Joan of Arc: A Life Transfigured (22 page)

Read Joan of Arc: A Life Transfigured Online

Authors: Kathryn Harrison

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Historical, #History, #Europe, #France, #Western

In contrast, Joan would prove as much a demagogue as Jesus, whose radical departure from law to love demanded social justice. A refusal to remain within the confines imposed on gender was a potentially even more disruptive departure from convention than a commitment to embrace the underclass, especially a refusal that was broadcast to

ever more people.

“Whoever listened to the voice and looked into the eyes of Joan of Arc fell under a spell,” Twain explained, “and was not his own man any more.”

“When Joan departed from Blois to go to Orléans,” Pasquerel testified, “the priests marched in front of the army,… singing the

Veni Creator Spiritus

,” a ninth-century Latin hymn (we would recognize it as a Gregorian chant) sung a cappella whether in a chapel or on a military campaign. Its first verse translates “Come, Holy Ghost, Creator blest, and in our hearts take up Thy rest. Come with Thy grace and heavenly aid, to fill the hearts which Thou hast made.” As the vanguard of priests parted the air with sacred song, preparing the way for the promised Virgin from Lorraine, Joan moved before her troops at a more stately pace than she would ever allow them again, through an expanse of moor and forest known as the Sologne. There, Pasquerel remembered, “they camped that [first] night in the fields and did the same on the night following.” As able a horsewoman as Joan was when armored, she was unused to sleeping in armor and, according to her page, Louis de Coutes,

“awoke bruised and weary” and dismissed the pain, which had no place in her vision of the quest on which she’d embarked. It wasn’t, after all, a battle wound, which would prove less easy to deny. Just as the Templars had regarded Jerusalem as a holy city possessed by infidels, so did Joan see Orléans, the city she and her crusaders were to save in the name of God. This was the quest’s picturesque aspect, not consciously choreographed as a romance but informed by the stories Joan knew so well, among them that of Lorraine’s own Baldwin and Godfrey, leaders of the First Crusade, the elder dubbed Baldwin I of Jerusalem for his holy courage, the first among crusaders to bear the title King of Jerusalem.

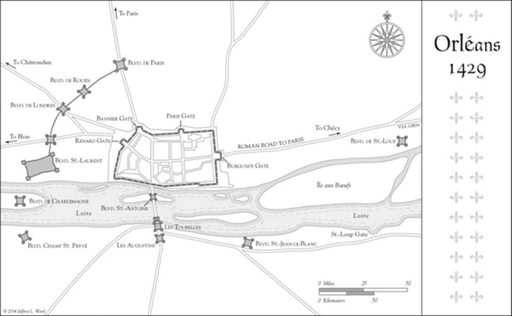

A great marshy basin inadequately drained by the Loire, the Sologne was uninhabited at the time, its population sparse and migratory—a landscape claimed by spies who would have quite a scene to report back to the English. Joan and the convoy emerged from the woods at Chécy, just five miles east of Orléans, where they were met by the famed and noble Bastard of Orléans, Jean, Count of Dunois, who was, as he testified, “in charge of the city, being lieutenant general in the field.” The son of Louis I—Duke of Orléans and Charles

VI’s younger brother—the Bastard of Orléans (

Fig. 15

) would fight alongside Joan at Orléans and for the rest of the Loire campaign, one of only two of her comrades who proved unwaveringly loyal to her to the very end.

