King George

Authors: Steve Sheinkin

For Adriano, Louis, and all the other students

who showed me the light.

who showed me the light.

-S.S.

Table of Contents

Title Page

How to Start a Revolution

How to Start a Revolution

Step 1: Kick Out the French

Step 2: Tax the Colonists

Step 3: Hang the Taxman

Step 4: Try, Try Again

Step 5: Refuse to Pay

Step 6: Send in the Warships

Step 7: Fire into a Crowd

Step 8: Keep the Tea Tax

Step 9: Throw a Tea Party

Step 10: Pay the Fiddler

Step 11: Stand Firm

Step 12: Make Speeches

Step 13: Let Blows Decide

Step 2: Tax the Colonists

Step 3: Hang the Taxman

Step 4: Try, Try Again

Step 5: Refuse to Pay

Step 6: Send in the Warships

Step 7: Fire into a Crowd

Step 8: Keep the Tea Tax

Step 9: Throw a Tea Party

Step 10: Pay the Fiddler

Step 11: Stand Firm

Step 12: Make Speeches

Step 13: Let Blows Decide

The Great Race to Yorktown

Refreshments for the Enemy

Another Wasted Year?

Part 1: The King Tries the South

Part 2: Bad Peaches, Bad General

Part 3: British Behaving Badly

Part 4: The Swamp Fox

Part 5: Fight, Lose, Fight Again

Part 6: Cornwallis Gets Tired

Part 7: Spying on Cornwallis

Part 8: Pick a Port, Any Port

Part 9: The French Sail North

Now Back to Washington

The Trap Slams Shut

Huzzah for the Americans!

A Shell! A Shell!

The White Handkerchief

The World Turned Upside Down

It Is All Over!

One Last Story

This Is Goodbye

Another Wasted Year?

Part 1: The King Tries the South

Part 2: Bad Peaches, Bad General

Part 3: British Behaving Badly

Part 4: The Swamp Fox

Part 5: Fight, Lose, Fight Again

Part 6: Cornwallis Gets Tired

Part 7: Spying on Cornwallis

Part 8: Pick a Port, Any Port

Part 9: The French Sail North

Now Back to Washington

The Trap Slams Shut

Huzzah for the Americans!

A Shell! A Shell!

The White Handkerchief

The World Turned Upside Down

It Is All Over!

One Last Story

This Is Goodbye

Entire books have been written about the causes of the American Revolution. You'll be glad to know this isn't one of them. But you really should understand how the whole thing got started. After all, if you ever find yourself ruled by someone like King George, you'll want to know what to do. So here's a quick step-bystep guide to starting a revolution.

L

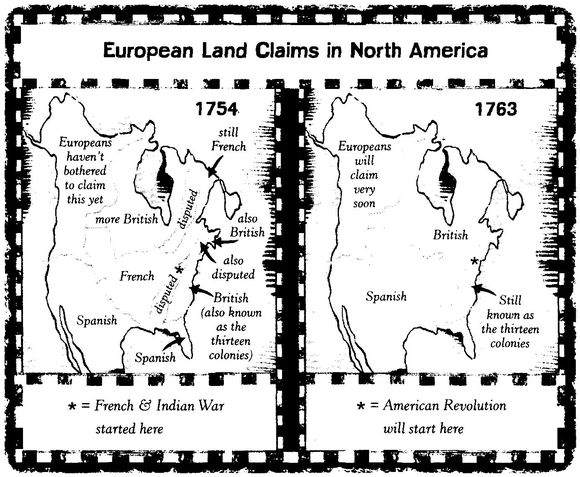

et's pick up the action in 1750. Britain, France, and Spain had carved up North America into massive empires, as you can see on the map below. You'd think they'd be satisfied, right? But Britain and France both wanted to see their names on even more of the map. Let's face it, they both wanted the

whole

map. (It didn't bother them that most of the land actually belonged to Native Americans.)

et's pick up the action in 1750. Britain, France, and Spain had carved up North America into massive empires, as you can see on the map below. You'd think they'd be satisfied, right? But Britain and France both wanted to see their names on even more of the map. Let's face it, they both wanted the

whole

map. (It didn't bother them that most of the land actually belonged to Native Americans.)

