Kierkegaard (12 page)

Authors: Stephen Backhouse

Søren is cut to the heart when he receives this piteous letter. Nevertheless, there is nothing else for it. She has not succumbed to the first sally, so the attack must press on. Søren had at last convinced himself that the break-up was for her own good, as well as his. Thus, he tells himself, “

I have to be cruel

in order to help her.” What follows is a liar's campaign, which Søren refers to as a “time of terrors.” To dump Regine now is to publicly humiliate an innocent girl, so Søren needs to convince everyone else that the breach is for her own good and for Regine to think it is her own idea. She believes (rightly) that he still loves her and so will not release him. So he must convince her of that which is not true. Over the next two months he adopts an attitude of cruel and calculated indifference. He refuses to meet. He acts cool towards her in public. He ceases to reciprocate her love letters and sends cold notes instead. He reverts to his old gadabout ways. He acts, in his own words, like a “

scoundrel

. . . an arch-scoundrel.”

As with many of Søren's schemes, it does not work quite as planned. True, most people in town think he is a villain, and even friends like Sibbern become concerned at Søren's high-handedness. Regine's family are confused. Regine's sister Cornelia is puzzled and does not know what to think. Her brother Jonas is more forthcoming, writing an

angry letter

to Søren claiming that he has never learned what it was to hate until now.

The one person the plan is not working on is Regine. “

She fought

,” Søren would later write, “like a lioness.” It is only the belief that he has divine approval of his cause that allows him to persist with his ironic campaign.

“Give up, let me go; you cannot endure it,” Søren tells her one day.

“I would rather endure everything than let you go,” Regine replies.

“You will never be happy anyway,” she says another day with impeccable logic. “So it cannot make any difference to you if I am permitted to stay with you.”

Finally Søren cracks. “You should break the engagement,” he says directly, “and let me share all your humiliation.”

Regine will have none of it. She tells Søren that if she can bear his actions now she can bear the public humiliation. Let them talk, she says, besides, “very likely no one would let me detect anything in my presence and what they said about me in my absence would make no difference.”

She is impervious. Søren admires her more than ever. For him too the ordeal was “a frightfully painful timeâto have to be so cruel and to love as I did.”

They are at an impasse entirely of Søren's making. It is during this stressful time that Søren is called to defend his doctoral dissertation. The work is published on September 16, giving enough time for people to prepare their questions for the disputation panel on September 29. The thesis may have been written in Danish, but the public defence is carried out in Latin. It lasts for seven-and-a-half hours and includes questions from interested members of the public such as a hostile Heiberg and Søren's brother, Peter. History does not record whether Peter was hostile or not. In any case, Søren acquits himself admirably, and, at the end of the ordeal, he is granted the right to use a new title:

Master

.

Less than two weeks later, matters with Regine come to a head. On October 11, the newly minted Master Kierkegaard goes to the Olsens to finish the process begun months before. Even nowâ

especially now

âat the end of it all, Søren maintains his caddish facade. After breaking the news to Regine, he callously looks at his watch and announces that he is late for the theatre and a meeting with his friend Emil Boesen. “

The act,

” he reports in his journal, “was over.”

But Søren has yet again underestimated his opponents. After the play, Counsellor Olsen approaches Søren in the stalls.

“May I speak with you?” he asks. “She is in despair. It will be the death of her. She is in utter despair.”

“I will try to calm her,” Søren says loftily, “but the matter is settled.”

Terkild, normally so staid, has to collect himself. “I am a proud man,” he says. “This is hard, but I beg you not to break with her.”

Terkild's magnanimity jolts Søren, and at the father's invitation he meekly returns to the scene of the crime. He eats with the family and speaks briefly to Regine. The next day Søren receives yet another note. The girl has not slept, and she begs Søren to come and see her.

“

Will you never marry

?” Regine asks. What she said about not sleeping is true, and it is clear she has been crying all night.

It is hard, but Søren keeps up the act. “Yes,” he replies breezily, “in ten years' time, when I have had my fling, I will need a lusty girl to rejuvenate me.”

From her person, Regine takes out a piece of paper containing some lines that Søren had written to her. The paper has been lovingly folded and unfolded many times. Now Regine tears the paper into little pieces. “So you have been playing a dreadful game with me. Do you not like me at all?”

Søren sets his face. “Well, if you keep on this way I will not like you.”

“If only it will not be too late when you regret it,” she cries. “Forgive me for what I have done to you.”

It is altogether too much to bear. Here, at the end, the mask slips. “I'm the one, after all, who should be asking that,” replies Søren, broken at last.