Not surprisingly, long before Joan arrived, Dunois had ferreted out all he could about the girl who was coming to win the war he was losing. His envoys

“the lord de Villars, seneschal of Beaucaire, and Jamet du Thillay, who was afterward bailiff of Vermandois,” had returned from Chinon to confirm that whoever she was, she had the Church’s approval and the dauphin’s army, augmented by corps of fanatical followers, a

“rough band of looters and libertines,” according to one source, from which “Joan forged a disciplined army of soldiers.” The count

“immediately collected a great number of soldiers,” Jean d’Aulon testified, “to go out and meet her” and discovered the Maid in command of far more reinforcements and provisions than he had expected. Tethered to a city whose debilitated citizens fixed on one religious cure after another, Dunois had seen them come and go, all of them, flocks of self-scourging, nearly unclothed penitents, wailers and keeners rubbing ash into their wounds, whole monasteries processing through the streets with banners and crucifixes, chanting prayers purchased by those who could afford them. The siege wrung insanity from the city, squeezing zealots out onto the streets until every corner had its own harangue. Naturally, the people of Orléans were fixed on the Maid, but here was evidence of her sway beyond the city’s walls. Not only had the bankrupt dauphin clearly gone further into debt to outfit Joan for battle, but he had also sent her in the company of captains of high rank. Joan’s grip on the whole of France’s imagination was proved by the number of soldiers who enlisted to fight under her command—twenty-five hundred was a large army by medieval measure. Dunois noted that she had convinced a great number of clerics to join her army as well—enough chaplains, Joan informed him, to have confessed every last one of her soldiers. They were ready to fight, and she to allow them to face death.

Between Blois and Orléans, however, were Beaugency and Meung, both occupied by the English, who also controlled all major roads on that (west) side of Orléans. The only reasonable course was to make

a wide berth around the two towns so that they could approach the city from the east, which was less heavily guarded,

“instead of going straight to where Talbot and the English” were, as Joan had assumed.

“Was it you who advised me to come here, on this side of the river?” Joan demanded of Dunois when she discovered in which direction she had unknowingly been led. Her squire, Jean d’Aulon, testified that Dunois answered yes.

“I answered that I and others, who were the wisest, had given that advice in the belief that it was the best and surest.”

Joan had approached Orléans under the assumption that she was off to wage war, leading an army intended to drive off the English, but

“in actual fact it had as its immediate aim the revictualing of the city,” a mission conceived, according to Charles’s counselor, Guillaume Cousinot,

“as a test for Joan.” To deliver a convoy that included, according to Jean Chartier,

“many wagons and carts of grain and a large number of oxen, sheep, cattle, pigs, and other foodstuffs” required a circuitous approach that couldn’t accommodate the thousands of soldiers under Joan’s command. They would have to wait while the convoy crossed the Loire at Chécy, just east of Orléans, as Chécy presented the advantage of unguarded access to the river’s right bank, on which Orléans lay. Here the river was about four hundred yards wide,

“shallow, rapid, but navigable, with many sand banks and islands.” Unfortunately, an unexpected obstacle had presented itself. An adverse wind, blowing east instead of west, now prevented the use of barges to transport provisions to the estimated twenty thousand hungry citizens waiting within the city’s walls. The situation, as Dunois presented it, was beyond mortal control. That was exactly why she had been sent, Joan argued. As Dunois and his captains noted, her assumption that she was being led directly to the enemy—on the other side of the Loire—betrayed a profound lack of understanding of the geography she’d covered.

“In God’s name,” Joan said to all members of the war council that had excluded her, “the counsel of the Lord God is wiser and surer than yours … It is the help of the King of Heaven. It does not come through love for me, but from God himself who, on the petition of Saint Louis and Saint Charlemagne, has had pity on the town of Orléans and has refused to suffer the enemy to have both the body

of the lord of Orléans and his city”—the Duke of Orléans having been captured at Agincourt. As the leader of the Armagnac party, the duke, who was Dunois’s legitimate half brother,

