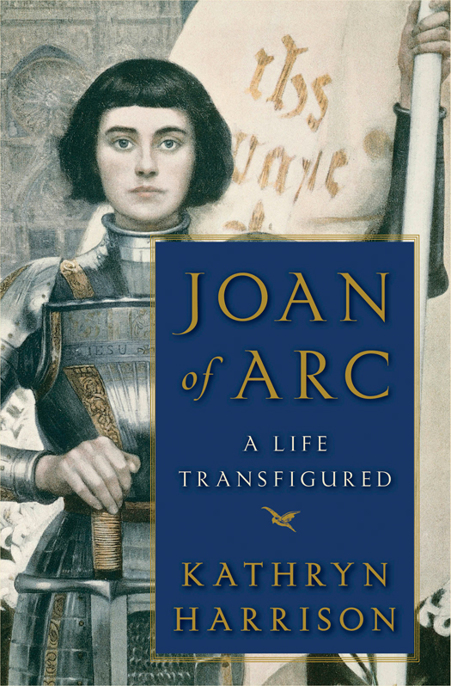

Joan of Arc: A Life Transfigured

Read Joan of Arc: A Life Transfigured Online

Authors: Kathryn Harrison

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Historical, #History, #Europe, #France, #Western

A

LSO BY

K

ATHRYN

H

ARRISON

Fiction

Thicker Than Water

Exposure

Poison

The Binding Chair

The Seal Wife

Envy

Enchantments

Nonfiction

The Kiss: A Memoir

Seeking Rapture: Scenes from a Woman’s Life

The Road to Santiago

Saint Thérèse of Lisieux

The Mother Knot: A Memoir

While They Slept: An Inquiry into the Murder of a Family

Copyright © 2014 by Kathryn Harrison

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Doubleday, a division of Random House LLC, New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto, Penguin Random House companies.

DOUBLEDAY and the portrayal of an anchor with a dolphin are registered trademarks of Random House LLC.

Maps designed by Jeffrey L. Ward

Jacket design by John Fontana

Jacket image of Joan of Arc: engraving from

Figaro Illustre

magazine, 1903

© DEA/M. SEEMULLER/Getty Images

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Harrison, Kathryn.

Joan of Arc : a life transfigured / Kathryn Harrison.—First edition.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-0-385-53120-7 (hardcover)—ISBN 978-0-385-53122-1 (eBook)

1. Joan, of Arc, Saint, 1412–1431. 2. France—History—Charles VII,

1422–1461. 3. Christian saints—France—Biography. I. Title.

DC103.H25 2014

944’.026092—dc23

[B] 2014005921

v3.1

For Gerry Howard

I used to be a hen,

but I loved an angel and became a peacock.

N

IKOS

K

AZANTZAKIS

Contents

Cover

Other Books by This Author

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

CHAPTER I

In the Beginning Was the Word

CHAPTER II

By Angels’ Speech and Tongue

CHAPTER III

A Small, Nay, the Least, Thing

CHAPTER IV

The King’s Treasure

CHAPTER V

Who Is This Then, That Wind and Seas Obey?

CHAPTER VI

Surrender to the Maid

CHAPTER VII

A Leaping Stag

CHAPTER VIII

Black Horseman

CHAPTER IX

The Golden Cloak

CHAPTER X

The Tower Keep

CHAPTER XI

A Heart That Would Not Burn

CHAPTER XII

Life Everlasting

Chronology

Acknowledgments

Notes

Bibliography

Illustration Credits

About the Author

Illustrations

“Have you not heard the prophecy that France was to be ruined by a woman and restored by a virgin from the marshes of Lorraine?”

By the time Joan of Arc proclaimed herself La Pucelle, the virgin sent by God to deliver France from its enemies, the English, she had been obeying the counsel of angels for five years. The voices Joan heard, speaking from over her right shoulder and accompanied by a great light, had been hers alone, a rapturous secret. But when, in 1429, they announced that the time had come for Joan to undertake the quest for which they had been preparing her, they transformed a seemingly undistinguished peasant girl into a visionary heroine who defied every limitation placed on a woman of the late Middle Ages.

Expected by those who raised her to assume nothing more than the workaday cloak of a provincial female, Joan told her family nothing of what her voices asked, lest her parents try to prevent her from fulfilling what she embraced as her destiny: foretold, ordained, inescapable. Seventeen years old, Joan dressed herself in male attire at the command of her heavenly father. She sheared off her hair, put on armor, and took up the sword her angels provided. She was frightened of the enormity of what God had asked of her, and she was feverish in her determination to succeed at what was by anyone’s measure a preposterous mission.

As Joan protested to her voices, she “knew not how to ride or lead in war,” and yet she roused an exhausted, under-equipped, and impotent army into a fervor that carried it from one unlikely victory to the next. In fact, outside her unshakable faith—or because of that

faith—Joan of Arc was characterized above all by paradox. An illiterate peasant’s daughter from the hinterlands, Joan moved purposefully among nobles, bishops, and royalty, unimpressed by mortal measures of authority. She had a battle cry that drove her legions forward into the fray; her voice was described as gentle, womanly. So intent on vanquishing the enemy that she threatened her own men with violence, promising to cut off the head of any who should fail to heed her command, she recoiled at the idea of taking a life, and to avoid having to use her sword, she led her army carrying a twelve-foot banner that depicted Christ sitting in judgment, holding the world in his right hand, and flanked by angels. In the aftermath of combat, Joan didn’t celebrate victory but mourned the casualties; her men remembered her on her knees weeping as she held the head of a dying enemy soldier, urging him to confess his sins.

