Kierkegaard (13 page)

Authors: Stephen Backhouse

Overall, the intense, honest attention was welcomed by others. In personal relations, Søren would often employ a psychological directness that eschewed the normal platitudes of everyday chatter. His letters to mourning or infirm acquaintances, for example, show a man who faces difficulties directly and thereby validates the person experiencing the problem. Hans Brøchner recalled with fondness the way Søren once helped a grieving widow of a friend. “

He comforted

not by covering up sorrow but first by making one genuinely aware of it, by bringing it to complete clarity.” A case in point is Søren's cousin, Hans Peter, who was granted rare permission to visit Søren at home rather than on the street. Peter (as he was known) was paralysed on one side, and the infirmity seems to have awakened in Søren a kinship of feeling for a fellow awkward figure. The two would spend hours talking together, with Søren unapologetically transmuting Peter's condition into a spiritual treatment of a man with physical weakness in a section of

Upbuilding Discourses in Various Spirits.

Peter was deeply touched by the attention. “

He is so unspeakably loving

and understands me so well, but I am really afraid to make use of his arm when he offers it to me to help me into my carriage.”

Back out on the streets, there was another reason for the city walks. At the same time Copenhagen was illuminating the human condition to Søren, it was also helping the secretive author hide in plain sight. In

The Point of View

, written near the end of his life, Søren claims he used these public appearances as a way to keep up his authorial project of indirect communication. The city walks served as a way of disguising just how much time and effort was going into the authorship, which was supposed to be by many different people. Often, while writing and editing these works, Søren had no time to walk as he would like. So instead he arranged to be at the theatre for ten minutes at a time, presumably during the intervals. This way the “gossipmongers” would still see him and the word would be put about that as Søren was always out and about, he couldn't possibly also be the author of all these serious works.

The secretive and pseudonymous element of his project was not incidental to the authorship. It was essential to it. This way deeply autobiographical elements could be obfuscated behind a cloud of misdirection and absurd characters, pious reflections could appear alongside scandalous anecdotes, and letters of protest to newspapers could shift attention from Kierkegaard onto his pseudonyms and

vice versa.

Pseudonymity provided the means by which Søren could explore and present different points of view without having to claim each account as his own. It enabled him to draw from his own personal life without making him and his loved ones the object of direct examination. It was also just a lot of fun.

He may have perfected the art, but by no means were pseudonyms a Kierkegaardian invention. The literary world of Golden Age Denmark was positively lousy with them. In a culture in which newspapers were the medium by which intellectual conversations were carried out in public, pseudonymity (or anonymity) was a literary convention followed by almost everyone. Copenhagen was a small city; pseudonyms allowed people to express their views forthrightly without also having to meet their opponents the next day on the street. The practice could be spiteful, but more often than not it was playful, with authors deliberately constructing pen names that hinted cheekily at the man behind the curtain. (Bishop Jakob Peter Mynster, for example, often wrote under the initials “Kts,” the middle letters of each of his names.) Some pseudonyms remained mysterious, while others appeared with enough regularity in journals and newspapers that the true identity of their owners became an open secret. Pseudonymity was a game, and like any game it had rules, the first being that you did not talk about pseudonymity. To publicly identify an author with his pen name was considered bad taste. People who refused to respect the deliberate disguise of others had to be prepared to face the consequences.

It was for this reason that Søren chose an editor of the

Fatherland

newspaper as his prime helper when proofreading the disparate elements of

Either/Or.