*4

was literally priceless—not offered for ransom—and had been incarcerated across the channel for more than fourteen years. This was the only time Joan was observed to have mentioned Charlemagne or Saint Louis, invoking earthly and immortal powers and conflating kings with saints, a confusion that wasn’t hers alone but inspired by the divine right of kings, which granted the anointed immunity to mortal judgment, thus dangling the temptations of tyranny. Charlemagne, never canonized, reigned as the first Holy Roman emperor from 800 to 814; it was his protection of the papacy that first married church to state. Saint Louis, the only king of France to be canonized, reigned from 1226 until 1270 and led two crusades. A petition to undertake a holy war couldn’t have found a more likely, and ultimately ironic, voice: it was Saint Louis who, in pursuit of the Cathars (who believed the material world was the work of Satan and rejected the Eucharist, arguing that Jesus’s body could not be contained in a piece of bread), established the Inquisition’s power and reach, thus sanctioning an indefinite state of holy war, its first target a sect free from gender bias. Catharism placed no value on one sex over the other; not only did it attract women as converts, but it invited them into the clergy.

“You thought you had deceived me,” Joan said to the captains who had sidelined her, “but it is you who have deceived yourselves, for I am bringing you better help than ever you got from any soldier or any city.”

“Immediately, at that very moment,” Dunois recalled of his initial collision with Joan, “the wind, which had been adverse and had absolutely prevented the ships carrying the provisions for the city of Orléans from putting out, changed and became favorable.” On the river’s bank, the beech saplings’ slender trunks righted themselves and then pitched their limbs to the west. Immediately, the barges were loaded, their sails raised, and the provisions borne across the river. From this

point forward Dunois remained convinced of Joan’s sanctity and the divine source of the aid she brought. “That is the reason why I think that Joan, and all her deeds in war and in battle, were rather God’s work than man’s,” he testified, “the sudden changing of the wind, I mean, after she had spoken.”

Pasquerel’s version was a little different, and no less marvelous: “Now the river was so low that the ships could not ride up or touch the bank where the English were; and suddenly the water rose, so that the ships could touch land on the French side.”

To view a full-size version of this image, click

HERE

.

*1

Chain mail: A modern pleonasm, as both “chain” and “mail” mean the same thing, chain originally indicating mail with a chain-like appearance.

*2

In some versions of the Arthurian legend, Excalibur and the Sword in the Stone are one; in others they are two separate swords.

*3

While Jesus’s relative poverty argues for his not having had the education lavished on boys from more affluent families, two scriptural references suggest he could read. Luke 4:17 tells of Jesus’s reading from the book of the prophet Isaiah in the synagogue of Nazareth. In John 8:6, Jesus “drew in the dirt” to avoid being caught in the Pharisees’ rhetorical trap, interpreted by some as an inability to write, although some versions of the book replace “drew” with “wrote,” and later manuscripts refer to his having written the sins of the Pharisees in the dirt.

*4

Jean Dunois, Count of Dunois (and later Count of Longueville), was the illegitimate son of Prince Louis d’Orléans and his mistress, Mariette d’Enghien.

Even without a magically rising river or fortuitous shift of wind, the convoy’s entry into Orléans proceeded with the unnatural ease of parting seas. “The Maid immediately boarded the boat, and I with her, and the rest of her men turned back toward Blois,” her squire, Jean d’Aulon, testified, “and we entered the city safe and sound with my lord Dunois and his people.”

Joan’s page reported an equally uneventful arrival. “Joan, I, and several others were conveyed across the water to the city side, and from there, we entered Orléans.” To approach the city from the east required passing unimpeded before the bastille of Saint-Loup, occupied by the enemy, before which was the boulevard of Saint-Loup. In this context the word “boulevard” means not a road but a bulwark

*1

intended to provide cover from gunpowder artillery. Constructed of earth and wood, the boulevard’s walls were both low enough to fire over easily and yielding enough to absorb cannon strikes without breaking or crumbling like the stone walls they protected. The French had used them for about twenty-five years—for as long as they’d had bombards—and the English, seeing their effectiveness, adopted the practice. As Dunois had sent most of Joan’s army and all the clergy except Pasquerel back to Blois, the provisions traveled under a minimal guard of about two hundred soldiers in expectation of minimal interference. There was no hope of transporting so much food stealthily, or any more quickly than an ox moved.