A mortal whose blood flowed red and real from battle wounds, she had eyes that beheld angels, winged and crowned. When she fell to her knees to embrace their legs, she felt their flesh solid in her arms. Her courage outstripped that of seasoned men-at-arms; her tears flowed as readily as did any other teenage girl’s. Not only a virgin, but also an ascetic who held herself beyond the reach of sensual pleasure, she wept in shock and rage when an English captain called her a whore. Yet, living as a warrior among warriors, she betrayed no prudery when time came to bivouac, undressing and sleeping among lustful young knights who remembered the beauty of a body none dared approach—not even after Joan chased off any prostitute foolish enough to tramp after an army whose leader’s claim to power was indivisible from her chastity. Under the exigencies of warfare, she didn’t allow her men the small sin of blasphemy; coveting victory above all else, she righteously seized an advantage falling on a holy day. She knew God’s wishes; she followed his direction; she questioned nothing. Her quest, revealed to her alone, allowed her privileges no pope would claim. On trial for her life and unfamiliar with the fine points of Catholic doctrine, she nimbly sidestepped the rhetorical traps of Sorbonne-trained doctors of the Church bent on proving her a witch and a heretic. The least likely of commanding officers, she changed the course of the Hundred Years War, and that of history.

The life of Joan of Arc is as impossible as that of only one other,

who also heard God speak: Jesus of Nazareth, prince of paradox as much as peace, a god who suffered and died a mortal, a prophet whose parables were intended to confound, that those who

“seeing may not see, and hearing may not understand,” a messenger of forgiveness and love who came bearing a sword, inspiring millennia of judgment and violence—the blood of his

“new and everlasting covenant” extracted from those who refused his heavenly rule. More than that of any other Catholic martyr, Joan of Arc’s career aligns with Christ’s, hers

“the most noble life that was ever born into this world save only One,” Mark Twain wrote. Her birth was prophesied: a virgin warrior would arise to save her people. She had power over the natural world, not walking on water, but commanding the direction of the wind. She foretold the future. If she wasn’t transfigured while preaching on a mount, she was, eyewitnesses said, luminous in battle, light not flaring off her armor so much as radiating from the girl within. The English spoke of a cloud of white butterflies unfurling from her banner—proof of sorcery, they called it. Her touch raised the dead. Her feats, which continue six centuries after her birth to frustrate ever more modern and enlightened efforts to rationalize and reduce to human proportions, won the allegiance of tens of wonder-struck thousands and made her as many ardent enemies. The single thing she feared, she said, was treachery.

Captured, Joan was sold to the English and abandoned to her fate by the king to whom she had delivered the French crown. Her passion unfolded in a prison cell rather than a garden, but like Jesus she suffered lonely agonies. Tried by dozens of mostly corrupt clerics, Joan refused to satisfy the ultimatums of Church doctors who demanded she abjure the God she knew and renounce the voices that guided her as the devil’s deceit. When she would not, she was condemned to death and burned as a heretic, the stake to which she was bound raised above throngs of jeering onlookers curious to see what fire might do to a witch. She was only nineteen, and her charred body was displayed for anyone who cared to examine it. Had she been a man after all, and if she were, did it explain any of what she’d accomplished?

A sophisticated few of Joan of Arc’s contemporaries might have understood the idea of salvation at the hands of a virgin from the marshes of Lorraine as a communal prayer—more a wish for rescue

than a prophecy. Probably, most took the idea at face value, some giving it credence, others dismissing it. But only one, a girl who claimed she knew little beyond what she’d learned spinning and sewing and taking her turn to watch over the villagers’ livestock, heard it as a vocation. The self-proclaimed agent of God’s will, Joan of Arc wasn’t immortalized so much as she entered the collective imagination as a living myth, exalted by the angelic company she kept and the powers with which it endowed her.

The woman who “ruined” France was Isabeau of Bavaria, a ruination accomplished by disinheriting her son the dauphin Charles, to whom Joan would restore France’s throne, and allowing his paternity to be called into question. It was a credible doubt that might have been cast on any of Isabeau’s eight children, as she was notoriously unfaithful to her husband, the mad (we would call him schizophrenic) Charles VI. Bastardy, though it invited dynastic squabbles among opposing crowns with shared ancestry, wasn’t a cause for shame among the nobility but was announced if not advertised, a

brisure

, or “bar sinister,” added to the coat of arms worn by sons conceived outside a family patriarch’s official marriage.

*1

In fact, it was an illustrious bastard’s invasion of England in 1066 that precipitated the centuries of turf wars between the French and the English. As Duke of Normandy, William the Conqueror claimed England’s throne for his own but remained a vassal of the French king, as did those who ruled after him. The arrangement guaranteed centuries of dynastic turmoil, and the house of Valois

*2

had the misfortune of presiding over the Hundred Years War, at the beginning of which France had everything to lose. Centuries of crusades following the Norman conquests had established the livre as the currency of international trade, and

France’s wealth purchased its preeminence among nations. French was not used for purposes of haggling alone but was the lingua franca of Europe, the language in which Marco Polo’s

Travels

was published.