King George (12 page)

Authors: Steve Sheinkin

“T

he news of Burgoyne's surrender lifted us up to the stars,” wrote John Adams. Wait till Ben Franklin finds out.

he news of Burgoyne's surrender lifted us up to the stars,” wrote John Adams. Wait till Ben Franklin finds out.

In early December, a carriage pulled up to Franklin's house in France. Franklin had been hearing rumors that General Howe had captured his hometown of Philadelphia. Franklin rushed up to the messenger:

Franklin:

Sir, is Philadelphia taken?

Sir, is Philadelphia taken?

Messenger:

It is, sir. But sir, I have greater news than that. General Burgoyne and his whole army are prisoners of war!

It is, sir. But sir, I have greater news than that. General Burgoyne and his whole army are prisoners of war!

Burgoyne, a prisoner of war! This changed everything. After months and months of avoiding Franklin, France's King Louis and his officials finally agreed to work out a treaty with the United States.

Franklin prepared for his big meeting with King Louis by hiring

the best wig maker in Paris (no one showed up to see the king without a nice wig). Unfortunately, the wig maker made Franklin a wig that didn't fit. A Paris newspaper reported the scene:

the best wig maker in Paris (no one showed up to see the king without a nice wig). Unfortunately, the wig maker made Franklin a wig that didn't fit. A Paris newspaper reported the scene:

Franklin:

Perhaps your wig is too small?

Wig maker:

No, your head, sir, is too big!

Perhaps your wig is too small?

Wig maker:

No, your head, sir, is too big!

The newspaper reporter added his own comment: “It is true that Franklin does have a fat head. But it is a great head.”

Anyway, Franklin decided to go to the palace in his plain brown suit and his plain bald head. The king's servants were horrified (at first, they didn't even want to let him into the palace). Everyone waited, too scared to breathe, as Franklin boldly stepped up to meet King Louis. Luckily, Louis didn't seem to care about Franklin's head one way or the other. He simply looked at Franklin and said:

“Assure Congress of my friendship.

I hope this will be for the good of the two nations.”

And that was that. Franklin's mission was accomplished.

King Louis XVI

N

ow you can see why the battle of Saratoga is called the “turning point” of the American Revolution. The Continental army had won its biggest victory yet over the British. And this victory convinced France, one of the most powerful nations in the world, to join forces with the United States.

ow you can see why the battle of Saratoga is called the “turning point” of the American Revolution. The Continental army had won its biggest victory yet over the British. And this victory convinced France, one of the most powerful nations in the world, to join forces with the United States.

The members of Congress were so excited, they gave General Gates a special medal to celebrate the battle of Saratoga. And at night, members and their wives did a new dance called “the Burgoyne surrender.”

Not everyone was dancing, though. Stuck in a hospital bed in Albany, Benedict Arnold was recovering very slowly from his wound. Army surgeon James Thacher reported: “Last night I watched with the celebrated General Arnold, whose leg was badly fractured by a musket-ball while in the engagement with the enemy ⦠. . He is very peevish, and impatient under his misfortunes.”

It wasn't just the pain in Arnold's leg that was bothering him. He was tortured by the fact that Gates was getting the glory he felt belonged to him.

We'll be hearing more from Benedict Arnold.

In 1777, Joseph Plumb Martin, now seventeen, decided to rejoin the Continental army. He agreed to serve until the end of the war. “The general opinion of the people was that the war would not continue three years longer,” Martin said.

Don't tell Joseph, but the American Revolution was going to last six more years.

S

ure, the Americans had won that great Saratoga victory. But the British were still determined to smash this revolution. And they still had thousands of soldiers in the United States. In fact, they had thousands of soldiers in the

capital

of the United States. In September 1777 (while Burgoyne was fighting in New York) the main British army, under the command of General William Howe, captured the city of Philadelphia. Members of Congress packed very quickly and escaped to York, Pennsylvania.

ure, the Americans had won that great Saratoga victory. But the British were still determined to smash this revolution. And they still had thousands of soldiers in the United States. In fact, they had thousands of soldiers in the

capital

of the United States. In September 1777 (while Burgoyne was fighting in New York) the main British army, under the command of General William Howe, captured the city of Philadelphia. Members of Congress packed very quickly and escaped to York, Pennsylvania.

Now the winter of 1777 approached, and George Washington was facing the same old maddening problems: lack of soldiers, lack of food, lack of clothing ⦠“The army was now not only starved but naked,” said Joseph Plumb Martin. “The greatest part were not only shirtless and barefoot, but destitute of all other clothing, especially blankets.”

No, the Americans were nowhere near winning this war.

