Just in Case (5 page)

Diatomaceous earth (DE) that is suitable for human consumption — not the swimming pool variety — is another good alternative. DE is a white powder composed of the spiny skeletons of tiny marine creatures. After the soft body parts decomposed, the remaining skeletons accumulated on the ocean floor over many thousands of years. Those skeletons are now mined and used for pest control. When a bug ingests the powder along with a nibble of grain, the spiny skeleton tears up its digestive tract and it dies before it can reproduce. DE is not harmful for humans to ingest and it has no taste.

Put about ½ to 1 cup of diatomaceous earth into a five-gallon container of any grain or seed and roll it around until every grain is covered. The food can then be consumed without worry, as this method is nontoxic. The fine powder can irritate lungs and eyes, though, so wear a face mask and eye protection when you work with it.

DRY ICE PRECAUTIONS

Dry ice is very cold — as cold as -100°F — and it will freeze unprotected skin on contact, so it must be handled carefully. Pick it up only with heavy, insulated gloves or tongs. I would not use it around children, as this stuff is just too tempting for curious little ones. Dry ice also causes tremendous pressure when it turns from its solid state to its gaseous state, so it must not be used in glass containers, as it can cause a serious explosion. In spite of these drawbacks, it is an inexpensive and reliable way to fumigate food.

Dry ice is another good option for fumigating food. Dry ice is frozen carbon dioxide. When placed in a container and allowed to evaporate, it replaces the oxygen in the container with carbon dioxide, eliminating all existing bugs and pests. Though eggs or larvae may still be present, they will be dormant. If they manage to survive, they will not be a problem until you open the container. At that point you can freeze the grain or seed to kill the larvae or use the contents before any bug has time to hatch and breed. To use dry ice, wrap a chunk of it in brown paper (an opened paper bag works well) and place on top of a nearly full container. Cover the container loosely so air can escape. When the ice has evaporated (generally this takes twenty to thirty minutes), seal the container and store. Dry ice can be purchased at many grocery stores and from beverage companies.

Once your food is free of pests, the trick is to keep it that way. Bugs can get into any small opening, so I always tuck a couple of bay leaves into my stored grains, beans, and seeds. Bugs don’t seem to like the smell of bay. I also take extra care in sealing the lids of my storage containers. With plastic containers I often wrap the lids in duct tape. With glass containers, I often dip the jar tops into a bowl of melted paraffin. (If a jar is too large to dip, I may paint its lid with two thin coats of paraffin.)

CHOOSING FOOD-STORAGE CONTAINERS

Foodgrade plastic is an excellent material for storage, and foodgrade plastic buckets and gallon jars can often be had for the asking from schools and restaurants. There may be a lingering odor in the plastic buckets, especially if they previously held something like pickles. I wash them in hot soapy water and rinse them in a sanitizing solution of one part bleach to ten parts water, letting the solution sit in the buckets for twenty minutes. Then I drain and rinse them with clear hot water, dry them well, and line them with a foodgrade plastic or metallized bag. This usually solves the odor transfer problem. (Metallized bags can be purchased from preparedness and wilderness-survival companies. Large foodgrade plastic bags are usually available through food-service companies. If you can’t find a source for these large bags, you can pack the food in one-gallon bags that can be purchased in any market and store five in each bucket. Just remove each bag as you need it.) To ensure a good seal I either tape the edge with duct tape or paint the lid seam with two thin coats of melted paraffin.

PARAFFIN PRECAUTIONS

Paraffin is highly flammable. It must be melted over hot water, whether in a double boiler or by setting a can in a pan of hot water. It should not be melted over direct heat, as it can burst into flame. This is another project to start without children underfoot.

Glass gallon jars are wonderful to look at, but they leave you with the problems of breakage and light permeability. If you’re going to use them, handle them carefully and store the jars in paper bags to keep out unwanted light.

Five-gallon buckets are just right for storage, and they stack well. The one downside is that these buckets are very big and, if filled with something heavy such as wheat or flour, may become awkward to lift. The best thing about the buckets is that the lids come with gaskets that really seal the contents from moisture and insects. If you do get a few of these buckets, I would suggest purchasing a bucket opener, which will save you many scraped knuckles and broken nails. There are expensive bucket openers on the market, but my three-dollar model works well for me. I often store items that I don’t want to repack, such as pudding and cake mixes, in these buckets.

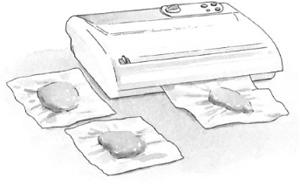

I don’t often recommend buying gadgets. Most take up more space than they are worth and often are not used at all after the first week or two, but I have one appliance that I use all the time, especially for food storage. I inherited a Deni Freshlock vacuum sealer from my mother-in-law, and I love it. Vacuum sealers work like a charm for freezing fruits and vegetables from the garden and also make food storage a lot easier. You can make a bag any size you want, fill it with your food, vacuum out the air, and seal, all in the space of a couple of minutes. Filled bags can be frozen or stored in a cabinet or plastic bucket. The vacuum seal keeps food fresher for longer, and I can pack in only as much as I need at one time. I use my vacuum sealer to store recipe mixes. Before I tried it, I assumed that the vacuum would suck up the mix, but it turned out the suction wasn’t that strong. It is so handy to be able to pull out the one bag I need with everything in it. The bags come on a roll and are expensive. But I bought rolls of premade four-cup bags from a restaurant supply catalog, and that has saved me a lot of money. I also reuse the bags most of the time; I just turn them inside out, wash them, dry them, and then turn them right side out and use them to make smaller bags the next time.

