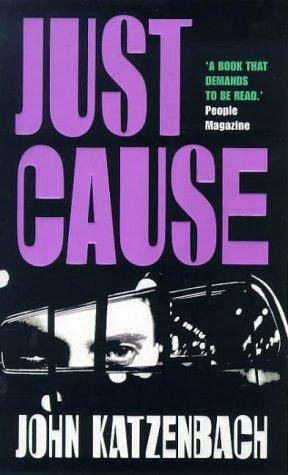

Just Cause

Annotation

Reporter Matt Cowart's explosive investigative journalism succeeds in freeing a convicted rapist and murderer. But has his dedication to freeing "an innocent man" actually turned a ruthless killer loose again?

- John Katzenbach

- ONE. Prisoners

- TWO. The Churchgoer

- 12. The Police Lieutenant's Sleeplessness

- 13. A Hole In The Story

- 14. Confession

- 15. Standing Out

- 16. The Young Detective

- 17. Newark

- 18. The Convenient Man

- 19. Plumbing

- 20. Traps

- 21. Conjunction

- 22. Taking Notes

- 23. Detective Shaeffer's Negligence

- 24. Pandora's Box

- 25. Lost Time

- 26. The Briar Patch

- 27. Two Empty Chambers

- 12. The Police Lieutenant's Sleeplessness

- ONE. Prisoners

Just Cause

ONE. Prisoners

When you win the prize they tell you a joke: Now you know the first line of your own obituary.

On the morning that he received the letter, Matthew Cowart awakened alone to a false winter.

A steady north wind had picked up after midnight and seemed to push the nighttime black away, smearing the morning sky with a dirty gray that made a lie of the city's image. As he walked from his apartment to the street outside, he could hear the breeze rattle and push at a palm tree, making the fronds clash together like so many swords.

He hunched his shoulders together tightly and wished that he'd worn a sweater beneath his suit coat. Every year there were a few mornings like this one, filled with the promise of bleak skies and blustery winds. Nature making a small joke, causing the tourists on Miami Beach to grumble and walk the sandy stretches in their sweaters. In Little Havana, the older Cuban women would wear heavy woolen overcoats and curse the wind, forgetting that in the summer they carried parasols and cursed the heat. In Liberty City, the rat holes in the crack houses would whistle with cold. The junkies would shiver and struggle with their pipes. But soon enough the city would return to sweaty, sticky normalcy.

One day, he thought as he walked briskly, perhaps two. Then the warm air will freshen out of the South and we will all quickly forget the cold.

Matthew Cowart was a man moving light through life.

Circumstances and bad luck had cut away many of the accoutrements of impending middle age; a simple divorce had sliced away his wife and child, messy death his parents; his friends had slid into a separate existence defined by rising careers, squads of young children, car payments, and mortgages. For a time there had been attempts by some to include him in outings and parties, but, as his solitude had grown, accompanied by his apparent comfort in it, these invitations had fallen off and finally stopped. His social life was defined by an occasional office party and shop talk. He had no lover and felt a vague confusion as to why he didn't. His own apartment was modest, in a sturdy high-rise overlooking the bay, built in the 1950s. He had filled it with old furniture, bookcases stuffed with mystery novels and true crime nonfiction, chipped but utilitarian dinnerware, a few forgettable framed prints hanging on the walls.

Sometimes he thought that when his wife had taken their daughter, all the color had fled from his life. His own needs were satisfied by exercise – an obligatory six miles a day, running through a downtown park, an occasional game of pickup basketball at the YMCA and his job at the newspaper. He felt possessed of a remarkable freedom yet somehow worried that he had so few recognizable debts.

The wind was still gusting hard, pulling and tugging at a trio of flags outside the main entrance to the Miami Journal. He paused momentarily, looking up at the stolid yellow square building. The paper's name was emblazoned in huge red, electric letters against one wall. It was a famous place, well known for its aggressiveness and power. On the other side, the paper looked over the bay. He could see wild waters splashing up against the dock where huge rolls of newsprint were unloaded. Once, while sitting alone in the cafeteria eating a sandwich, he'd spotted a family of manatees cavorting about in the pale blue water, no more than ten yards from the loading dock. Their brown backs burst through the surface, then fell back beneath the waves. He'd looked about for someone to tell but had found no one, and had spent the next few days, at lunch, staring constantly out at the shifting blue-green surface for another glimpse of the animals. It was what he liked about Florida; the state seemed cut from some jungle, which was always threatening to overtake all the development and return it to something primeval. The paper was forever doing stories about twelve-foot alligators getting trapped on entrance ramps to the interstate and stopping traffic. He loved those stories: an ancient beast confronting a modern one.

Cowart moved quickly through the double doors that led to the Journal's newsroom, waving at the receptionist who sat partially hidden behind a telephone console. Next to the entrance was a wall devoted to plaques, citations, and awards: a parade of Pulitzers, Kennedys, Cabots, Pyles, and others with more mundane names. He paused at a bank of mailboxes to pick up his morning mail, flipping rapidly through the usual handouts and dozens of press releases, political statements, and proposals that arrived every day from the congressional delegation, the mayor's office, the county manager's office, and various police agencies, all alerting him to some development that they thought worthy of editorial attention. He sighed, wondering how much money was wasted on all these hopeless efforts. One envelope, however, caught his eye. He separated it from the pile.