W

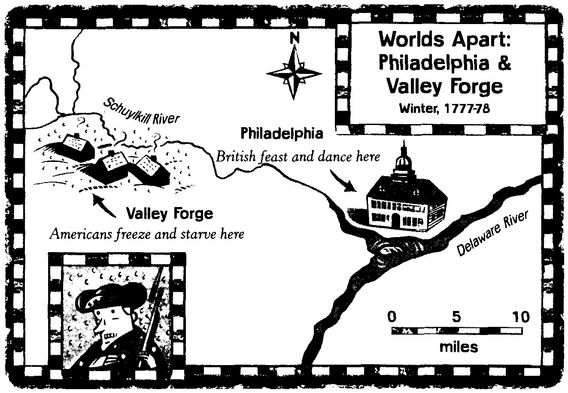

ashington decided to keep his army close to Philadelphia that winter. He wanted to make sure General Howe didn't make any sudden, unexpected moves. So in December 1777, 11,000 American soldiers marched toward a place called Valley Forge, about twenty miles west of Philadelphia.

ashington decided to keep his army close to Philadelphia that winter. He wanted to make sure General Howe didn't make any sudden, unexpected moves. So in December 1777, 11,000 American soldiers marched toward a place called Valley Forge, about twenty miles west of Philadelphia.

Some of the men were so exhausted by the march, they leaned on their guns and slept standing up. Others were more worried about their aching feet. Dr. James Thacher reported, “It was not uncommon to track the march of the men over ice and frozen ground, by the blood from their naked feet.”

There wasn't much at Valley Forgeâjust some bare trees and windy hills covered with frost and dead grass. Since some kind of shelter was needed, Washington ordered the men to build log cabins. Twelve soldiers would live in each cabin. The men who knew how to build log cabins finished theirs in two days. Then they helped the city boys, who had no idea how to build a house out of logs.

Washington knew his army was facing a dangerously long, hard winter. Martha Washington, who came to stay at Valley Forge, could see the concern on her husband's face:

“The General is well, but much worn with fatigue and anxiety. I never knew him to be so anxious as now.”

Martha and the other women in camp knitted socks and shirts as fast as they could. And the men badly needed the clothing. Some had nothing but ragged summer clothes, and they could be seen dashing from hut to hut wrapped in blankets. When soldiers were on duty, they stood on their hats to keep their bare feet from freezing solid in the snow. When they weren't on duty, they shivered in their cabins, coughing from the smoke from their fires and trying to ignore the hunger pains in their bellies.

Martha Washington

Dr. Albigence Waldo described life at Valley Forge in a few harsh statements:

“I am sickâfatigueânasty clothesânasty cookeryâvomit half my timeâsmoked out of my sensesâthe Devil's in itâI can't endure itâWhy are we sent here to starve and freeze?”

The only one who had anything nice to say about Valley Forge was a young soldier named Richard Wheeler. “We are very comfortable and are living on the fat of the land,” wrote Richard to his mother. Richard wasn't quite telling the truthâhe just didn't want his mom to worry.

Albigence Waldo

And she would have worried had she known that there was so little food at Valley Forge that horses were starving to death and dropping dead in the middle of camp. Men, also starving, were too weak to bury the heavy horses. “The carcasses of dead horses are lying in and near the camp,” complained Washington. The rotting horse bodies stank up the camp and helped spread disease among the weakened soldiers.

An increasingly desperate and angry George Washington watched more than 2, 500 soldiers die from cold, hunger, and disease at Valley

Forge. He was furious with Congress for not doing more to supply the army. And he knew that if the British chose this moment to attack, his army would be ruined.

Forge. He was furious with Congress for not doing more to supply the army. And he knew that if the British chose this moment to attack, his army would be ruined.

L

uckily for the American Revolution, General William Howe preferred to spend the winter indoors.

uckily for the American Revolution, General William Howe preferred to spend the winter indoors.

Howe and the other top British officers sat by blazing fires, playing cards and sipping wine. The British had taken over all the finest houses in town, including Ben Franklin's three-story brick mansion. So Ben's daughter Sarah had to find a new place to live. “I shall never forget or forgive them for turning me out of house and home in the middle of winter,” Sarah wrote to her father.

At least they wouldn't be able to steal Ben's books. “Your library we sent out of town, well packed in boxes,” Sarah added.

One of the British officers enjoying the Franklin mansion was a twenty-eight-year-old captain named John André. A talented artist, musician, and writer, André turned a local warehouse into a theater and put on thirteen different plays that winter. In his free time, he visited the homes of young American women, entertaining them by playing flute and reciting poetry.

André was a frequent guest at the Shippen home, where a beautiful and intelligent seventeen-year-old named Peggy Shippen lived with her wealthy family. John and Peggy sat in the living room for hours at a time, chatting and drinking tea (sometimes fifteen cups per visit). John took Peggy out to dinners and balls and on sleigh rides.

We don't know what they were talking about all this time. We do know that they soon started working together on a plan they hoped would destroy the American Revolution. Remember their names.