To Britain and France, this seemed like a good reason to fight a war. You can call it the French and Indian War or the Seven Years Warâeither way, the British won. Britain took over most of France's land in North America. For Britain, this was the good news.

H

ere's the bad news: war is really expensive. The British were left with a mountain of debt. And now they had to keep 10,000 soldiers in North America to protect all their new land. That's not cheap. The British prime minister George Grenville started thinking of ways to raise some quick cash. You can guess the idea he came up with, can't you?

ere's the bad news: war is really expensive. The British were left with a mountain of debt. And now they had to keep 10,000 soldiers in North America to protect all their new land. That's not cheap. The British prime minister George Grenville started thinking of ways to raise some quick cash. You can guess the idea he came up with, can't you?

That's right: he decided to tax the British colonists. Grenville really felt that the thirteen colonies owed Britain the money. As he put it:

“The nation has run itself into an immense debt to give them protection; and now they are called upon to contribute a small share toward the public expense.”

Grenville's plan was called the Stamp Act. When colonists signed any legal document, or bought paper goods like newspapers, books, or even playing cards, they would have to buy stamps too (the stamps showed that you had paid the tax). A few members of Parliament warned that the Stamp Act might spark protests in the colonies. But young King George III (he was twenty-two) liked the idea. He didn't expect any problems.

George Grenville

K

ing George never did understand Americans. No one likes a tax increase, no matter what the reasons. Besides, the thirteen colonies had been pretty much governing themselves for years. And selfgovernment obviously includes coming up with your own taxes. So colonists started shouting a slogan:

ing George never did understand Americans. No one likes a tax increase, no matter what the reasons. Besides, the thirteen colonies had been pretty much governing themselves for years. And selfgovernment obviously includes coming up with your own taxes. So colonists started shouting a slogan:

“No taxation without representation.”

Tax Protester

Meaning basically, “We're not paying!”

Shouting is easy, but how do you actually avoid paying the tax? Samuel Adams of Boston had that figured out. Adams was in his early forties, and he hadn't really found anything he was good at yet. His father once gave him one thousand pounds (a lot of money) to start a business. Samuel loaned half of it to a friend, who never paid him back. It's safe to say Samuel had no talent for business. All he wanted to do was write about politics and argue in town meetings. How far can that get you in life?

Pretty far, actually. Because when the time came to protest the Stamp Act, Adams was ready to take the lead. He figured it like this:

The Stamp Act is supposed to go into effect in November 1765, right? Well, what if there's no one around to distribute the stamps? Then we won't have to buy them. Simple.

The Stamp Act is supposed to go into effect in November 1765, right? Well, what if there's no one around to distribute the stamps? Then we won't have to buy them. Simple.

The job of distributing the stamps in Boston belonged to a man named Andrew Oliver. When Oliver woke up one morning in August, he was informed that a full-size Andrew Oliver doll was hanging from an elm tree in town. Pinned to the doll was a nice poem:

“What greater joy did New England see,

Than a stamp man hanging on a tree?”

Than a stamp man hanging on a tree?”

It got worse. That night a crowd of Bostonians, yelling about taxes, cut down the doll and carried it to Oliver's house. They chopped off its head and set it on fire. Then they started breaking Oliver's windows.

As you can imagine, Andrew Oliver found this whole experience fairly frightening. He wasn't so eager to start giving out the stamps in Boston.

That was exactly how Adams had planned it. Similar scenes took place all over the thirteen colonies. Calling themselves Sons of Liberty, protesters gave plenty of stamp agents the Andrew Oliver treatment. The agents quit as fast as they could. (Can you blame them?) So when the tax went into effect, there was no one around to collect it.