During the winter of 1842â43 Søren was a frequent visitor

to the offices of J. F. Giøwad. He liked Giøwad because of his reputation for protecting the identity of his anonymous contributors and because of the editor's discretion in other matters too. Often when at Giøwad's, Søren had “

strong attack

s of his suffering so that he would fall to the floor, but he fought the pain with clenched fists and tensed muscles, then took up the broken thread of the conversation again, and often said: âDon't tell anyone; what use is it for people to know what I must bear?' ” It is clear that Giøwad liked Søren, and the two would talk for hours on end. Their mutual respect did not spill out to the rest of the office. Another assistant editor, Carl Plough, would later bemoan the “

impractical and very self-absorbed

man sitting in the office, ceaselessly lecturing and talking without the least awareness of the inconvenience he is causing.” Søren had enlisted Giøwad for his cause, but to ensure the success of his impending authorial onslaught he used the

Fatherland

to publish a “Public Confession” in the June 12, 1842, edition. The article (written by Søren) urges the good people of Copenhagen never to regard Søren as the author of anything that does not bear his name. (Incidentally Søren was luckier with Giøwad than with his other choices of assistants. Around this time he also enlisted the help of a poor theology student, P. V. Christensen, as a scribe and proofreader. Søren soon regretted letting

“my little secretary”

in on his secrets, however, and later that year had to fire him on suspicion of plagiarism. “

I wager

that he is the one who in various ways is scribbling pamphlets and things in the newspapers, for I often hear the echo of my own ideas.”)

The ground thus prepared,

Either/Or

was published February 20, 1843. If the literary wags of Copenhagen liked their pseudonyms, they were possibly about to get too much of a good thing. This is the book that began the dialectical movement through the stages of Christendom, but it is also the one that put the complex “Russian doll” pattern of the authorship into play. Victor Eremita is responsible for

Either/Or

, but he claims he is not the author. With Kierkegaard, even the pseudonyms have pseudonyms, and Victor (whose Latin name means “victorious hermit”)

is supposedly merely editing a collection of papers that he found hidden in an old desk, one set written by “A,” a young, hedonistic man, and another by “B,” who may or not be “A” as an old man but who in any case is actually revealed to be a moral character named Judge William, who supports marriage by objecting strenuously to “A” and to another essay in the book called the “Diary of a Seducer” by someone named

Johannes. Got it? Other books would contain the same bewildering teases. Constantine Constantius is the “constantly constant” author of

Repetition,

an elliptical novel that also contains the thoughts of an unnamed “Young Man” who is working through the implications of a failed romance. On October 16, 1843, the same day

Repetition

hit the shelves, another mysterious tome called

Fear and Trembling

appeared. Its author, Johannes deSilentio (“John the silent one”), lives up to his name by trying to understand the story of Father Abraham and his son Isaac, by retelling it multiple times in various ways. His attempts to understand Abraham's faith fail, and in the end Johannes confesses, in a wordy and eloquent manner, that he must shut up. June 13, 1844, saw

Philosophical Fragments

by Johannes Climacus, who shares a name with a medieval monk, and whose name literally means “John the climber.” Climacus's extended reflection on history, reason, and the Absolute Paradox of the incarnation is followed five days later by Vigilius Haufniensis (the “vigilant watchman”), whose book

Concept of Anxiety

ponders the role that

angst

over inherited sin plays in making a human an authentic person. It is all getting complicated, but never fear! Readers discomfited by paradox and dread could quickly turn to a slighter book, also published on June 17, 1844, called

Prefaces,

and whose subtitle purports to offer “

Light reading for the different classes at their time and leisure.

” Its author, Nicholas “notewell” Notabene has been forbidden by his wife to write any books, so as a loophole he has produced a series of prefaces to books that have never been written, taking the wind out of public luminaries like Heiberg and Martensen along the way. The next year, on April 30, 1845, Hilarius Bookbinder does one better. His monstrous book,

Stages on Life's Way

, is a compilation of a veritable army of pseudonyms. Here we meet again Johannes the Seducer, Victor, Constantine, a tailor, and Judge William, who is still busy defending marriage.