BUCKET OPENER

VACUUM SEALER

Another gadget I have come to love is my Pump-n-Seal, a device for extracting air from jars and sturdy plastic bags. I pack whatever I want to store in a one-gallon jar and cap it. Then I punch a thumbtack-size hole in the lid. I place one of the small tabs that comes with the pump, similar to a small sticker, over the hole, fit the pump over the tab, and pump out the air. The tab seals the hole when I’m done. The result is a vacuum-packed jar that will keep dry foods fresh for many months.

No matter which option you choose for food storage, remember to label the container with its contents, its date of purchase, and a “use by” date. I use a laundry pen and a strip of masking or freezer tape to make labels. Since I always repack items that come in flimsy cardboard or plastic containers into something sturdier, I make sure to include any preparation instructions on an index card taped to the lid of the new container. I forgot to do the labeling once and I now have a jar of either wheat gluten or soy flour or pancake mix in a jar in the pantry. I don’t use it because I’m not sure what it is, and I’m too cheap to throw it away.

What not to use for storage is as important to know as what works. Never use any container that has held toxic material. Do not use plastic garbage bags, as these are often treated with fragrances or pesticides. Make sure to thoroughly clean all of the containers you use, even new ones, in hot soapy water and a sanitizing bleach solution to kill any mold. Rinse containers in clean hot water and dry thoroughly, because any residual moisture will result in mold. In fact, I use my hairdryer to dry hard-to-reach crevices on lids. Fresh, clean food in pristine containers will last much longer and be far more appealing than questionable food in an unsanitary box.

CHAPTER 2 ACQUIRE AND ROTATE

As the clutter and nonessentials move out of your home, you can begin to acquire those things that will see you through a crisis. But how much food do you need? Enough for a month? Or a year? And in what form? Canned or dehydrated? Should you store flour or wheat berries? What about essentials like toilet paper and toothpaste? And how do you keep your supplies fresh? These are questions that must be answered before you begin to fill up all of that newly acquired space if you wish to avoid the all-too-common pitfall of lots of food but nothing to eat.

We will first look at how you can build a food supply tailored to the needs of your particular family.

BUILDING YOUR FOOD SUPPLY

A

CQUIRING A STOCK

of food is the meat (pardon the pun) of a family preparedness plan. Since few of us have the resources to rush to our closest supermarket with a pickup truck and return home with a threemonth supply of food and goods, planning is key. After assessing your family’s needs, as described in

chapter 1

, you can make that plan based on your unique situation and priorities.

Most of us, in spite of owning numerous cookbooks and having access to a seemingly endless array of food options, tend to rotate through the same basic menus. Even if you are more adventurous than most, in a time of crisis you are likely to crave the comfortable and the familiar. This is the very essence of homesickness, the desire for the smells and tastes and textures that make us feel safe. Crisis is not the time to experiment with the unfamiliar, especially in our food. Storing what you eat and eating what you store won’t just protect your food from spoiling. It will ensure that the food you serve your family nourishes them in body, mind, and spirit. A good meal can raise your spirits and energy level like nothing else can.

I have read any number of books on food storage, and while there is a lot of worthwhile information in many of them, a good deal of it isn’t practical for a majority of families. One source suggests first putting by a year’s supply of powdered milk, peanuts, wheat, and tomato juice, since these foods will sustain life almost indefinitely. While that may well be true, I suspect that after a couple of months of tomato juice and peanuts for dinner every night, your body might be okay but your spirits will certainly be flagging.

Many sources tout the superiority of wheat as the foundation of a food storage program. It can be ground, sprouted, boiled, and turned into a rather gummy gluten mass that can be boiled in bouillon and pass for Salisbury steak. I do store some wheat (I grind it into flour), so I decided to give this a try. I followed the directions to the letter and served the results to my kids. They were quick with the verdict: “Nice try, Mom, but this tastes a lot more like a gummy mass boiled in bouillon than any kind of steak, and can we please make tuna sandwiches?”

Other preparedness guides suggest focusing on storage foods that have an incredibly long shelf life, such as dried beans and seaweeds. They offer “homestyle” recipes using these foods, imitating the familiar. To that end, I have tried recipes for, among others, pinto bean fudge and soybean and kelp casserole. Not surprisingly, none of these are high on my family’s list of favorite foods.

Rather than trying to work with the unfamiliar, it makes more sense to customize your storage plan with foods your family already uses and enjoys. Your pantry becomes your grocery store, stocked with everything you need, ready and accessible when things go well or when crisis erupts. If you’ve kept a log of the meals and snacks your family eats over a two-week period, as suggested in

chapter 1

, you’re well on your way to having such a storage plan.

I want to add a word of caution: Don’t believe everything you read. When I began to look into storage food, I read a good deal that was inconsistent. Some foods are said to have an indefinite shelf life, which makes it sound like they’ll last forever. They won’t. All food deteriorates. I have heard some MREs (meals ready to eat) referred to as yummy by one person, while the same food was called vile by another — I guess taste is a personal matter. I have read many conflicting reports on the nutritional quality of dried food versus frozen versus dehydrated versus canned, making it nearly impossible for the average shopper to make an informed decision. Many food storage guides call for complicated mathematical equations to determine needs based on family configuration, and nearly all have food lists that suit the needs of the list maker, not those of me and my family. I looked at all of my options, and here is what I decided would work for us.