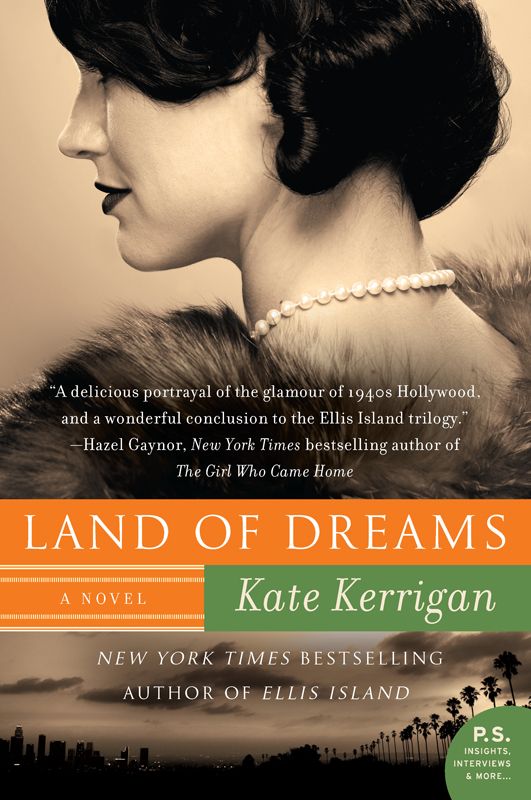

Land of Dreams: A Novel

Read Land of Dreams: A Novel Online

Authors: Kate Kerrigan

For Leo and Tommo

C

ONTENTS

Part One: Fire Island, Long Island Shore, New York 1942

Part Two: Chateau Marmont, Hollywood 1942

P.S. Insights, Interviews & More . . .*

Praise for Kate Kerrigan and the Ellis Island Trilogy

It was a mysterious day on Fire Island.

The visitors of high summer were gone and the beach at the end of the walkway to our cabin was entirely empty. It was hard to believe that this thin strip of barrier land off the Long Island shore was less than two hours’ drive from the teeming chaos of New York City, followed by a short ferry ride. Although the air was still warm and the sky a sharp blue, I could sense autumn in the swell of the sea. There was no wind to speak of and the white sand along the edge of the beach was as soft and warm as a wool carpet—yet the waves seemed uncharacteristically high. They lumbered toward the shoreline like an advancing battalion of old, slow soldiers. The gray hills kept coming—bloated by an invisible wind, rising into fat mounds, line after line of them until, with a gasp of shock, they shuddered into pathetic sandy bubbles on the shoreline.

I sat and watched them for a while, contemplating their rhythmic symmetry, trying to picture in my mind’s eye how I might paint them, when I was interrupted by Tom, who had been playing in the dunes behind me. A brown bobtail rabbit rushed past my eyeline and in its pursuit was my raven-haired seven-year-old son.

“Damn!” he shouted.

“Don’t say ‘damn,’ I said in the admonishing tone I reserved exclusively for him. Tom was so different from his older brother. Leo was serious and beautiful, but remained something of a mystery to me. Tom was an open book—stocky and lively and inquisitive. He looked at me, then pursed his lips and shook his head in frustration as if holding the bad word inside and bouncing it around his head. I struggled to keep myself from laughing. His dark curls were sun-dyed red at their tips after a hot summer at the beach, his cheeky round face littered with freckles. A true child of nature, he was barefoot and dressed in just a pair of torn trousers.

He’s entirely unsuited for the civilized world

, I thought,

just like me!

I was flooded with love.

“Gotcha!”

Briefly cornered at the shoreline, the rabbit had stopped for a moment to contemplate its options. Which was the more dangerous: chancing a few hops into the sea and risk drowning, or putting himself in the hands of the raven-haired bounder who had doggedly been pursuing him for weeks? While the rabbit made up its mind, my son suddenly threw himself on the creature in an alarmingly quick and somewhat feral movement.

“Mammy! Help me!” he called as the fluffy bundle flattened itself underneath him, threatening to wriggle out from under his torso.

I ran across to him in three long strides, my feet struggling to grip the sand.

“Don’t move, Tom,” I said, as I slid my hands under my son’s chest. I quickly took the bunny’s two ankles in one hand, just as it was burrowing an easy escape route through the soft ground.

“Now get up slowly,

slowly now

. . . ,” I told Tom. “Back there now, easy, easy.”

As my son moved his body aside, lifting each limb individually with comic stealth, I scooped up the bunny with my free hand and held it firmly to my chest. The poor creature was quivering with fear, its ears flattened, playing dead in my arms—as if pretending to be no more than a tan-colored fur muff that I might forget about and cast aside.

“Come on,” I said, “let’s go back to the house and get some breakfast.”

As we walked toward our cabin, Tom swung his arms like a soldier; he was strutting with pride at having finally caught the rabbit he’d been chasing these past few weeks. He nodded his head up and down the deserted beach, as if acknowledging the cheers of an invisible audience.

When we passed the sand dunes at the back of our house I crouched down so that Tom and I were eye to eye. The rabbit was a hot, silent bundle in my lap, a terrified prisoner.

“Do you want to stroke it?” I asked.