Stages

also finds room for Frater Taciturnus (“Brother Silence”), who fishes a diary out of a lake. The journal, entitled “Guilty?/Not Guilty?” is by someone named Quidam. It details his descent into madness after breaking troth with

the cheerful and beautiful Quaedam. Yet it soon becomes apparent that the waterlogged diary is about more than love, for in it we are also introduced to a “bookkeeper” who bears a striking resemblance to a former merchant hosier of the city and who is labouring under a guilty burden he cannot shake off.

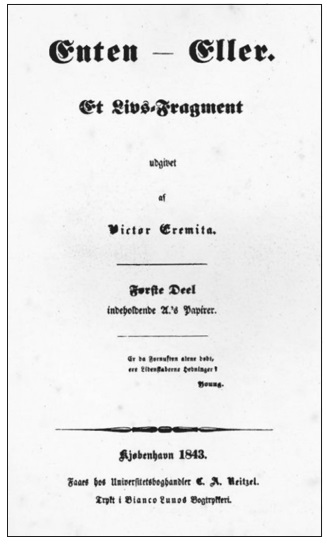

Original 1843 title page for the first edition of

Either/Or

, the book Søren considered the true beginning of his “authorship” proper.

Despite the clear autobiographical elements for those with eyes to see, Søren took pains to distance himself from this portion of his authorship. He would never be able to hide his involvement completely, however, as he was fully aware. All his books, he wrote to Emil, are “

healthy, happy

, merry, gay, blessed children born with ease and yet all of them with the birthmark of my personality.” It is worth stressing that not all pseudonyms were created equal. Søren occasionally prevaricated over to whom he would ascribe an already-written manuscript. For example,

Concept of Anxiety

was going to be published under Kierkegaard's own name until a few days before the manuscript went to the printer. In the end, the book contains a highly personal dedication to Søren's teacher, P. L. Møller, passing without comment over the curious coincidence that Vigilius Haufniensis also considered the deceased philosopher to be a personal friend and inspiration. The case of

Anxiety

highlights the caution one must take over reading

too

much into the pseudonyms, but it also highlights the fundamentally playful nature of the pseudonymous project itself. The pseudonyms are not watertight, neither are they meant to deceive utterly and completely. Instead, pseudonymity is a mechanism by which the reader is forced to pause and consider their own relation to the text rather than to the author. Søren clearly enjoyed playing the pseudonymous game with his public. At various times he arranged for Victor Eremita, “A.F.” and an “Anonymous” letter writer to reply to critics in the newspapers, and to offer their theories as to the true author of the books. Anyone familiar with the practice of “sock-puppetry” on internet message boards (where one user creates many aliases and uses them to converse with each other) will recognise what Søren was doing with the newspaper technology of his day. In May 1845, he wrote a letter

to the

Fatherland

under his own name, objecting to the free-and-easy association that an enthusiastic reviewer had made between Kierkegaard the author of the

Upbuilding Discourses

and the author(s) of such works as

Either/Or

and

Stages on Life's Way

. Even here, however, the objections are tongue-in-cheek. Everyone knew, or strongly suspected, that Kierkegaard was the real author, and he knew that everyone knew. Still, the playful charade needed to be kept up for the sake of the authorship as a whole.

The pseudonyms were only part of the authorship. Søren considered the self-penned

Upbuilding Discourses

to be as essential to his output as the books ascribed to the others. There are twenty-one

Discourses

in all, brought out in batches that roughly correspond to the pseudonymous publications. The first two arrived on May 16, 1843, a couple of months after

Either/Or

. Three more entered the shops the same day (October 16) as

Fear and Trembling

and

Repetition

. December 6 saw four

Discourses

, March 5, 1844, saw two and June 8 three more, five days before

Philosophical Fragments

hit the shelves and less than ten days before

Concept of Anxiety

and

Prefaces

burst onto the scene. Readers had a couple of months to get their bearings before tackling four more

Discourses

on August 31, but they would have to wait until April 29, 1845, before they could be edified by the final

Three Discourses on Imagined Occasions

, which handily arrived a day before

Stages on Life's Way

.