“Kiss me,” she says. He does.

“Promise to think of me,” she says. He does. And takes his leave of the last full conversation the two will ever have.

Outwardly, Søren has attained his aim. The engagement is ended beyond all repair, and the Olsens, finally, are scandalised. Copenhagen's social circle is convinced of Søren's guilt, and the town is filled with gossip about the various ways he has publicly humiliated the longsuffering

Regine. Privately, Søren is distraught. At a family gathering he breaks down weeping in front of his nephews and nieces. He spends his nights

“crying in my bed.”

Peter Kierkegaard, ever vigilant about the family reputation, seeks to limit the damage by putting it about that Søren is not, after all, quite the hard-hearted scoundrel he seems.

“If you do that,”

Søren warns, “I'll blow your brains out.”

On October 25, Emil and Peter accompany Søren to the docks. He needs to get away and has decided to live in Berlin for a few months. The trip marks the end of Søren's aborted career as a respectable family man and the beginning of a new phase of Søren the writer. It is in Berlin that Søren will break the back of the first book of his “authorship,” and it is in Berlin that Regine the flesh-and-blood girl completes the transmutation into Regine the symbol of faith, marriage, and love unrequited.

No request has been expressed as completely and utterly in vain as was Regine's request that Søren think of her “from time to time.” For the rest of his life not a moment will pass when she does not cross his mind. “

I was reminded of her

every day. Up to this day I have unconditionally kept my resolve to pray for her at least once every day, often twice, besides thinking about her as usual.” Søren had given her a diamond ring, set in gold, for their engagement. Upon its return, he had the ring reset, arranging the four diamonds into the pattern of a cross. It was a constant reminder of his renunciation in service of God, and he wore it until his death. Søren never stopped writing about Regine. She and her analogues would haunt his books for years to come, his pseudonyms constantly leaving clues to the relationship for those with eyes to see. The private journals were less mysterious. After Søren's death, they will find amongst his papers reams of writing about Regine, including this entry from 1848: “

The few scattered days

I have been, humanly speaking, really happy, I always have longed indescribably for her, her whom I have loved so dearly and who also with her pleading moved me so deeply.”

Writing Life

It is the winter of 1842, and Søren is walking the streets of Berlin. In fact he is sauntering down the same road that he has walked many, many times. For on this street is located a fine shop with a fine shop window, and in this fine shop window is a fine walking stick. Søren has tempted himself with this stick before, but today, as a little New Year's present to himself, he decides to take the plunge. Søren straightens his coat collar and assumes a nonchalant air before entering the shop. It would not do for the seller to know just how much the buyer wants his wares! Søren is so intent on striking just the right pose of friendly enthusiasm mixed with studied indifference that he becomes tangled on the doormat, breaking the window on the door. “

After which I decided to pay

for the pane and not purchase the stick.”

Søren left for Berlin on October 25, 1841, shortly after breaking with Regine. He would return to Copenhagen on March 6, 1842. There would be two more short trips to Germany in the ensuing years, but these five months mark the longest time Søren ever spent away from home.

He was hapless abroad. Initially, Søren felt real pleasure in speaking another language. At first he wrote with interest about what it does to one's identity to have to express oneself in a foreign tongue. It wasn't long before the bloom wore off that particular rose, however. Søren's ability to speak, write, and think in Danish, Latin, Hebrew, and Greek did not extend to German, and he did not get along well in that language. He was confused

by the orders barked at him by train conductors and had difficulty ordering the simplest things, like more candlesticks for his room. One such tortured interaction led to Søren being ripped-off by his landlord.

Søren's uneasiness extended to his manner when out and about in Berlin. For one thing, he felt a stranger in this city that seemed so inhospitable to nature's call. He was discomfited by Berlin's lack of public toilets. In one letter he complained that he had to carefully time his walks so he could arrive at “

a particular nook

in order to p.m.w. [pass my water] . . . In this moral city one is practically forced to carry a bottle in one's pocket.” Another occasion saw Søren enter a fancy restaurant with some friends. On seeing a phalanx of important-looking men wearing starched collars and tails, he made his way over and formally introduced himself. After a few minutes of stilted conversation, Søren rejoined his party at the table, only to discover that the grandees of Berlin society he had been speaking to were, in fact, his

waiters

for the night.

To avoid the constant

faux pas

, Søren naturally gravitated towards other Danes abroad, such as at Spargnapani's, a cafe that was a favourite haunt of Danish expats. Yet even here Søren was out of place and awkward. Reporting home to his mother about the Danish cafe culture in Berlin, another tourist, Caspar Smith, wrote, “

Søren Kierkegaard

is the queerest bird we know: a brilliant head, but extremely vain and self-satisfied. He always wants to be different from other people, and he himself always points out his own bizarre behaviour.”

