shown

carrying very large oval shields and lances, and wearing boots and neck torques. One of the two shield designs of the soldiers of the bodyguard appears on the Notitia Dignitatum thirty years later, and is of the Lanciarii Galliciani Honoriani, or the Honorary Gallaecian Lancers, a Spanish unit which was attached to the central command of the Master of Foot.

According to the Notitia Dignitatum, by early in the fifth century the imperial bodyguards of both the emperors of the east and west were the Domestici Pedites and Domestici Equites, the Household Foot and Household Cavalry.

XVII. LEGIONS OF THE LATE EMPIRE

Numerous new legions were raised by various emperors from the third century. Some of these were split off from existing legions, others were new creations and took the names of the emperors who founded them. Little is known about any of these Late Empire units.

The emperor Diocletian, during his reign (

AD

285–305), significantly reorganized the Roman military and increased the pay of the troops in an attempt to keep pace with the galloping inflation of the era. Successor Constantine the Great took Diocletian’s reforms even further, and by the end of the fourth century the Roman army was made up, on paper at least, of 132 legions and hundreds of auxiliary and allied numeri units. [Gibb.,

XVII

]

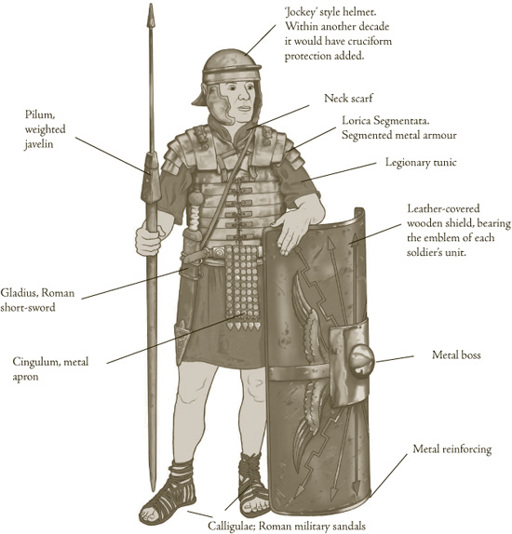

ROMAN LEGIONARY AD 75

The legions listed in the Notitia Dignitatum at the end of the fourth century were Palatine and Comitatense legions. The former, just two dozen of them, were the elite legions, whose men were paid more than other legionaries and enjoyed other privileges. In the early years of Constantine’s reign these legions, slimmed down from the size they had enjoyed even during Diocletian’s reign, were no longer housed in their own permanent camps throughout the empire. Withdrawn from the frontiers, they were billeted in the major cities of the provinces, at those cities’ expense, and on

unfriendly terms with the local populations, becoming idle and undisciplined. This “innovation,” according to Gibbon, “prepared the ruin of the empire.” [Ibid.]