B

ack in London, the British government was forced to face a painful factâthere was no money in this Stamp Act deal. Parliament voted to repeal (get rid of) the tax. King George reluctantly approved this decision.

ack in London, the British government was forced to face a painful factâthere was no money in this Stamp Act deal. Parliament voted to repeal (get rid of) the tax. King George reluctantly approved this decision.

Colonists celebrated the news with feasts and dances. Boston's richest merchant, a guy named John Hancock, gave out free wine and put on a fireworks show outside his house. The happy people of New York City built a statue of King George and put it in a city park. (Remember that statue; it will be back in the story later.)

What the colonists didn't realize was that British leaders were already talking about new taxes. After all, the British government still needed money. And most leaders still insisted that Britain had every right to tax the Americans. King George was especially firm on this point. He was a very stubborn fellow.

So Parliament passed the Townshend Acts in 1767. When colonial merchants imported stuff like paint, paper, glass, and tea, they would now have to pay a tax based on the value of each item. Or would they?

R

ather than pay the new taxes, colonists started boycotting (refusing to buy) British imports. Women were the driving force behind these boycotts. Hannah Griffitts of Pennsylvania expressed the determination of many colonial women in a poem:

ather than pay the new taxes, colonists started boycotting (refusing to buy) British imports. Women were the driving force behind these boycotts. Hannah Griffitts of Pennsylvania expressed the determination of many colonial women in a poem:

“Stand firmly resolved and bid Grenville to see

That rather than Freedom, we'll part with our tea.

And well as we love the dear draught

1

when a'dry

As American Patriots our taste we deny.”

That rather than Freedom, we'll part with our tea.

And well as we love the dear draught

1

when a'dry

As American Patriots our taste we deny.”

John Hancock found another way to get around paying taxes. Hancock simply snuck his goods past the tax collectors. He knew that smuggling was illegal, but he didn't feel too guilty about it. To Hancock, smuggling seemed like a fair response to an unfair law.

Of course the British wanted to stop smugglers like Hancock. But you have to remember, colonists really hated these taxes. So any British official who tried too hard to collect taxes was taking a serious risk. Think of poor John Malcolm, for example. This British official was stripped to the waist, smeared with hot tar, and covered with feathers from a pillow. Then he was pulled through Boston in a cart, just to make the humiliation complete. What was the worst thing about getting tarred and feathered? Malcolm said the most painful part was trying to rip the tar off his burned body. He mailed a box of his tar and feathers, with bits of his skin still attached, to the British government in London. They sympathized. They sent him money.

Hannah Griffitts

Then, in the spring of 1768, Hancock's ship

Liberty

(full of smuggled wine from France) was seized by tax agents in Boston. Furious members of the Sons of Liberty gathered at the docks, where Sam Adams was heard shouting:

Liberty

(full of smuggled wine from France) was seized by tax agents in Boston. Furious members of the Sons of Liberty gathered at the docks, where Sam Adams was heard shouting:

“If you are men, behave

like men! Let us take up arms immediately and be free!”

like men! Let us take up arms immediately and be free!”

Samuel Adams

The Sons spent the night throwing stones at the tax collectors' houses. They even dragged a tax agent's boat out of the water and lit it on fire in front of John Hancock's house. The terrified taxmen escaped to an island in Boston Harbor.

Other books

The Bad Boys' Reluctant Woman by Sam Crescent

Healing the Clan: Alaskan Tigers: Book Ten by Marissa Dobson

My Misspent Youth by Meghan Daum

The Language of Souls by Goldfinch, Lena

Sudden Death by Álvaro Enrigue

Contact! by Jan Morris

Deadly Desire by Audrey Alexander

The Moor's Last Sigh by Salman Rushdie

Roads of the Righteous and the Rotten (Order of Fire Book 1) by Kameron A. Williams

Vacation Hell: Princess of Hell #4 by Eve Langlais