What Caspar was never to know was that Søren was carefully managing his appearances amongst the Danish set. Søren did not leave behind his tendency to micromanage his reputation when he left home. If anything, the tendency became more pronounced, and for the same reasons. In Berlin, as in Copenhagen, the (attempted) reputation management was all for Regine's benefit. In letters to his friend Emil Boesen, Søren admits to frequent ill health but downplays it in public and dares not be seen to consult with a

doctor

, for fear of the expatriate Danes. The danger was that if they wrote home and mentioned the news in passing,

Regine might hear that Søren was not, in fact, living the high life in Berlin. “

Here, a groan

which might, after all, possibly mean something entirely different, might reach the ear of a Dane, he might write home about it, she might possibly hear it.” Søren needed Regine to think he was happy, healthy, and productive, which would supposedly increase her ability to despise him and move on with her life. Søren's frequent letters to Emil are filled with detailed instruction as to how his friend should spy on the girl to track whether his scheme of holy deception was working. He tells Emil where, and at what times, he will be best placed to observe Regine but gives strict orders not to approach or speak with her. In other letters, Søren seems to be feeding information to Emil that he hopes will make its way into general circulation amongst Copenhagen's

chattering class. He wants the Olsen family to hate him, and so, for example, he includes in a letterâon a separate sheet of paperâa curious note about having romantic designs on a Berlin opera singer who “

bears a striking resemblance

to a certain young girl.” Søren knows the gossips are out to get him. Is this a roundabout way of tempting Emil to fuel the flames by offering titbits that are easily disseminated? In any case, the Berlin opera singer is never mentioned again. We also do not know to what extent Emil proved pliable as a secret agent. Certainly, we know he disobeyed at least one of Kierkegaard's instructions, for the letters were not burnt as Søren directed.

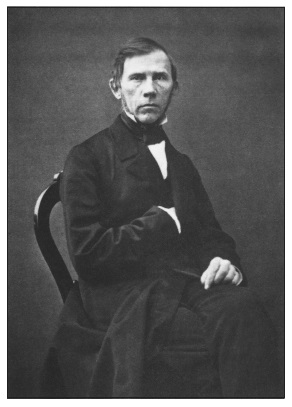

Emil Boesen, Søren's best friend and confidant. Søren occasionally tried to enlist Emil in his campaigns of literary intrigue.

Ostensibly, Søren had gone to Berlin to attend lectures. The university there was a hive of academic activity, attracting philosophers from across Europe. Søren dutifully attended many different series of lectures, but they all disappointed him in one way or another. An especial low point was the series by Friedrich Schelling. Schelling was a famous opponent of Hegelianism, occasionally singled out by name in Hegel's writing. Kierkegaard was keen to witness Schelling in action, as were many, many others. Attendance was packed, and Søren had to jostle for seating amongst a crowd that also included Friedrich Engels and the Russian revolutionary anarchist Mikhail Bakunin.

The series was celebrated, but Søren was disappointed almost from the start. Early on, Schelling's use of “actuality” as opposed to the vague generalities of Hegelian systematising made Kierkegaard perk up. Soon, however, Schelling's promising start gave way to convoluted systems of his own, delivered in an officious, nasal drone that Søren found extremely off-putting. The great man did not acknowledge Hegel's direct criticisms, and he grew querulous when audience members complained about the length of his sessions, which often exceeded two hours. Surprisingly, Søren persisted for forty-one lectures before finally throwing in the towel. “

I am too old

to attend lectures,” he wrote to his brother Peter, “just as Schelling is too old to give them.”

Even so, Søren did not consider his trip to be wasted, for what was

really occupying him during this time was his authorship. He wrote to Emil that he was writing like crazy, but he refused to divulge any more detail and asked his friend not to discuss the project with anyone. “

Anonymity

is of the greatest importance to me.” Søren had gone to Berlin to be free from Regine and to focus on learning and writing away from prying eyes. The months away were invaluable for this purpose. It was necessary to separate himself from his old life in order to break the back on this, the first salvo of the authorship. Yet Søren missed home, and he came to realise that its routines and familiarities also provided a release for him. “

I am coming to Copenhagen

to complete

Either/Or

. It is my favourite idea, and in it I exist.”