B

ack in Valley Forge, life was slowly beginning to improve. Spring brought warmer weather, and wagons full of food began rolling into the American camp. Soldiers set up their own little theater and put on playsâGeorge and Martha Washington were always in the audience.

ack in Valley Forge, life was slowly beginning to improve. Spring brought warmer weather, and wagons full of food began rolling into the American camp. Soldiers set up their own little theater and put on playsâGeorge and Martha Washington were always in the audience.

George also relaxed by tossing a ball back and forth with his officers. While Washington was a humble man, he was always proud of his strong right arm. “I have several times heard him say,” said a friend, “that he never met any man who could throw to so great a distance as himself.”

Another welcome sight at Valley Forge was a short, loud German fellow by the name of Friedrich von Steuben. Steuben impressed the Americans by telling them he had been a general in Germany. In fact,

he had been a pretty low-ranking officer. He was very valuable to Washington, though, because he had years of experience training soldiers. And since most of the American volunteers had come straight from farms or workshops, they didn't know much about what soldiers were supposed to do.

he had been a pretty low-ranking officer. He was very valuable to Washington, though, because he had years of experience training soldiers. And since most of the American volunteers had come straight from farms or workshops, they didn't know much about what soldiers were supposed to do.

Steuben got up at three in the morning each day to begin work. He broke the soldiers into small groups, personally showing each group how to work together in battle. The only problem was, he didn't speak much English. When soldiers misunderstood Steuben's commands, he often exploded into red-faced fits of shouting and cursing. First he cursed in German, then in French. Finally, he called to his translators:

“My dear Walker and my dear Duponceau, come and swear for me in English.

These fellows won't do what I bid them.”

The men laughed. Then they tried the exercise again. And again, and again. Joseph Plumb Martin, who was one of the many soldiers trained by Steuben that spring, noticed that the men seemed to have a new energy and confidence. They were eager to get out of Valley Forge and win some battles in 1778.

Friedrich von Steuben

I

n June 1778, the British army marched out of Philadelphia under the command of General Henry Clinton (General Howe had gotten sick of the war and decided to go home). The British had enjoyed the capital city, but now it was time to get back to the business of attacking Americans.

n June 1778, the British army marched out of Philadelphia under the command of General Henry Clinton (General Howe had gotten sick of the war and decided to go home). The British had enjoyed the capital city, but now it was time to get back to the business of attacking Americans.

On his way out of town, John André stole everything he could carry from Ben Franklin's house, including scientific instruments and a large painting of the famous American.

Washington was ready for a fight himself. And on a scorchinghot day in late June, the Americans attacked Clinton's army in Monmouth, New Jersey.

In spite of the high hopes, this was another disappointing day for George Washington. He had made the mistake of putting a general named Charles Lee in charge of leading the attack. Lee was famous for his strange habits, including wearing filthy clothes and bringing his dogs to fancy dinner parties.

When the battle began, Lee decided not to follow Washington's plan (Lee considered himself to be much smarter than Washington). Lee attacked for a little while, then ordered the army to retreat. The soldiers stood around, wondering what to do next. That's when a furious Washington rode up, and this conversation was heard:

Washington:

General Lee! What are you about?

General Lee! What are you about?

Lee:

Sir?

Sir?

Washington:

I desire to know, sir, what is the reason for this disorder and confusion?

I desire to know, sir, what is the reason for this disorder and confusion?

Lee:

The American troops would not stand the British bayonets.

The American troops would not stand the British bayonets.

Washington:

You damned poltroon

[

coward

]â

you never tried them!

You damned poltroon

[

coward

]â

you never tried them!

It was the only time American officers ever heard George Washington swear. So you know he was pretty mad.

While Washington tried to organize his soldiers, the temperature soared to one hundred degrees. As they did in many battles, brave women earned the nickname “Molly Pitcher” by carrying pitchers of water to men on the battlefield. Soldiers needed the water to cool down their blazing cannons (and to drink, of course).

One of the most famous “Molly Pitchers” was Mary Ludwig Hays. She dodged bullets at Monmouth to deliver water to her husband's cannon crew. When Mary's husband fainted from the heat, she stepped up to his cannon and started blasting it at the British. Joseph Plumb Martin saw the whole thing: “A cannon shot from the enemy passed directly between her legs without doing any other damage than carrying away all the lower part of her petticoat.”

Like so many American Revolution battles, this one had no clear winner. And by the end of 1778, the Americans were no closer to winning the Revolution.

General Lee, by the way, was kicked out of the Continental army for disobeying orders. “Oh, that I were a dog, that I might not call man my brother!” he cried.

Other books

Countdown by Fern Michaels

This Old Rock by Nordley, G. David

The Lemur by Benjamin Black

The Kidnapped Bride (Redcakes Book 4) by Heather Hiestand

Cinderella by Ed McBain

The October Light of August by Robert John Jenson

Todd, Charles by A Matter of Justice

THE TORTURED by DUMM, R U, R. U. DUMM

Sure of You by Armistead Maupin

Cataclysm by Karice Bolton