It was a thin, white envelope with his name and address written in sturdy block print. There was a return address in the corner, giving a post office box number in Starke, Florida, in the northern portion of the state. The state prison, he thought instantly.

He put it on top of the other letters and headed toward his office, maneuvering amidst the room of desks, nodding at the few reporters who were in early and already working the telephones. He waved at the city editor, who had his feet up on his desk in the center of the room and was reading the last edition. Then he moved through a set of doors in the rear of the newsroom marked EDITORIAL. He was halfway into his cubicle when he heard a voice from nearby.

'Ahh, the young Turk arrives early. What could bring you in before the hordes? Unsettled by the troubles in Beirut? Sleepless over the president's economic recovery program?'

Cowart stuck his head around a partition. 'Morning, Will. Actually, I just wanted to use the WATS line to call my daughter. I'll leave the truly deep and useless worrying to you.'

Will Martin laughed and brushed a forelock of white hair out of his eyes, a motion that belonged more to a child than an old man. 'Go. Abuse the abundant financial generosity of our beloved newspaper. When you get finished, take a look at the story on the Local page. It seems that one of our black-eyed dispensers of justice cut something of a deal for an old buddy caught driving under the influence. It could be time for one of your ever-popular crime-and-punishment crusades.'

'I'll look at it, Cowart said.

'Damn cold this morning,' said Martin. 'What's the point of living down here if you still have to shiver on the way to work? Might as well be Alaska.'

'Why don't we editorialize against the weather? We're always trying to influence the heavens, anyway. Maybe they'll listen to us this time.'

'You've got a point, Martin smiled.

'And you're just the man for the job, Cowart said.

'True, Martin replied. 'Not steeped in sin, like you, I have a much better connection to the Almighty. It helps in this job.'

'That's because you're so much closer to joining him than I.'

His neighbour roared. 'You're an ageist, he protested, waggling a finger. 'Probably a sexist, a racist, a pacifist – all the other ists, too.'

Cowart laughed and headed to his desk, dumping the pile of mail in the middle and leaving the single envelope on top. He reached out for it, while with the other hand he started dialing his ex-wife's number. With any luck, he thought, they should be at breakfast.

He crooked the receiver beneath his shoulder and ear, freeing his hand while the connection was being made. As the telephone began ringing he opened the envelope and took out a single sheet of yellow legal-ruled paper.

Dear Mr. Cowart:

I am currently awaiting execution on Death Row for a crime that I DID NOT COMMIT.

'Hello?'

He put the letter down. 'Hello, Sandy. It's Matt. I just wanted to talk to Becky for a minute. I hope I didn't disturb anything.'

'Hello, Matt.' He heard a hesitation in her voice. 'No, it's just we're getting ready to go. Tom has to be in court early, so he's taking her to school, and…' She paused, then continued, 'No, it's okay. I have a few things I need to talk over with you anyway. But they've got to go, so can you make it quick?'

He closed his eyes and thought how painful it was not to be involved in the routine of his daughter's life. He imagined spilling milk at breakfast, reading books at night, holding her hand when she got sick, admiring the pictures she drew in school. He bit back his disappointment. 'Sure. I just wanted to say hi.'

I'll get her.'

The phone clunked on the table and in the silence that followed, Matthew Cowart looked at the words: I DID NOT COMMIT.

He remembered his wife on the day they'd met, in the newspaper office at the University of Michigan. She'd been small, but her intensity had seemed to contradict her size. She'd been a graphic design student, who worked part-time doing layouts and headlines, poring over page proofs, pushing her dark wavy hair away from her face, concentrating so hard she rarely heard the phone ring or reacted to any of the dirty jokes that flew about in the unbridled newsroom air. She'd been a person of precision and order, with a draftsman's approach to life. The daughter of a Midwestern-city fire captain who'd died in the line of duty, and a grade-school teacher, she craved possessions, longed for comforts. He'd thought her beautiful, was intimidated by her desire, and was surprised when she'd agreed to go on a date with him; surprised further when, after a dozen dates, she'd slept with him.

He'd been the sports editor, which she had thought was a silly waste of time. Over-muscled men in bizarre outfits fighting over variously shaped balls, she would say. He had tried to educate her to the romance of the events, but she had been intransigent. After a while, he had switched to covering real news, throwing himself tenaciously after stories, as their relationship had solidified. He'd loved the endless hours, the pursuit of the story, the seduction of writing. She'd thought he would be famous or, if not famous, important. She'd followed him when he got his first job offer on a small Midwestern paper. A half dozen years later, they'd still been together. On the same day that she announced she was pregnant, he got his offer from the Journal. He was to cover criminal courts. She was to have Becky.

'Daddy?'

'Hi, honey.'

'Hi, Daddy. Mommy says I can only talk for a minute. Got to get to school.'

'Is it cold there, too, honey? You should wear a coat.'

'I will. Tom got me a coat with a pirate on it that's all orange for the Bucs. I'm going to wear that. I got to meet some of the players, too. They were at a picnic where we were helping get money for charity.'

Other books

Sensual Stranger by Tina Donahue

The Book of Books by Melvyn Bragg

MoonlightDrifter by Jessica Coulter Smith

A Cowboy for Christmas by Em Petrova

Fever Claim (The Sigma Menace) by Marie Johnston

Baba Dunja's Last Love by Alina Bronsky, Tim Mohr

The Reluctant by Aila Cline

Gate of the Sun by Elias Khoury

Jacob by Jacquelyn Frank

Commuters by Emily Gray Tedrowe