Tom put his small slim fingers into a bunch and stroked the bunny’s forehead; its eyes half opened in an all-forgiving ecstasy.

I looked at my son’s face and it was pure joy, untainted with pain, unsullied by corruption—full of childish expectation that this feeling of total happiness was his right and would last forever. He had what he wanted now, had finally captured what he had been chasing.

“Thanks, Mam,” he said, “for helping me catch it.”

My heart opened up and snatched the compliment. The more he grew away from me, the greedier I became for the affection of my miniature man—my own maneen, as we called such sons back home in Ireland.

“He’s so soft, Mammy, I love him. I’m going to love him forever.”

A dark cloud moved over the blue sky ahead, and fat drops of rain fell into the sand beside us. Tom put his hand on the rabbit’s head as a makeshift hat, then turned his face skyward in an uncertain grimace, opening his mouth wide to catch the raindrops.

I wanted, in that moment, to indulge him, to give myself over to the mawkish instincts of my love for my baby son, but I knew I had to do the right thing.

I lifted the rabbit from my lap and put it on the sand in front of us. It sat quietly for a moment, unsure that it was really being let go.

“What are you doing?” Tom asked, his hands reaching out for the animal.

I put my arms around his waist and held on to him, saying, “The rabbit doesn’t belong with us, Tom. It’s wild—it needs to go home to its own mammy. It needs to be free.”

“But I love him,” he said, his face collapsing.

“I know you do,” I said, “but the rabbit won’t be happy living with us, and you want him to be happy, don’t you?”

He looked at me uncertainly, struggling to weigh up the rabbit’s well-being against his own desires.

“We have to let him go,” I said, as the animal leaped forward and disappeared into the dunes in one square hop.

Tom broke away and ran toward the house sobbing. “I hate you! I hate you!” he cried.

I followed behind him, regretting that life lessons were always so hard-learned, and wondering if I should have let him cherish his dream a little longer.

Fire Island,

Long Island Shore,

New York

1942

I stood back and looked at the painting. It was a four-foot-by-six-foot landscape of the dunes in muted gray colors, a barely discernible figure approaching from the distance—little more than a smear—representing the mereness of humans against the magnitude of nature.

It wasn’t my best work. It was a commission from a wealthy industrialist with Irish parentage, who was spending his money for the sentimentality of investing in an Irish artist, more than for loving the art itself, so I wasn’t going to agonize over it for days.

I rubbed my hands together, before poking at the left-hand corner to check that it was dry enough to transport. The studio was cold and, despite having run the gas heater for an hour before going in to start work, the air had the bite of ice to it.

It was late October, but already vague icy patterns were forming on the inside of the small glass windows.

“You’re crazy staying out there all winter,” Hilla, my art benefactor, had said. “You’ll freeze. Think of the children,” she went on, as a last desperate attempt to talk me into going back to Manhattan and the round of society functions and art-world parties she was always dragging me along to.

I smiled when she said it. Hilla didn’t give a damn about my physical well-being; or, indeed, my children. Hilla just cared about art—Non-Objective Painting, to be exact—but she liked me well enough to make an exception for my Abstract Impressionist landscapes. Mostly she missed me as a friend—and that was one reason why I didn’t want to return to the city. I was tired of the endless round of “doing” and being with other people that, as my benefactor, she dragged me into.

As a young woman I had relished and craved the social buzz of life in Manhattan. The glamour and freedom there had helped me escape the cloying Catholicism of my poor Irish upbringing—I thought of New York as my “City of Hope.”

At forty-two, and after eight years living back here full time, the novelty of its social whirl had worn off and I longed only for solitude and quiet in which to paint.

“You’ll starve,” she finally conceded, but we both knew that wasn’t true. My work was popular enough and I had already been paraded about New York society, had fraternized with her friends the Guggenheims and their like, as “Hilla’s new find, darling: Eileen Hogan—she’s Irish.”

“Irish? An Irish artist? How unusual!”

How collectible, it turned out. German Abstract Impressionism was old hat at this stage. Irish Abstract art? As far as I could gather, we were few and far between. I liked to think that my work was popular because it was beautiful, serene and dense with color and meaning. I had started painting as a hobby to please myself, in an effort to recapture something of what I missed of Ireland. I was happy with my life in New York, the vibrancy, the people, the anonymity—but I missed the beauty of my homeland. Postcards and photographs could not express the mixed emotions I felt in memorizing what I missed of the green fields and the crisp air; the soft mist of an autumn morning as it seemed to seep up from the purple bog. So I spread the images as they appeared in my head onto canvas with a paintbrush, daubing dots and lines of color, trying to recapture my past. I tried to believe it was the work itself that earned my success, but there was an element of novelty around me too. Collectors coveted the unusual and I was not only an Irish Abstract painter living in New York—but a female to boot. There were two or three notable Irish female artists that I knew of because of Hilla’s contacts in Europe, who were constantly on the lookout: the furniture designer Eileen Gray, a woman called Evie who worked in stained glass and Mainie Jellett—a “fine painter: an original artist,” whom Hilla kept threatening to bring over to New York and give my crown to. While I had no intention of giving in to Hilla, I understood that much of her bullying had to do with fear.