From October 1841 through to February 1846, Søren would write and publish thousands of pages of text. In less than five years, the Danish reading public were presented with

Either/Or

(two volumes)

, Repetition

,

Fear and Trembling

,

Philosophical Fragments

,

Prefaces

,

Concept of Anxiety

,

Stages on Life's Way

, and

Concluding Unscientific Postscript.

Many of these volumes were published on the same, or subsequent, days. Running alongside this welter of pseudonymous works, Søren also produced, under his own name, twenty-one “Upbuilding Discourses,” which, by and large, he arranged to come out at the same time as the pseudonymous books. Even the shortest of these works are substantial in their own right and have been subject to sustained scrutiny and academic study. The longest are compendiousâ

Either/Or

runs to 838 pages,

Stages on Life's Way

383, and

Concluding Unscientific Postscript

480. Søren carefully edited every one of his pieces, in some cases rewriting them two or even three times. Some books were partially written before being abandoned. Besides this series of publications, which Søren referred to as his “authorship,” he continued to fill journals and compose newspaper articles, personal letters, and occasional pieces. He would later sum up this time with pithy accuracy: “

To produce was my life

.” In light of this stupendous output, the question that comes to mind is not “Wherever did he find the time to write?” It is instead “Wherever did he find the time to do anything else?”

Søren returned home on March 6, 1842. Apart from two brief trips to Berlin in 1845 and 1846 (each visit lasting less than two weeks) Søren would remain in Copenhagen for the rest of his life. The city itself became crucial to his

writing

process. Lengthy walks around Copenhagen were part of the authorial process, because it was on the city streets that Søren “

put everything into

its final form.” Søren “wrote” while walking. The hiking stage was only the first part of his process. The second stage occurred when he got home, where he would be observed by his servant, Anders Westergaard, standing at his desk, hat still on head and umbrella tucked under arm, furiously scribbling down with his hands the words he had already written by foot.

Yet Copenhagen was no mere inert backdrop. The living, breathing people of the city were key.

I regard the whole city

of Copenhagen as a great social function. But on one day I view myself as the host who walks around conversing with all the many cherished guests I have invited; then the next day I assume that a great man has given the party and I am a guest. . . . If an elegant carriage goes by with four horses engaged for the day, I assume that I am the host, give a friendly greeting, and pretend it is I who has lent them this lovely carriage.

Søren called these excursions his “people bath,” and he became known for plunging into conversation with everyone and anyone, whatever their age and stage. In 1844 Søren remarked that “

although I can be totally engrossed

in my own production, and although together with all this I am doing seventeen other things and talk every day with about fifty people of all ages, I swear, nevertheless, that I am able to relate what each person with whom I have spoken said the last time, next-to-the-last time . . . his remarks, his emotions are immediately vivid to me as soon as I see him, even though it is a long time since I saw him.” Such a claim might seem an exaggeration except for the multiple eyewitness accounts that appear to

affirm the assertion. “

He preferred

to involve himself with people whose interests in life were completely different from his own or which were diametrically opposed to his own.” The sight of Master Kierkegaard gently but firmly taking someone by the arm while walking with them down the street, talking all the while and swinging his walking stick for emphasis, is one well attested by many contemporary Copenhageners.

Some people loved it and found Søren sincere, humorous, and good natured. Others disliked the feeling they were being pumped for information, suspecting they were fodder for a character study in a future book. Both reactions were valid. “His smile and his look were indescribably expressive,” remembered his old friend and tutor Hans Brøchner. “There could be something infinitely gentle and loving in his eye, but also something stimulating and exasperating. With just a glance at a passer-by he could irresistibly âestablish a rapport' with him as he expressed it. The person who received the look became either attracted or repelled.” Brøchner recalled how Søren would “carry out psychological studies” with everyone he met. The practice sounds more sinister than it really was, however. For Søren, a “psychological study” was synonymous with meaningful conversation focussed on the individual before him. Søren, Brøchner tells us, would “

strike up conversations

with so many people. In a few remarks he took up the thread from an earlier conversation and carried it a step further, to a point where it could be continued again at another opportunity.” Undoubtedly some people felt ill-used by the Kierkegaard treatment, such as his secretary Israel Levin. Levin was employed in 1844 as a proofreader and scribe (he would stay on until 1850). Levin was a notoriously cantankerous individual and seems to have been retained by Søren partly for his ornery (and therefore psychologically interesting) nature. A daily fixture in the home, Levin was often drafted into helping prepare the morning

coffee

. He hated this duty, as invariably Søren would ask him to choose a coffee cup from the jumble in the cupboard and then demand that Levin give a personal accounting for why he chose that particular cup on that particular day.